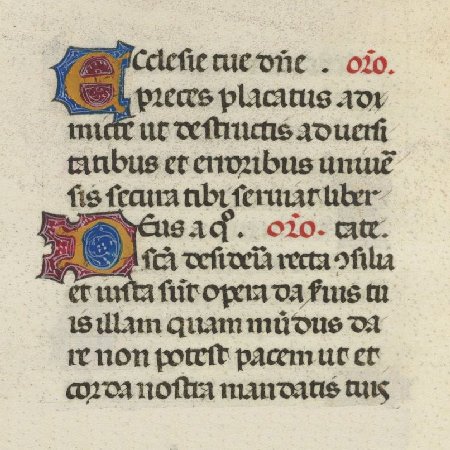

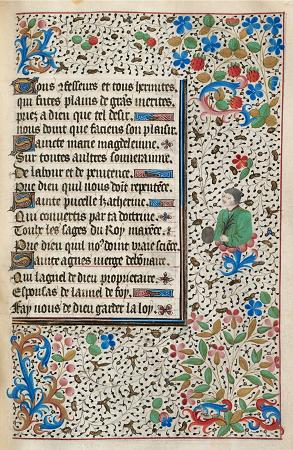

Book of Hours. The book of hours is a Christian devotional book popular in the Middle Ages. It is the most common type of surviving medieval illuminated manuscript. Like every manuscript, each manuscript book of hours is unique in one way or another, but most contain a similar collection of texts, prayers and psalms, often with appropriate decorations, for Christian devotion. Illumination or decoration is minimal in many examples, often restricted to decorated capital letters at the start of psalms and other prayers, but books made for wealthy patrons may be extremely lavish, with full-page miniatures. Books of hours were usually written in Latin, although there are many entirely or partially written in vernacular European languages, especially Dutch. The English term primer is usually now reserved for those books written in English. Tens of thousands of books of hours have survived to the present day, in libraries and private collections throughout the world. The typical book of hours is an abbreviated form of the breviary which contained the Divine Office recited in monasteries. It was developed for lay people who wished to incorporate elements of monasticism into their devotional life. Reciting the hours typically centered upon the reading of a number of psalms and other prayers. A typical example contains the Calendar of Church feasts, extracts from the Four Gospels, the Mass readings for major feasts, the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the fifteen Psalms of Degrees, the seven Penitential Psalms, a Litany of Saints, an Office for the Dead and the Hours of the Cross. Most 15th-century books of hours have these basic contents. The Marian prayers Obsecro te and O Intemerata were frequently added, as were devotions for use at Mass, and meditations on the Passion of Christ, among other optional texts. The book of hours has its ultimate origin in the Psalter, which monks and nuns were required to recite. By the 12th century this had developed into the breviary, with weekly cycles of psalms, prayers, hymns, antiphons, and readings which changed with the liturgical season. Eventually a selection of texts was produced in much shorter volumes and came to be called a book of hours. During the latter part of the thirteenth century the Book of Hours became popular as a personal prayer book for men and women who led secular lives. It consisted of a selection of prayers, psalms, hymns and lessons based on the liturgy of the clergy. Each book was unique in its content though all included the Hours of the Virgin Mary, devotions to be made during the eight canonical hours of the day, the reasoning behind the name Book of Hours. Many books of hours were made for women. There is some evidence that they were sometimes given as a wedding present from a husband to his bride. Frequently they were passed down through the family, as recorded in wills. Although the most heavily illuminated books of hours were enormously expensive, a small book with little or no illumination was affordable much more widely, and increasingly so during the 15th century. The earliest surviving English example was apparently written for a laywoman living in or near Oxford in about 1240. It is smaller than a modern paperback but heavily illuminated with major initials, but no full-page miniatures. By the 15th century, there are also examples of servants owning their own Books of Hours. In a court case from 1500, a pauper woman is accused of stealing a domestic servant's prayerbook. Very rarely the books included prayers specifically composed for their owners, but more often the texts are adapted to their tastes or sex, including the inclusion of their names in prayers. Some include images depicting their owners, and some their coats of arms. These, together with the choice of saints commemorated in the calendar and suffrages, are the main clues for the identity of the first owner. Eamon Duffy explains how these books reflected the person who commissioned them. He claims that the personal character of these books was often signaled by the inclusion of prayers specially composed or adapted for their owners. Furthermore, he states that as many as half the surviving manuscript Books of Hours have annotations, marginalia or additions of some sort. Such additions might amount to no more than the insertion of some regional or personal patron saint in the standardized calendar, but they often include devotional material added by the owner. Owners could write in specific dates important to them, notes on the months where things happened that they wished to remember, and even the images found within these books would be personalized to the owners-such as localized saints and local festivities.

more...