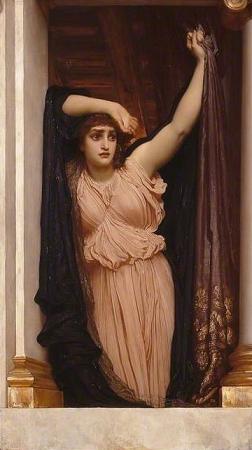

Hero and Leander. Hero and Leander is the Greek myth relating the story of Hero, a priestess of Aphrodite who dwelt in a tower in Sestos on the European side of the Hellespont, and Leander, a young man from Abydos on the opposite side of the strait. Leander fell in love with Hero and would swim every night across the Hellespont to spend time with her. Hero would light a lamp at the top of her tower to guide his way. Succumbing to Leander's soft words and to his argument that Aphrodite, as the goddess of love and sex, would scorn the worship of a virgin, Hero allowed him to make love to her, that is, she did not refuse any longer. Their trysts lasted through a warm summer. But one stormy winter night, the waves tossed Leander in the sea and the breezes blew out Hero's light; Leander lost his way and drowned. When Hero saw his dead body, she threw herself over the edge of the tower to her death to be with him. The myth of Hero and Leander has been used extensively in literature and the arts: Ancient Roman coins of Abydos: Septimius Severus Caracalla. The Double Heroides treats the narrative in 18 and 19, an exchange of letters between the lovers. Leander has been unable to swim across to Hero in her tower because of bad weather; her summons to him to make the effort will prove fatal to her lover. Francisco Quevedo mentions Leander in En crespa tempestad del oro undoso. Byzantine poet Musaeus also wrote a poem; Aldus Manutius made it one of his first publications after he set up his famous printing press in Venice. Musaeus's poem had early translations into European languages by Bernardo Tasso, Boscon and Clement Marot. This poem was widely believed in the Renaissance to have been pre-Homeric: George Chapman reflects at the end of his completion of Marlowe's version that the dead lovers had the honour of being the first that ever poet sung. Chapman's 1616 translation has the title The divine poem of Musaeus. First of all bookes. Translated according to the original, by Geo: Chapman. Staplyton, the mid-17th century translator, had read Scaliger's repudiation of this mistaken belief, but still could not resist citing Virgil's Musaeum ante omnes on the title page of his translation. Renaissance poet Christopher Marlowe began an expansive version of the narrative. His story does not get as far as Leander's nocturnal swim, and the guiding lamp that gets extinguished, but ends after the two have become lovers;. George Chapman completed Marlowe's poem after Marlowe's death; this version was often reprinted in the first half of the 17th century, with editions in 1598; 1600 and 1606; 1609, 1613, 1617, 1622; 1629; and 1637. Sir Walter Ralegh alludes to the story, in his The Ocean's Love to Cynthia, in which Hero has fallen asleep, and fails to keep alight the lamp that guides Leander on his swim. Shakespeare also mentions this story in the opening scene of Two Gentlemen of Verona, in a dialogue between Valentine and Proteus:. VALENTINE: And on a love-book pray for my success? PROTEUS: Upon some book I love I'll pray for thee. VALENTINE: That's on some shallow story of deep love: How young Leander cross'd the Hellespont. PROTEUS: That's a deep story of a deeper love: For he was more than over shoes in love. VALENTINE: Tis true; for you are over boots in love, And yet you never swum the Hellespont. Hero and Leander are again mentioned in The Two Gentlemen of Verona in Act III Scene I when Valentine is tutoring the Duke of Milan on how to woo the lady from Milan. Shakespeare also alludes to the story in Much Ado About Nothing, both when Benedick states that Leander was never so truly turned over and over as my poor self in love and in the name of the character Hero, who, despite accusations to the contrary, remains chaste before her marriage; and in A Midsummer Night's Dream in the form of a malapropism accidentally using the names Helen and Limander in the place of Hero and Leander, as well as in Edward III, Othello, and Romeo and Juliet. The most famous Shakespearean allusion is the debunking one by Rosalind, in Act IV scene I of As You Like It: Leander, he would have lived many a fair year, though Hero had turned nun, if it had not been for a hot midsummer night; for, good youth, he went but forth to wash him in the Hellespont and being taken with the cramp was drowned and the foolish coroners of that age found it was Hero of Sestos. But these are all lies: men have died from time to time and worms have eaten them, but not for love. Ben Jonson's play Bartholomew Fair features a puppet show of Hero and Leander in Act V, translated to London, with the Thames serving as the Hellespont between the lovers.

more...