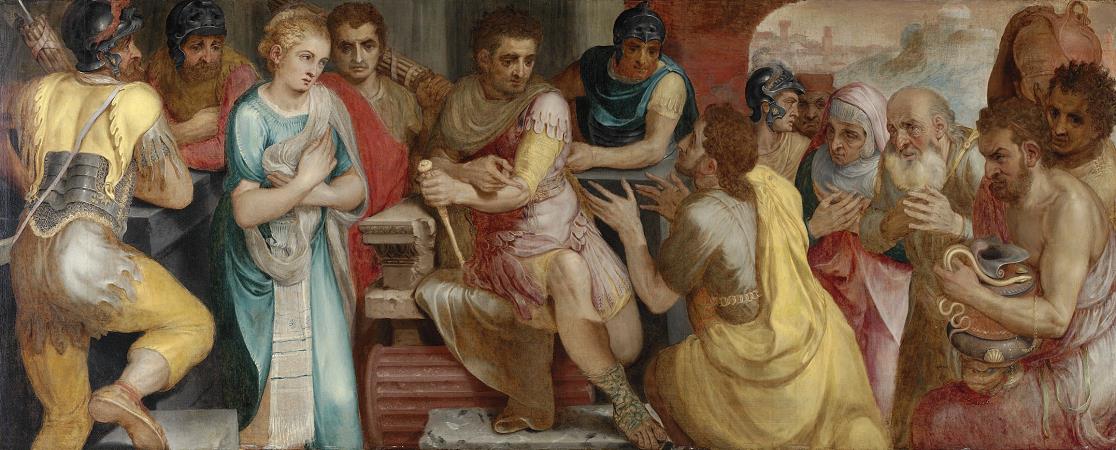

Continence of Scipio (c-209). The Continence of Scipio, or The Clemency of Scipio, is an episode recounted by Livy of the Roman general Scipio Africanus during his campaign in Spain during the Second Punic War. He refused a generous ransom for a young female prisoner, returning her to her fiance Allucius, who in return became a supporter of Rome. In recognition of his magnanimous treatment of a prisoner, he was taken as one of the prime examples of mercy during warfare in classical times. Interest in the story revived in the Renaissance and the episode figured widely thereafter in both the literary and figurative arts. The story related by Livy in his history of Rome was followed by all later writers, although it is recorded that the earlier historian Valerius Antias took a dissenting view. According to Livy's account of the siege of the Carthaginian colony of New Carthage, the Celtiberian prince Allucius was betrothed to a beautiful virgin who was taken prisoner by Scipio Africanus in 209 BC. Despite having a reputation for womanizing, instead of the usual brutal treatment given to attractive female barbarian prisoners, Scipio summoned her parents and fiance, who arrived with a ransom of treasure. Scipio refused this and returned her to them, asking only that they be friends to Rome. When they offered the ransom as a present, he accepted it, only to return it immediately as a wedding gift from himself. Allucius then brought over his tribe to support the Roman armies in gratitude. This episode was a popular motif for exemplary literature from that time on, growing to a peak of popularity during the 17th and 18th centuries. Prior to this period, it was given pride of place in the story of Scipio inserted into translations of Plutarch's Lives that was written originally by the Dutchman Carolus Clusius in 1567. Among dramatic treatments of the story, one of the foremost was the Scipion of Jean Desmarets, which was then adapted into Dutch by Jan Lemmers as Schipio in Karthago and also performed later as Schipio en Olinde. In England a verse drama on the episode, Scipio Africanus, was chiefly distinguished by being the work of a schoolboy, Charles Beckingham. It was acted and later printed in 1718. Operatic treatments were numerous, with several composers setting the same libretto. So, for example, Nicolo Minato's Scipione Africano was set, or served as the basis for adaptations, by Francesco Cavalli; Carlo Ambrogio Lonati; Francesco Bianchi; and Gioacchino Albertini. In addition, there was Johann Sigismund Kusser's German version, Der grossmutige Scipio Africanus. Giovanni Battista Boccabadati's prose drama Scipione served as the basis for Apostolo Zeno's Scipione nelle Spagne. This was performed in 1710, with music possibly by Antonio Caldara, and was also set by Alessandro Scarlatti, Tomaso Albinoni, George Friederic Handel, Carlo Arrigoni, and Leonardo Leo. Johann Christian Bach's La Clemenza di Scipione was also based upon it. There were numerous artistic depictions of the mercy and sexual restraint of Scipio although, as with the operas, they go now by a variety of titles. The Continence of Scipio is most common in English, although The Clemency of Scipio is also found. In other languages the terms magnanimity and generosity are alternatives. There is also sometimes a difficulty in identifying which scene is intended. The most common alternative example of military clemency descending from classical times was Alexander the Great's generous treatment of the family of the defeated Persian King Darius, best known from Veronese's painting in London. The scene of a victorious general seated at the centre of the composition with kneeling figures before him might portray either story without other clues to its interpretation. Typically, Scipio sits on a throne on a raised dias, stretching out an arm in the direction of the Spanish party, with their treasure laid out in front of them. The continence shown by Scipio is both sexual and financial. The story of Timoclea and Alexander the Great is rather different, but produces similar compositions of a woman brought before a magnanimous classical commander, which sometimes accompanied the Continence in a series, and is also capable of being confused with it. Bernard de Montfaucon paired the two stories as his Examples of the clemency and continence of conquerors in a book of 1724. Tapestry series based on the exploits of Scipio, which would often portray this scene, was one contextual identifier; so was connection with the histories of Livy or the expanded Plutarch for which the numerous surviving prints were intended, or on which they were dependent.

more...