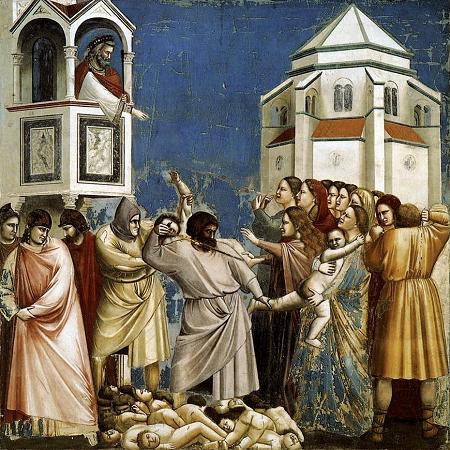

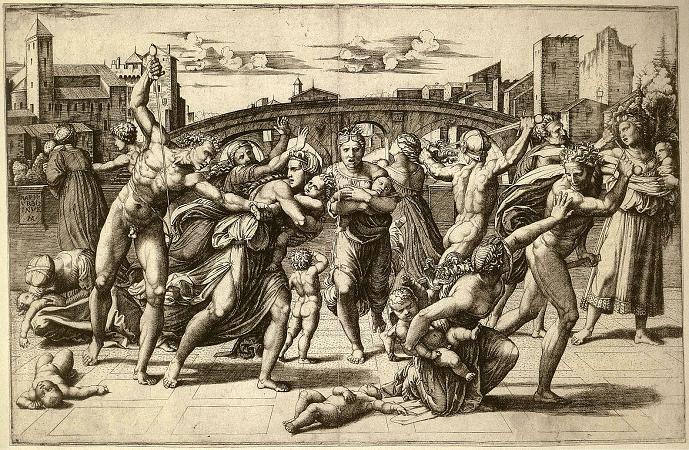

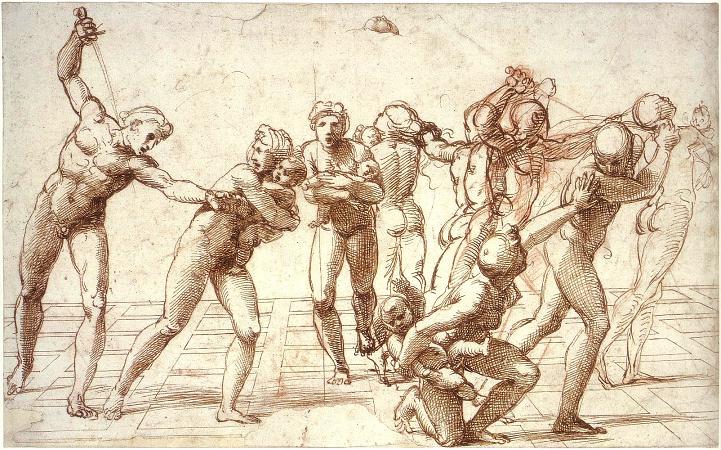

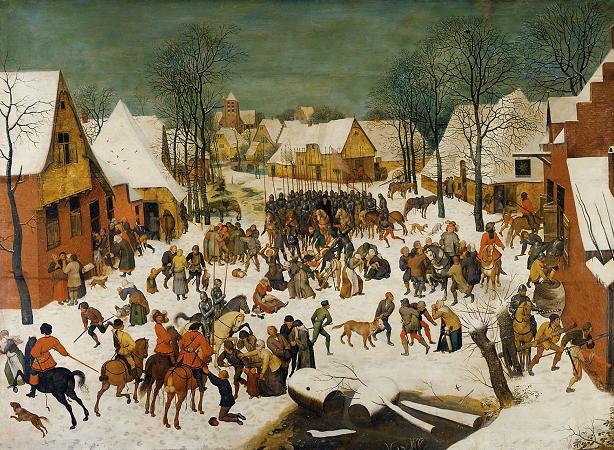

Massacre of Innocents. In the New Testament, the Massacre of the Innocents is the incident in the nativity narrative of the Gospel of Matthew in which Herod the Great, king of Judea, orders the execution of all male children two years old and under in the vicinity of Bethlehem. A majority of Herod biographers, and robably a majority of biblical scholars, hold the event to be myth or folklore. The Catholic Church has claimed the children murdered in Jesus's stead as the first Christian martyrs, and their feast; Holy Innocents Day; is celebrated on 28 December. Matthew's story is found in no other gospel, and the Jewish historian Josephus does not mention it in his Antiquities of the Jews, which records many of Herod's misdeeds including the murder of three of his own sons. Most modern biographers of Herod dismiss the story as an invention. Classical historian Michael Grant, for instance, statedThe tale is not history but myth or folk-lore. It appears to be modeled on Pharaoh's attempt to kill the Israelite children, and more specifically on various elaborations of the original story that had become current in the 1st century. In that expanded story, Pharaoh kills the Hebrew children after his scribes warn him of the impending birth of the threat to his crown, but Moses's father and mother are warned in a dream that the child's life is in danger and act to save him. Later in life, after Moses has to flee, like Jesus, he returns only when those who sought his death are themselves dead. The story of the massacre of the innocents thus plays a part in Matthew's wider nativity story, in which the proclamation of the coming of the Messiah is followed by his rejection by the Jews and acceptance by the gentiles. The relevance of Jeremiah 31:15 to the massacre in Bethlehem is not immediately apparent, as Jeremiah's next verses go on to speak of hope and restoration. Some scholars argue for the historicity of the event. R. T. France acknowledges that the story is similar to that of Moses, but argues t is clear that this scriptural model has been important in Matthew's telling of the story of Jesus, but not so clear that it would have given rise to this narrative without historical basis. France nevertheless notes that the massacre isperhaps the aspect most often rejected as legendary. Some scholars, such as Everett Ferguson, write that the story makes sense in the context of Herod's reign of terror in the last few years of his rule, and the number of infants in Bethlehem that would have been killed; no more than a dozen or so; may have been too insignificant to be recorded by Josephus, who could not be aware of every incident far in the past when he wrote it. The story's first appearance in any source other than the Gospel of Matthew is in the apocryphal Protoevangelium of James of c., which excludes the Flight into Egypt and switches the attention of the story to the infant John the Baptist: And when Herod knew that he had been mocked by the Magi, in a rage he sent murderers, saying to them: Slay the children from two years old and under. And Mary, having heard that the children were being killed, was afraid, and took the infant and swaddled Him, and put Him into an ox-stall. And Elizabeth, having heard that they were searching for John, took him and went up into the hill-country, and kept looking where to conceal him. And there was no place of concealment. And Elizabeth, groaning with a loud voice, says: O mountain of God, receive mother and child. And immediately the mountain was cleft, and received her. And a light shone about them, for an angel of the Lord was with them, watching over them. The first non-Christian reference to the massacre is recorded four centuries later by Macrobius, who writes in his Saturnalia: When he heard that among the boys in Syria under two years old whom Herod, king of the Jews, had ordered killed, his own son was also killed, he said: it is better to be Herod's pig, than his son. The story assumed an important place in later Christian tradition; Byzantine liturgy estimated 14,000 Holy Innocents while an early Syrian list of saints stated the number at 64,000. Coptic sources raise the number to 144,000 and place the event on 29 December. Taking the narrative literally and judging from the estimated population of Bethlehem, the Catholic Encyclopedia more soberly suggested that these numbers were inflated, and that probably only between six and twenty children were killed in the town, with a dozen or so more in the surrounding areas. According to Jewish extra-Biblical traditions, king Nimrod saw a sign in the skies predicting the birth of Abraham, and ordered the slaughter of infant children to avoid it.

more...