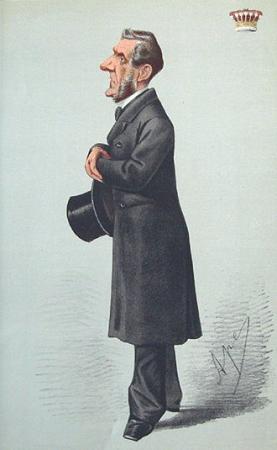

Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury (1801 - 1886). Anthony Ashley Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury, styled Lord Ashley from 1811 to 1851 and then Lord Shaftesbury following the death of his father, was a British politician, philanthropist and social reformer. He was the eldest son of Cropley Ashley-Cooper, 6th Earl of Shaftesbury and his wife Lady Anne Spencer, daughter of George Spencer, 4th Duke of Marlborough, and older brother of Henry Ashley, MP. Lord Ashley, as he was styled until his father's death in 1851, was educated at Manor House school in Chiswick, Harrow School and Christ Church, Oxford, where he gained first class honours in classics in 1822, took his MA in 1832 and was appointed DCL in 1841. Ashley's early family life was loveless, a circumstance common among the British upper classes, and resembled in that respect the fictional childhood of Esther Summerson vividly narrated in the early chapters of Charles Dickens's novel Bleak House. G.F.A Best in his biography Shaftesbury writes that: Ashley grew up without any experience of parental love. He saw little of his parents, and when duty or necessity compelled them to take notice of him they were formal and frightening. Even as an adult, he disliked his father and was known to refer to his mother as a devil. This difficult childhood was softened by the affection he received from his housekeeper Maria Millis, and his sisters. Millis provided for Ashley a model of Christian love that would form the basis for much of his later social activism and philanthropic work, as Best explains: What did touch him was the reality, and the homely practicality, of the love which her Christianity made her feel towards the unhappy child. She told him bible stories, she taught him a prayer. Despite this powerful reprieve, school became another source of misery for the young Ashley, whose education at Manor House from 1808 to 1813 introduced a more disgusting range of horrors. Shaftesbury himself shuddered to recall those years, The place was bad, wicked, filthy; and the treatment was starvation and cruelty. By teenage years he had become a committed Christian and whilst at Harrow two experiences happened that would influence his later life. Once, at the foot of Harrow Hill, he was the horrified witness of a pauper's funeral. The drunken pall-bearers, stumbling along with a crudely-made coffin and shouting snatches of bawdy songs, brought home to him the existence of a whole empire of callousness which put his own childhood miseries in their context. The second incident was his unusual choice of a subject for a Latin poem. In the school grounds, there was an unsavoury mosquito-breeding pond called the Duck Puddle. He chose it as his subject because he was urgently concerned that the school authorities should do something about it, and this appeared to be the simplest way of bringing it to their attention. Soon afterwards the Duck Puddle was inspected, condemned and filled in. This little triumph was a useful fillip to his self-confidence, but it was more than that. It was a foretaste of his skill in getting people to act decisively in face of sloth or immediate self-interest. This was to prove one of his greatest assets in Parliament. Ashley was elected as the Tory Member of Parliament for Woodstock in June 1826 and was a strong supporter of the Duke of Wellington. After George Canning replaced Lord Liverpool as Prime Minister, he offered Ashley a place in the new government, despite Ashley having been in the Commons for only five months. Ashley politely declined, writing in his diary that he believed that serving under Canning would be a betrayal of his allegiance to the Duke of Wellington and that he was not qualified for office. Before he had completed one year in the Commons, he had been appointed to three parliamentary committees and he received his fourth such appointment in June 1827, when he was appointed to the Select Committee On Pauper Lunatics in the County of Middlesex and on Lunatic Asylums. In 1827, when Ashley-Cooper was appointed to the Select Committee On Pauper Lunatics in the County of Middlesex and on Lunatic Asylums, the majority of lunatics in London were kept in madhouses owned by Dr Warburton. The Committee examined many witnesses concerning one of his madhouses in Bethnal Green, called the White House. Ashley visited this on the Committee's behalf. The patients were chained up, slept naked on straw, and went to toilet in their beds. They were left chained from Saturday afternoon until Monday morning when they were cleared of the accumulated excrement. They were then washed down in freezing cold water and one towel was allotted to 160 people, with no soap.

more...