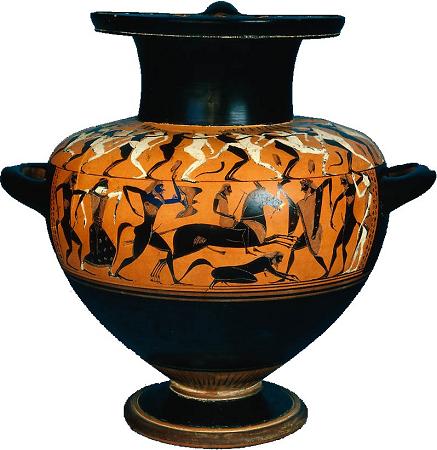

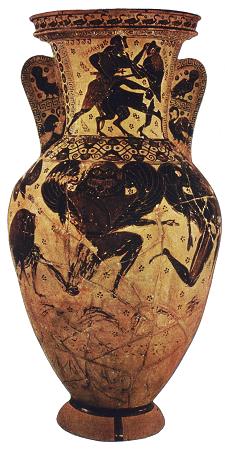

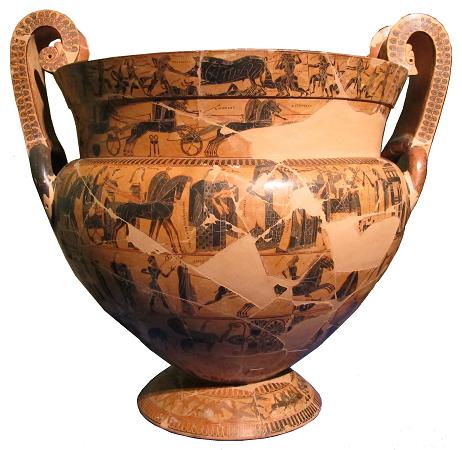

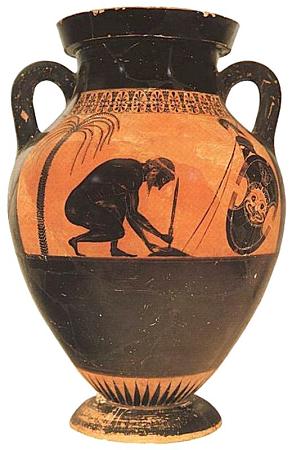

Black-Figure Ceramic. Black-figure pottery painting, also known as the black-figure style or black-figure ceramic is one of the styles of painting on antique Greek vases. It was especially common between the 7th and 5th centuries BC, although there are specimens dating as late as the 2nd century BC. Stylistically it can be distinguished from the preceding orientalizing period and the subsequent red-figure pottery style. Figures and ornaments were painted on the body of the vessel using shapes and colors reminiscent of silhouettes. Delicate contours were incised into the paint before firing, and details could be reinforced and highlighted with opaque colors, usually white and red. The principal centers for this style were initially the commercial hub Corinth, and later Athens. Other important production sites are known to have been in Laconia, Boeotia, eastern Greece, and Italy. Particularly in Italy individual styles developed which were at least in part intended for the Etruscan market. Greek black-figure vases were very popular with the Etruscans, as is evident from frequent imports. Greek artists created customized goods for the Etruscan market which differed in form and decor from their normal products. The Etruscans also developed their own black-figure ceramic industry oriented on Greek models. Black-figure painting on vases was the first art style to give rise to a significant number of identifiable artists. Some are known by their true names, others only by the pragmatic names they were given in the scientific literature. Especially Attica was the home of well-known artists. Some potters introduced a variety of innovations which frequently influenced the work of the painters; sometimes it was the painters who inspired the potters' originality. Red-as well as black-figure vases are one of the most important sources of mythology and iconography, and sometimes also for researching day-to-day ancient Greek life. Since the 19th century at the latest, these vases have been the subject of intensive investigation. The foundation for pottery painting is the image carrier, in other words the vase onto which an image is painted. Popular shapes alternated with passing fashions. Whereas many recurred after intervals, others were replaced over time. But they all had a common method of manufacture: after the vase was made, it was first dried before being painted. The workshops were under the control of the potters, who as owners of businesses had an elevated social position. The extent to which potters and painters were identical is uncertain. It is likely that many master potters themselves made their main contribution in the production process as vase painters, while employing additional painters. It is, however, not easy to reconstruct links between potters and painters. In many cases, such as Tleson and the Tleson Painter, Amasis and the Amasis Painter or even Nikosthenes and Painter N, it is impossible to make unambiguous attributions, although in much of the scientific literature these painters and potters are assumed to be the same person. But such attributions can only be made with confidence if the signatures of potter and painter are at hand. The painters, who were either slaves or craftsmen paid as pottery painters, worked on unfired, leather-dry vases. In the case of black-figure production the subject was painted on the vase with a clay slurry which turned black and glossy after firing. This was not paint in the usual sense, since this surface slip was made from the same clay material as the vase itself, only differing in the size of the component particles, achieved during refining the clay before potting began. The area for the figures was first painted with a brush-like implement. The internal outlines and structural details were incised into the slip so that the underlying clay could be seen through the scratches. Two other earth-based pigments giving red and white were used to add details such as ornaments, clothing or parts of clothing, hair, animal manes, parts of weapons and other equipment. White was also frequently used to represent women's skin. The success of all this effort could only be judged after a complicated, three-phase firing process which generated the red color of the body clay and the black of the applied slip. Specifically, the vessel was fired in a kiln at a temperature of about 800 °C, with the resultant oxidization turning the vase a reddish-orange color. The temperature was then raised to about 950 °C with the kiln's vents closed and green wood added to remove the oxygen. The vessel then turned an overall black.

more...