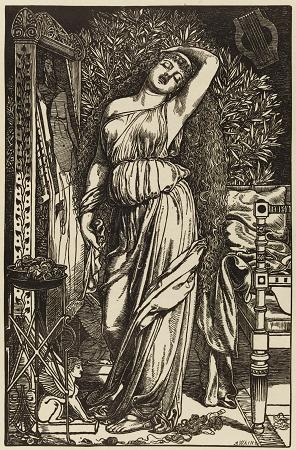

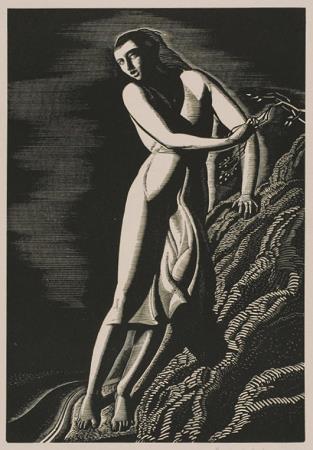

Wood Engraving. Wood engraving is a printmaking and letterpress printing technique, in which an artist works an image or matrix of images into a block of wood. Functionally a variety of woodcut, it uses relief printing, where the artist applies ink to the face of the block and prints using relatively low pressure. By contrast, ordinary engraving, like etching, uses a metal plate for the matrix, and is printed by the intaglio method, where the ink fills the valleys, the removed areas. As a result, wood engravings deteriorate less quickly than copper-plate engravings, and have a distinctive white-on-black character. Thomas Bewick developed the wood engraving technique in Great Britain at the end of the 18th century. His work differed from earlier woodcuts in two key ways. First, rather than using woodcarving tools such as knives, Bewick used an engraver's burin. With this, he could create thin delicate lines, often creating large dark areas in the composition. Second, wood engraving traditionally uses the wood's end grain, while the older technique used the softer side grain. The resulting increased hardness and durability facilitated more detailed images. Wood-engraved blocks could be used on conventional printing presses, which were going through rapid mechanical improvements during the first quarter of the 19th century. The blocks were made the same height as, and composited alongside, movable type in page layouts, so printers could produce thousands of copies of illustrated pages with almost no deterioration. The combination of this new wood engraving method and mechanized printing drove a rapid expansion of illustrations in the 19th century. Further, advances in stereotype let wood-engravings be reproduced onto metal, where they could be mass-produced for sale to printers. By the mid-19th century, many wood engravings rivaled copperplate engravings. Wood engraving was used to great effect by 19th-century artists such as Edward Calvert, and its heyday lasted until the early and mid-20th century when remarkable achievements were made by Eric Gill, Eric Ravilious, Tirzah Garwood and others. Though less used now, the technique is still prized in the early 21st century as a high-quality specialist technique of book illustration, and is promoted, for example, by the Society of Wood Engravers, who hold an annual exhibition in London and other British venues. In 15th-and 16th-century Europe, woodcuts were a common technique in printmaking and printing, yet their use as an artistic medium began to decline in the 17th century. They were still made for basic printing press work such as newspapers or almanacs. These required simple blocks that printed in relief with the text, rather than the elaborate intaglio forms in book illustrations and artistic printmaking at the time, in which type and illustrations were printed with separate plates and techniques. The beginnings of modern wood engraving techniques developed at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century, with the works of Englishman Thomas Bewick. Bewick generally engraved harder woods, such as boxwood, rather than the woods used in woodcuts, and he engraved the ends of blocks instead of the side. Finding a woodcutting knife not suitable for working against the grain in harder woods, Bewick used a burin, an engraving tool with a V-shaped cutting tip. From the beginning of the nineteenth century Bewick's techniques gradually came into wider use, especially in Britain and the United States. Alexander Anderson introduced the technique to the United States. Bewick's work impressed him, so he reverse engineered and imitated Bewick's technique, using metal until he learned that Bewick used wood. There it was further expanded upon by his students, Joseph Alexander Adams. Besides interpreting details of light and shade, from the 1820s onwards, engravers used the method to reproduce freehand line drawings. This was, in many ways an unnatural application, since engravers had to cut away almost all the surface of the block to produce the printable lines of the artist's drawing. Nonetheless, it became the most common use of wood engraving. Examples include the cartoons of Punch magazine, the pictures in the Illustrated London News and Sir John Tenniel's illustrations to Lewis Carroll's works, the latter engraved by the firm of Dalziel Brothers. In the United States, wood-engraved publications also began to take hold, such as Harper's Weekly. Frank Leslie, a British-born engraver who had headed the engraving department of the Illustrated London News, immigrated to the United States in 1848, where he developed a means to divide the labor for making wood engravings. A single design was divided into a grid, and each engraver worked on a square. The blocks were then assembled into a single image.

more...