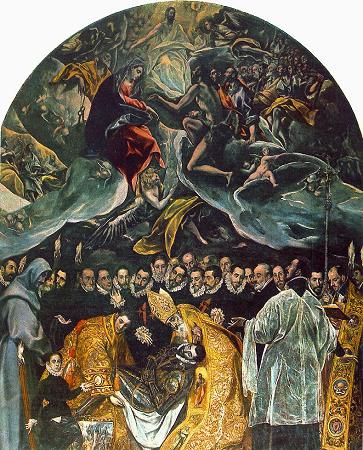

Burial of Count Orgaz (1586). Oil on canvas. 460 x 360. Santo Tome, Toledo, Spain. The Burial of the Count of Orgaz is a 1586 painting by El Greco, a prominent Renaissance painter, sculptor, and architect of Greek origin. Widely considered among his finest works, it illustrates a popular local legend of his time. An exceptionally large painting, it is divided into two sections, heavenly above and terrestrial below, but it gives little impression of duality, since the upper and lower sections are brought together compositionally. The painting has been lauded by art scholars, characterized, inter alia, as one of the most truthful pages in the history of Spain, as a masterpiece of Western Art and of late Mannerism, and as the epitome of Greco's artistic style. The theme of the painting is inspired by a legend of the beginning of the 14th century. In 1312, a certain Don Gonzalo Ruiz de Toledo, mayor of the town of Orgaz, died. Don Gonzalo Ruiz de Toledo was a descendant of the noble Palaiologos family, which produced the last ruling dynasty of the Byzantine Empire. A pious Caballero, the Count of Orgaz was also a philanthropist, who, among other charitable acts, left a sum of money for the enlargement and adornment of the church of Santo Tome, where he wanted to be buried. According to the legend, at the time the Count was murdered, Saint Stephen and Saint Augustine descended in person from the heavens and buried him by their own hands in front of the dazzled Mercedes of those present. The event is depicted in the painting, with every detail of the work's subject described in the contract signed between Greco and the Church. The miracle is also mentioned in the Latin epitaphian inscription, set into the wall below the painting. Although Greco abided by the terms of the contract, he introduced some elements which modernized the legend, such as a series of features attributed to a 16th century customary funeral procession, the vestments of the two saints, as well as the depiction of eminent Toledan figures of his time. The modernization of the legend serves the didactic purpose of the painting, which, in accord with the Counter-Reformation doctrines, stresses the importance of both the veneration of saints and of good deeds for the salvation of the soul. The painting was commissioned by Andres Nunez, the parish priest of Santo Tome, for the side-chapel of the Virgin of the church of Santo Tome. Nunez, who had initiated a project to refurbish the Count's burial chapel, is portrayed in the painting reading. The painting's commission was the last step in the priest's plan to glorify the parish. Signed on 18 March 1586, the contract between Nunez and El Greco laid down specific iconographic demands, stipulated that the artist would pay for the materials, and provided for the delivery of the work until Christmas 1587. Greco must have worked at a frantic pace, and finished the painting between late 1587 and the spring of 1588. A long debate between the priests and the painter followed in relation to the value of the latter's work, for which the contract stipulated that it would be determined by appraisal. Initially intransigent, Greco eventually compromised and settled for the lower first expert estimate, agreeing to receive 13,200 reales. Already in 1588, people were flocking to Santo Tome to see the painting. This immediate popular reception was mainly due to the realistic portrayal of the notable men of Toledo of the time. It was the custom for the eminent and noble men of the town to assist the burial of the noble-born, and it was stipulated in the contract that the scene should be represented in this manner. El Greco would pay homage to the aristocracy of the spirit, the clergy, the jurists, the poets and the scholars, who honored him and his art with their esteem, by immortalizing them in the painting. The Burial of the Count of Orgaz has been admired not only for its art, but also because it is a gallery of portraits of some of the most important personalities of that time in Toledo. In 1612, Francisco de Pisa wrote: The people of our city never grow tired, because there are realistic portraits of many notable men of our times. According to the terms stipulated in the contract and the prevailing scholarly approach, the painting is divided into two zones, juxtaposing the earthly with the heavenly world, which are brought together compositionally. Franz Philipp emphasizes on the element of the assumption of the soul, and argues that the work should be considered as tripartite: the central division of the painting is occupied by the assumptio animae, in the form of a newborn, ethereal baby. Augustine's perception of the soul and its ascent, which evolved from a Neoplatonic basis, is a possible inspiration for the painter's imagery of assumptio animae.

more...