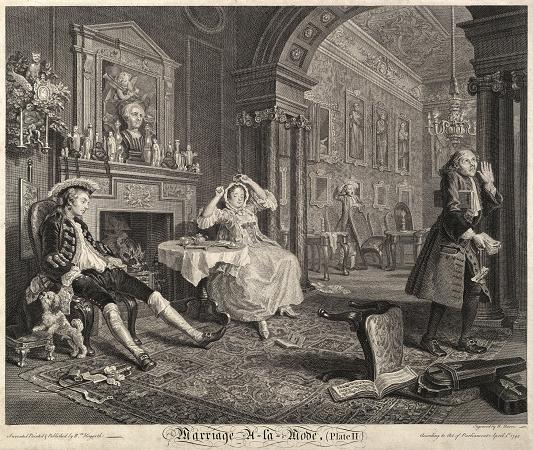

Private Conversation (c1743). Oil on canvas. 70 x 91. The Tête à Tête is the second canvas in the series of six satirical paintings known as Marriage à-la-mode, painted by William Hogarth. The painting is the sparsest in terms of characters present, with only 4: The Viscount, seated, on the right. The Viscountess, seated, across from her husband. The Methodist servant-walking out. The other servant-in the other room. The exact details are not always settled upon, but the primary implication is clear: The two are totally uninterested in each other, and the marriage and the household are rapidly becoming untenable. The clock on the right shows the time as 12:20. Commentators are undecided whether this is late at night or the afternoon but in either case, the implications are damning: If it's 12:20 in the morning, the house has clearly been the scene of a wild and debauched party; the Viscount has been out until all hours and neither are interested in each other. If 12:20 in the afternoon, whatever occurred the night before hasn't been cleaned up, the servants are just waking up, the candles were left burning all night and into the day, and the couple has only recently risen. The husband looks bored, dishevelled and distracted, and has returned exhausted from what was likely a trip to a brothel: the dog has sniffed out what appears to be a lady's nightcap in his master's jacket pocket. The patch on the man's neck indicates that he has contracted a sexually-transmitted disease {in the first painting of the series he is already wearing the patch-before his marriage}. Lying by the husband's feet is his sword, undrawn from its scabbard but broken, alluding to his impotence. The husband's likeness is said to be based upon Hogath's friend, Francis Hayman. The wife has spent the evening at home playing cards. At her feet is a book entitled Hoyle on Whist, and there is an abandoned pack of cards strewn on the floor to her left. In contrast to her husband, the wife looks content and pleased with herself as she takes a satisfied stretch. She sits in an un-ladylike pose with her legs wide apart, and has a large and strategically placed damp patch on the front of her skirt implying she has recently had sex. She is slyly looking to the right through half closed eyes and holding a pocket-mirror above her head-she seems to be signalling to someone, perhaps her lover, out of the picture. There is therefore a deliberate contrast between the unhappy impotent husband who has visited a brothel but was unable to perform and the contented wife who has recently had adulterous sex. The steward is dressed in the style of a pious Methodist and has a book on Regeneration in his coat pocket. Behind his ear is a quill-pen. His entire expression is one of disgust and repudiation. His ledger, together with a clutch of unpaid bills in his hand, are contrasted with a lone receipt on the spike, showing that the Viscount is, like his father the Earl, a spendthrift. The steward is said to be based upon Edward Swallow, butler to Thomas Herring, the then Archbishop of York. The carpet behind the steward has been cut and rolled back to fit around the base of the column, an example of a lack of foresight and planning. The interior is in the neo-Palladian style which Hogarth despised and thought degenerate, and often made the butt of his satire. Ironically, the interior is said to be based upon the drawing-room of 5 Arlington Street, London, the home of Horace Walpole, a great admirer of Hogarth. {The interior also echos the bizarre exterior of the Neo-Palladian style of the earl's new house seen in the first painting of the series The Marriage Settlement-perhaps the interior of the new House?}. The fireplace especially alludes to the deteriorating state of the marriage. The fireplace is, again, in the neo-Palladian style. On the mantelpiece are a mismatched jumble of Indian figurines, glass jars, statuettes and other ornaments. The Roman bust has a broken nose, signifying impotence. The painting above the fireplace is of Cupid, set amongst ruins, playing the bag-pipes and with no string to his bow, all alluding to the discordant and defective state of the marriage. The clock to the right of the fireplace is a grotesque and ridiculous pastiche of Chinoiserie and Rococo-a bush containing a Buddha holding two candlesticks and a ridiculously inappropriate fish and a meowing cat-that is deliberately out of style with the rest of the architecture. Hogarth would have felt it ridiculous to combine neo-Palladian style, which originated in Italy, with Rococo, which originated in France.

more...