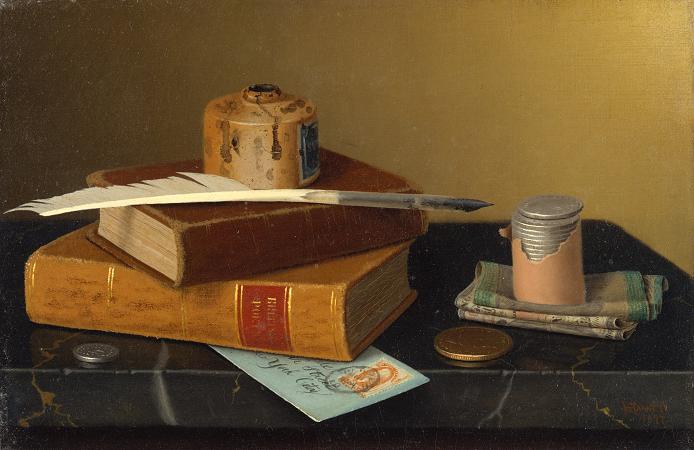

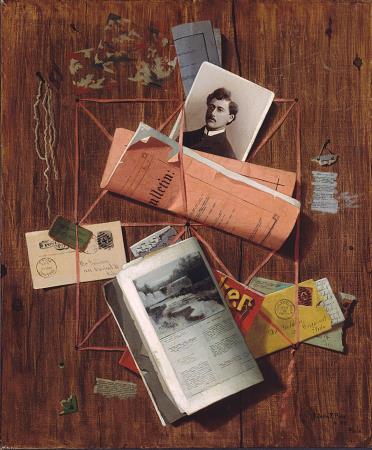

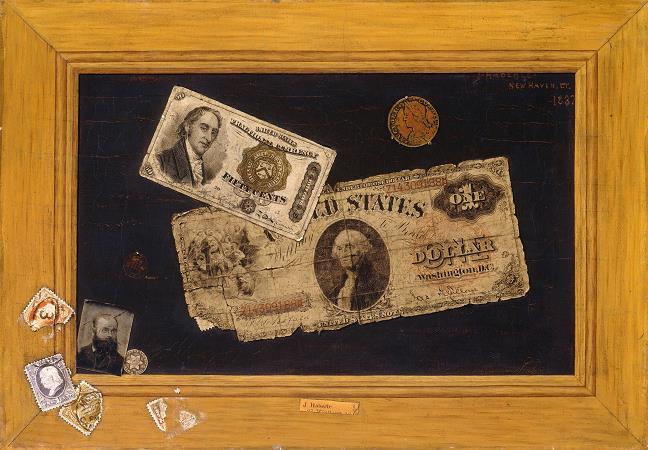

Trompe l'oeil. Trompe-l'oeil is an art technique that uses realistic imagery to create the optical illusion that the depicted objects exist in three dimensions. Forced perspective is a comparable illusion in architecture. The phrase, which can also be spelled without the hyphen and ligature in English as trompe l'oeil, originates with the artist Louis-Léopold Boilly, who used it as the title of a painting he exhibited in the Paris Salon of 1800. Although the term gained currency only in the early 19th century, the illusionistic technique associated with trompe-l'oeil dates much further back. It was often employed in murals. Instances from Greek and Roman times are known, for instance in Pompeii. A typical trompe-l'oeil mural might depict a window, door, or hallway, intended to suggest a larger room. A version of an oft-told ancient Greek story concerns a contest between two renowned painters. Zeuxis produced a still life painting so convincing that birds flew down to peck at the painted grapes. A rival, Parrhasius, asked Zeuxis to judge one of his paintings that was behind a pair of tattered curtains in his study. Parrhasius asked Zeuxis to pull back the curtains, but when Zeuxis tried, he could not, as the curtains were included in Parrhasius's painting—making Parrhasius the winner. A fascination with perspective drawing arose during the Renaissance. Many Italian painters of the late Quattrocento, such as Andrea Mantegna and Melozzo da Forli, began painting illusionistic ceiling paintings, generally in fresco, that employed perspective and techniques such as foreshortening to create the impression of greater space for the viewer below. This type of trompe l'oeil illusionism as specifically applied to ceiling paintings is known as di sotto in sù, meaning "from below, upward" in Italian. The elements above the viewer are rendered as if viewed from true vanishing point perspective. Well-known examples are the Camera degli Sposi in Mantua and Antonio da Correggio's Assumption of the Virgin in the Parma Cathedral. Similarly, Vittorio Carpaccio and Jacopo de' Barbari added small trompe l'oeil features to their paintings, playfully exploring the boundary between image and reality. For example, a fly might appear to be sitting on the painting's frame, or a curtain might appear to partly conceal the painting, a piece of paper might appear to be attached to a board, or a person might appear to be climbing out of the painting altogether—all in reference to the contest of Zeuxis and Parrhasius. In a 1964 seminar, the psychoanalyst and theorist Jacques Lacan observed that the myth of the two painters reveals an interesting aspect of human cognition. While animals are attracted to superficial appearances, humans are enticed by the idea of things that are hidden. Perspective theories in the 17th century allowed a more fully integrated approach to architectural illusion, which when used by painters to "open up" the space of a wall or ceiling is known as quadratura. Examples include Pietro da Cortona's Allegory of Divine Providence in the Palazzo Barberini and Andrea Pozzo's Apotheosis of St Ignatius on the ceiling of the Roman church of Sant'Ignazio. The Mannerist and Baroque style interiors of Jesuit churches in the 16th and 17th centuries often included such trompe-l'oeil ceiling paintings, which optically open the ceiling or dome to the heavens with a depiction of Jesus', Mary's, or a saint's ascension or assumption. An example of a perfect architectural trompe-l'oeil is the illusionistic dome in the Jesuit church, Vienna, by Andrea Pozzo, which is only slightly curved, but gives the impression of true architecture. Trompe-l'oeil paintings became very popular in Flemish and later in Dutch painting in the 17th century arising from the development of still life painting. The Flemish painter Cornelis Norbertus Gysbrechts created a chantourné painting showing an easel holding a painting. Chantourné literally means cutout and refers to a trompe l'oeil representation designed to stand away from a wall.

more...