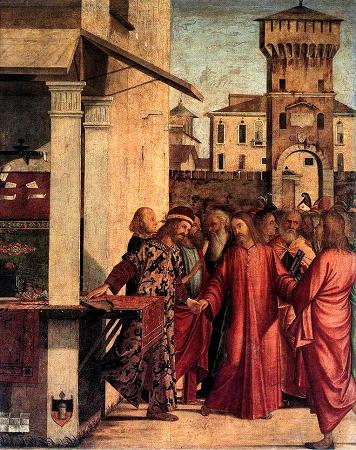

Vittore Carpaccio (c1455 - c1526). Vittore Carpaccio was an Italian painter of the Venetian school, who studied under Gentile Bellini. He is best known for a cycle of nine paintings, The Legend of Saint Ursula. His style was somewhat conservative, showing little influence from the Humanist trends that transformed Italian Renaissance painting during his lifetime. He was influenced by the style of Antonello da Messina and Early Netherlandish art. For this reason, and also because so much of his best work remains in Venice, his art has been rather neglected by comparison with other Venetian contemporaries, such as Giovanni Bellini or Giorgione. Carpaccio was born in Venice, the son of Piero Scarpazza, a leather merchant. Carpaccio, or Scarpazza, as the name was originally rendered, came from a family originally from Mazzorbo, an island in the diocese of Torcello. Documents trace the family back to at least the 13th century, and its members were diffused and established throughout Venice. His date of birth is uncertain: his principal works were executed between 1490 and 1519, ranking him among the early masters of the Venetian Renaissance, and he is first mentioned in 1472 in a will of his uncle Fra Ilario. Upon entering the Humanist circles of Venice, he changed his family name to Carpaccio. He was a pupil of Lazzaro Bastiani, who, like the Bellini and Vivarini, was the head of a large atelier in Venice. Carpaccio's earliest known solo works are a Salvator Mundi in the Collezione Contini Bonacossi and a Pieta now in the Palazzo Pitti. These works clearly show the influence of Antonello da Messina and Giovanni Bellini-especially in the use of light and colors-as well as the influence of the schools of Ferrara and Forli. In 1490 Carpaccio began the famous Legend of St. Ursula, for the Venetian Scuola dedicated to that saint. The subject of the works, which are now in the Gallerie dell'Accademia, was drawn from the Golden Legend of Jacopo da Varagine. In 1491 he completed the Glory of St. Ursula altarpiece. Indeed, many of Carpaccio's major works were of this type: large scale detachable wall-paintings for the halls of Venetian scuole, which were charitable and social confraternities. Three years later he took part in the decoration of the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista, painting the Miracle of the Relic of the Cross at the Ponte di Rialto. In the opening decade of the sixteenth century, Carpaccio embarked on the works that have since awarded him the distinction as the foremost orientalist painter of his age. From 1502 to 1507 Carpaccio executed another notable series of panels for the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni which served one of Venice's immigrant communities. Unlike the slightly old-fashioned use of a continuous narrative sequence found in the St. Ursula series, wherein the main characters appear multiple times within each canvas, each work in the Schiavoni series concentrates on a single episode in the lives of the Dalmatian's three patron Saints: St. Jerome, St. George and St. Trifon. These works are thought of as orientalist because they offer evidence of a new fascination with the Levant: a distinctly middle-eastern looking landscape takes an increasing role in the images as the backdrop to the religious scenes. Moreover, several of the scenes deal directly with cross-cultural issues, such as translation and conversion. For example, St. Jerome, translated the Greek Bible to Latin in the fourth century. Then the St. George story addressed the theme of conversion and the supremacy of Christianity. According to the Golden Legend, George, a Christian knight, rescues a Libyan princess who has been offered in sacrifice to a dragon. Horrified that her pagan family would do such a thing, George brings the dragon back to her town and compels them into being baptized. The St. George tale was enormously popular during the renaissance, and the confrontation between the knight and the dragon was painted by numerous artists. Carpaccio's depiction of the event thus has a long history; less common is his rendition of the baptism moment. Although unusual in the history of St. George pictures, St. George Baptizing the Selenites offers a good example of the type of oriental subjects were popular in Venice at the time: great care and attention is given the foreign costumes, and hats are especially significant in indicating the exotic. Note that in The Baptism one of the recent converts has ostentatiously placed his elaborate red-and-white, jewel-tipped turban on the ground in order to receive the sacrament.

more...