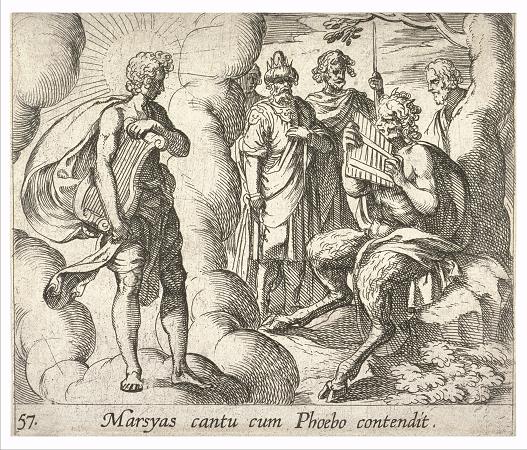

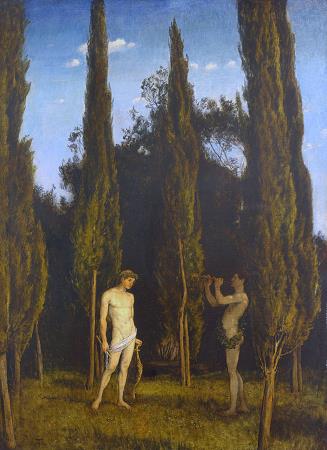

Marsyas. In Greek mythology, the satyr Marsyas is a central figure in two stories involving music: in one, he picked up the double oboe that had been abandoned by Athena and played it; in the other, he challenged Apollo to a contest of music and lost his hide and life. In antiquity, literary sources often emphasise the hubris of Marsyas and the justice of his punishment. In one strand of modern comparative mythography, the domination of Marsyas by Apollo is regarded as an example of myth that recapitulates a supposed supplanting by the Olympian pantheon of an earlier Pelasgian religion of chthonic heroic ancestors and nature spirits. Marsyas was a devoté of the ancient Mother Goddess Rhea / Cybele, and his episodes are situated by the mythographers in Celaenae, in Phrygia, at the main source of the Meander. When a genealogy was applied to him, Marsyas was the son of Olympus, or of Oeagrus, or of Hyagnis. Olympus was, alternatively, said to be Marsyas' son or pupil. Marsyas was an expert player on the double-piped double reed instrument known as the aulos. The dithyrambic poet Melanippides of Melos embellished the story in his dithyramb Marsyas, claiming that the goddess Athena, who was already said to have invented the aulos, once looked in the mirror while she was playing it and saw how blowing into it puffed up her cheeks and made her look silly, so she threw the aulos away and cursed it so that whoever picked it up would meet an awful death. Marsyas picked up the aulos and was later killed by Apollo for his hubris. The fifth-century BC poet Telestes doubted that virginal Athena could have been motivated by such vanity. Some account informs about the curse placed on the bearer of the flute, i.e; Athena placed a curse that the one picking up the flute would be severely punished. Later, however, Melanippides's story became accepted as canonical and the Athenian sculptor Myron created a group of bronze sculptures based on it, which was installed before the western front of the Parthenon in around 440 BC. In the second century AD, the travel writer Pausanias saw this set of sculptures and described it as a statue of Athena striking Marsyas the Silenos for taking up the flutes that the goddess wished to be cast away for good. In the contest between Apollo and Marsyas, which was judged by the Muses or the Nysean nymphs the terms stated that the winner could treat the defeated party any way he wanted. Marsyas played his flute, putting everyone there into a frenzy, and they started dancing wildly. When it was Apollo's turn, he played his lyre so beautifully that everyone was still and had tears in their eyes. There are several versions of the contest; according to Hyginus, Marsyas was departing as victor after the first round, when Apollo, turning his lyre upside down, played the same tune. This was something that Marsyas could not do with his flute. According to Diodorus Siculus, Marsyas was defeated when Apollo added his voice to the sound of the lyre. Marsyas protested, arguing that the skill with the instrument was to be compared, not the voice. However, Apollo replied that when Marsyas blew into the pipes, he was doing almost the same thing himself. The Nysean nymphs supported Apollo's claim, leading to his victory. Yet another version states that Marsyas played the flute out of tune, and hence accepted his defeat. Out of shame, he assigned to himself the penalty of being skinned for a winesack. He was flayed alive in a cave near Celaenae for his hubris to challenge a god. Apollo then nailed Marsyas' skin to a pine tree, near Lake Aulocrene, which Strabo noted was full of the reeds from which the pipes were fashioned. Diodorus Siculus felt that Apollo must have repented this excessive deed, and said that he had laid aside his lyre for a while, but Karl Kerenyi observes of the flaying of Marsyas' shaggy hide: a penalty which will not seem especially cruel if one assumes that Marsyas' animal guise was merely a masquerade. Classical Greeks were unaware of such shamanistic overtones, and the Flaying of Marsyas became a theme for painting and sculpture. His brothers, nymphs, gods and goddesses mourned his death, and their tears, according to Ovid's Metamorphoses, were the source of the river Marsyas in Phrygia, which joins the Meander near Celaenae, where Herodotus reported that the flayed skin of Marsyas was still to be seen, and Ptolemy Hephaestion recorded a festival of Apollo, where the skins of all those victims one has flayed are offered to the god. Plato was of the opinion that it had been made into a wineskin. Ovid touches upon the theme of Marsyas twice, very briefly telling the tale in Metamorphoses vi.

more...