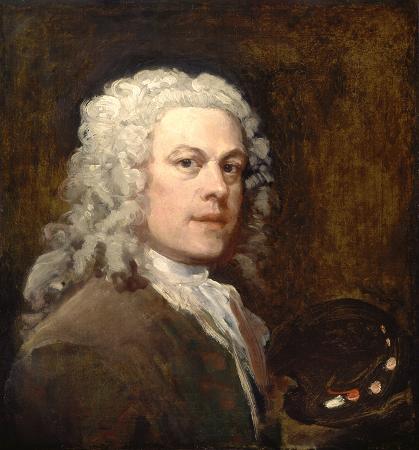

Judith Leyster Self Portrait (c1630). Oil on panel. 75 x 65. Self-portrait by Judith Leyster is an Dutch Golden Age painting in oils in the collection of the National Gallery of Art that was offered in 1633 as a masterpiece to the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke. It was attributed for centuries to Frans Hals and was only properly attributed to Judith Leyster upon acquisition by the museum in 1949. The style is indeed comparable to that of Hals, Haarlem's most famous portraitist. In 2016 a second self-portrait was found, dating from around 1653. Though Leyster looks very relaxed, the composition is to some extent an artificial confection. She is dressed in what must have been her best clothes, which in reality she is unlikely to have risked near wet oil paint, and the figure she is painting is borrowed from a different work, and was perhaps never actually painted as a single figure. Critics have found a sense of Baroque closeness in this painting. The artist and the viewer are very close in space. Many of the elements in the painting are foreshortened in order to feel closer and like they are coming into the viewer's space. For women during this time, being a painter was unusual. Judith Leyster, however, was a working artist at the age of eighteen. She became the first successful woman painter in the Netherlands during the height of Dutch art, known as the Dutch Golden Age. She taught students while running her own workshop and selling her works. Leyster specialized in genre scenes, along with portraits and still lives. She would sign her paintings with a star because her last name translated to leading star. Judith Leyster was also the first woman member of the Haarlem painters' guild which was dominated by men. Unfortunately after her death, her artistic reputation became nonexistent and this painting was misattributed to Frans Hals. It is unclear whether or not Leyster was a student of Frans Hals, but her style did share characteristics with his. This explains why some of her paintings were misattributed to him. The influence of Caravaggio, playing with dramatic contrasts between light and shadow, is seen in many of her works. The illusion of illumination along with soft, broad brushstrokes were shared by both Leyster and Hals. Both of their works included light, airy brushstrokes and same subject matter. Judith Leyster's work had been forgotten after she had died which led to the misattribution to Frans Hals. Because she did not sign many paintings, art historians would misattribute those to Frans Hals or other male Dutch painters during that time. Her Self-Portrait, was supposed to be executed in the 1620s by Hals and may have been among those sold as Daughter of the artist in early sales catalogs. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, collectors and dealers often forged Frans Hals's signature on her paintings and covered up hers. The painting was sold by the Ehrich Galleries of New York on 9 May 1929 to Mr. and Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, of Washington, D.C for 250,000 dollars. In 1928 W.R. Valentiner declared it a portrait of Leyster by Hals. In 1930 Gerrit David Gratama asserted that the painting ws by Leyster herself, declaring that it was done while she was making a study of her painting, The Merry Trio. Judith Leyster entered into the Saint Luke's Guild of Haarlem as an independent master in 1633. This was rare, since women were excluded from joining the guild. Being a part of the guild was extremely important to be successful. It was extremely hard to sell artworks or have a studio where one can teach unless a part of this guild. Leyster even became a master in the guild. It was at the time she was applying to be a master that she created this painting as her masterpiece. In this painting she is showing off her skills. She painted herself in a huge lace collar and silk sleeves which would have been extremely expensive and probably her best clothese. It is unlikely that she ever actually painted wearing these. Like most sitters for portraits, she wanted to be shown at her best. They also allowed her to show off her skill at depicting the different textiles. On the easel there is a laughing fiddler in progress, a typical example of the sort of genre painting subject she mostly painted. Continuing in the tradition of sixteenth-century artists who pushed to have painting seen as a profession as opposed to a craft, Leyster chose to depict herself wearing lace cuffs, rich fabric and a huge collar, which would not have been suitable for painting, but instead draw attention to her wealth and success. She also portrayed raw paint on her palette. This demonstrates her skill as an artist because she carefully placed painted raw paint on her palette. In doing this, she both distinguished herself from less skilled artisans and showcased her technical abilities.

more...