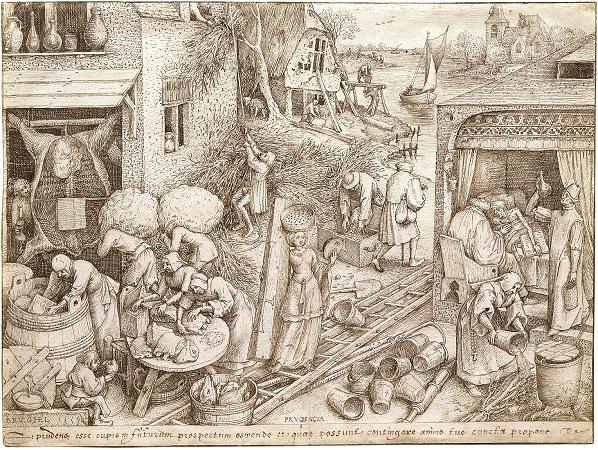

Prudence. Prudence is the ability to govern and discipline oneself by the use of reason. It is classically considered to be a virtue, and in particular one of the four Cardinal virtues. Prudentia is an allegorical female personification of the virtue, whose attributes are a mirror and snake, who is frequently depicted as a pair with Justitia, the Roman goddess of Justice. The word derives from the 14th-century Old French word prudence, which, in turn, derives from the Latin prudentia meaning foresight, sagacity. It is often associated with wisdom, insight, and knowledge. In this case, the virtue is the ability to judge between virtuous and vicious actions, not only in a general sense, but with regard to appropriate actions at a given time and place. Although prudence itself does not perform any actions, and is concerned solely with knowledge, all virtues had to be regulated by it. Distinguishing when acts are courageous, as opposed to reckless or cowardly, is an act of prudence, and for this reason it is classified as a cardinal virtue. In modern English, the word has become increasingly synonymous with cautiousness. In this sense, prudence names a reluctance to take risks, which remains a virtue with respect to unnecessary risks, but, when unreasonably extended into over-cautiousness, can become the vice of cowardice. In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle gives a lengthy account of the virtue phronesis, traditionally translated as prudence, although this has become increasingly problematic as the word has fallen out of common usage. More recently has been translated by such terms as practical wisdom, practical judgment or rational choice. Prudence was considered by the ancient Greeks and later on by Christian philosophers, most notably Thomas Aquinas, as the cause, measure and form of all virtues. It is considered to be the auriga virtutum or the charioteer of the virtues. It is the cause in the sense that the virtues, which are defined to be the perfected ability of man as a spiritual person, achieve their perfection only when they are founded upon prudence, that is to say upon the perfected ability to make right decisions. For instance, a person can live temperance when he has acquired the habit of deciding correctly the actions to take in response to his instinctual cravings. The function of a prudence is to point out which course of action is to be taken in any concrete circumstances. It has nothing to do with directly willing the good it discerns. Prudence has a directive capacity with regard to the other virtues. It lights the way and measures the arena for their exercise. Without prudence, bravery becomes foolhardiness; mercy sinks into weakness, free self-expression and kindness into censure, humility into degradation and arrogance, selflessness into corruption, and temperance into fanaticism. Culture and disciplined actions should be about the beneficial action. Its office is to determine for each in practice those circumstances of time, place, manner, etc. which should be observed, and which the Scholastics comprise under the term medium rationis. So it is that while it qualifies the intellect and not the will, it is nevertheless rightly styled a moral virtue. Prudence is considered the measure of moral virtues since it provides a model of ethically good actions. The work of art is true and real by its correspondence with the pattern of its prototype in the mind of the artist. In similar fashion, the free activity of man is good by its correspondence with the pattern of prudence. For instance, a stockbroker using his experience and all the data available to him decides that it is beneficial to sell stock A at 2PM tomorrow and buy stock B today. The content of the decision is the product of an act of prudence, while the actual carrying out of the decision may involve other virtues like fortitude and justice. The actual act's goodness is measured against that original decision made through prudence. In Greek and Scholastic philosophy, form is the specific characteristic of a thing that makes it what it is. With this language, prudence confers upon other virtues the form of its inner essence; that is, its specific character as a virtue. For instance, not all acts of telling the truth are considered good, considered as done with the virtue of honesty. What makes telling the truth a virtue is whether it is done with prudence. In Christian understanding, the difference between prudence and cunning lies in the intent with which the decision of the context of an action is made. The Christian understanding of the world includes the existence of God, the natural law and moral implications of human actions. In this context, prudence is different from cunning in that it takes into account the supernatural good.

more...