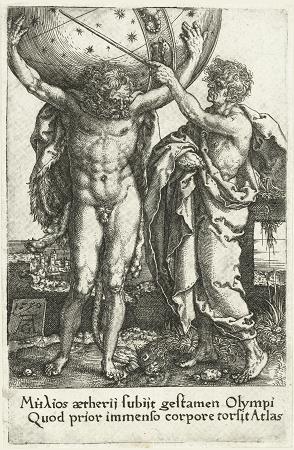

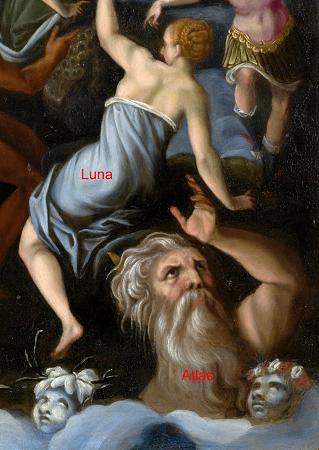

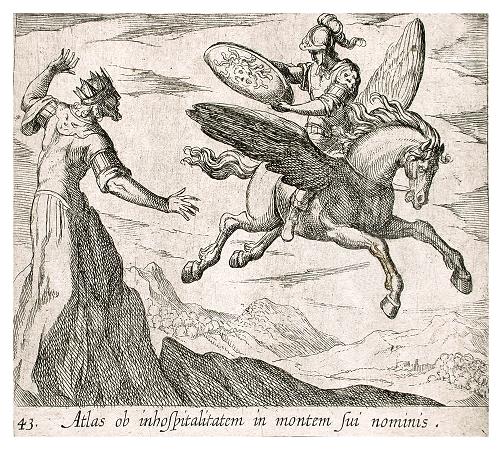

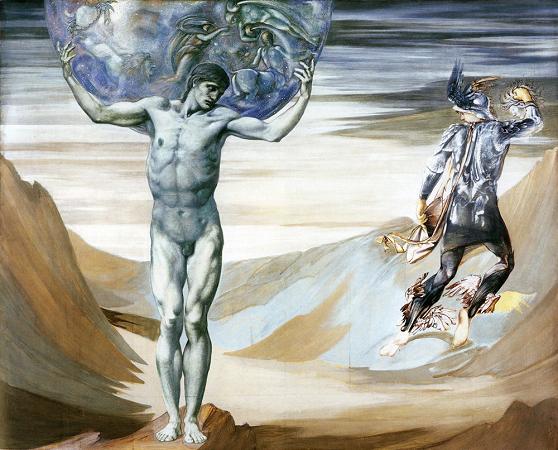

Atlas. In Greek mythology, Atlas was a titan condemned to hold up the celestial heavens for eternity after the Titanomachy. Atlas also plays a role in the myths of two of the greatest Greek heroes: Heracles and Perseus. According to the ancient Greek poet Hesiod, Atlas stood at the ends of the earth in extreme west. Later, he became commonly identified with the Atlas Mountains in northwest Africa and was said to be the first King of Mauretania. Atlas was said to have been skilled in philosophy, mathematics, and astronomy. In antiquity, he was credited with inventing the first celestial sphere. In some texts, he is even credited with the invention of astronomy itself. Atlas was the son of the Titan Iapetus and the Oceanid Asia or Clymene. He had many children, mostly daughters, the Hesperides, the Hyades, the Pleiades, and the nymph Calypso who lived on the island Ogygia. The term Atlas has been used to describe a collection of maps since the 16th century when Flemish geographer Gerardus Mercator published his work in honor of the mythological Titan. The Atlantic Ocean is derived from Sea of Atlas. The etymology of the name Atlas is uncertain. Virgil took pleasure in translating etymologies of Greek names by combining them with adjectives that explained them: for Atlas his adjective is durus, hard, enduring, which suggested to George Doig that Virgil was aware of the Greek tarjvai to endure; Doig offers the further possibility that Virgil was aware of Strabo's remark that the native North African name for this mountain was Douris. However, Robert Beekes argues that it cannot be expected that this ancient Titan carries an Indo-European name, and that the word is of Pre-Greek origin, and such words often end in-ant. Titanomachy Atlas and his brother Menoetius sided with the Titans in their war against the Olympians, the Titanomachy. When the Titans were defeated, many of them were confined to Tartarus, but Zeus condemned Atlas to stand at the western edge of Gaia and hold up the sky on his shoulders. Thus, he was Atlas Telamon, enduring Atlas, and became a doublet of Coeus, the embodiment of the celestial axis around which the heavens revolve. A common misconception today is that Atlas was forced to hold the Earth on his shoulders, but Classical art shows Atlas holding the celestial spheres, not the terrestrial globe; the solidity of the marble globe borne by the renowned Farnese Atlas may have aided the conflation, reinforced in the 16th century by the developing usage of atlas to describe a corpus of terrestrial maps. The Greek poet Polyidus ca. 398 BC tells a tale of Atlas, then a shepherd, encountering Perseus who turned him to stone. Ovid later gives a more detailed account of the incident, combining it with the myth of Heracles. In this account Atlas is not a shepherd but a King. According to Ovid, Perseus arrives in Atlas' Kingdom and asks for shelter, declaring he is a son of Zeus. Atlas, fearful of a prophecy which warned of a son of Zeus stealing his golden apples from his orchard, refuses Perseus hospitality. In this account, Atlas is turned not just into stone by Perseus, but an entire mountain range: Atlas' head the peak, his shoulders ridges and his hair woods. The prophecy did not relate to Perseus stealing the golden apples but Heracles, another son of Zeus, and Perseus' great-grandson. One of the Twelve Labors of the hero Heracles was to fetch some of the golden apples which grow in Hera's garden, tended by Atlas' reputed daughters, the Hesperides which were also called the Atlantides, and guarded by the dragon Ladon. Heracles went to Atlas and offered to hold up the heavens while Atlas got the apples from his daughters. Upon his return with the apples, however, Atlas attempted to trick Heracles into carrying the sky permanently by offering to deliver the apples himself, as anyone who purposely took the burden must carry it forever, or until someone else took it away.

more...