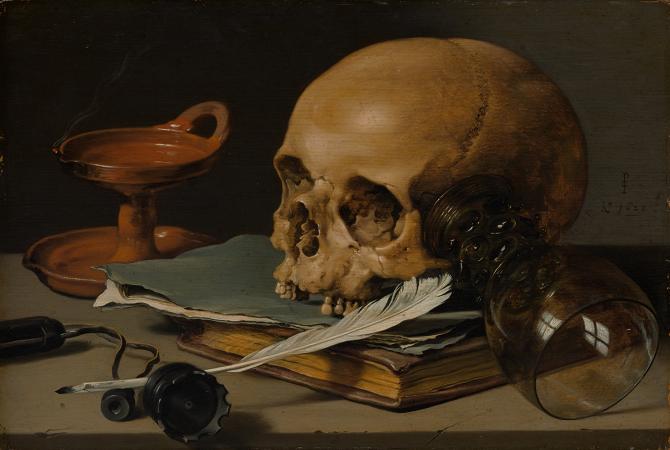

Still Life. A still life is a work of art depicting mostly inanimate subject matter, typically commonplace objects which are either natural or man-made. With origins in the Middle Ages and Ancient Greco-Roman art, still-life painting emerged as a distinct genre and professional specialization in Western painting by the late 16th century, and has remained significant since then. One advantage of the still-life artform is that it allows an artist a lot of freedom to experiment with the arrangement of elements within a composition of a painting. Still life, as a particular genre, began with Netherlandish painting of the 16th and 17th centuries, and the English term still life derives from the Dutch word stilleven. Early still-life paintings, particularly before 1700, often contained religious and allegorical symbolism relating to the objects depicted. Later still-life works are produced with a variety of media and technology, such as found objects, photography, computer graphics, as well as video and sound. The term includes the painting of dead animals, especially game. Live ones are considered animal art, although in practice they were often painted from dead models. Because of the use of plants and animals as a subject, the still-life category also shares commonalities with zoological and especially botanical illustration. However, with visual or fine art, the work is not intended merely to illustrate the subject correctly. Still life occupied the lowest rung of the hierarchy of genres, but has been extremely popular with buyers. As well as the independent still-life subject, still-life painting encompasses other types of painting with prominent still-life elements, usually symbolic, and images that rely on a multitude of still-life elements ostensibly to reproduce a 'slice of life. The trompe-l'oeil painting, which intends to deceive the viewer into thinking the scene is real, is a specialized type of still life, usually showing inanimate and relatively flat objects. Still-life paintings often adorn the interior of ancient Egyptian tombs. It was believed that food objects and other items depicted there would, in the afterlife, become real and available for use by the deceased. Ancient Greek vase paintings also demonstrate great skill in depicting everyday objects and animals. Peiraikos is mentioned by Pliny the Elder as a panel painter of low subjects, such as survive in mosaic versions and provincial wall-paintings at Pompeii: barbers' shops, cobblers' stalls, asses, eatables and similar subjects. Similar still life, more simply decorative in intent, but with realistic perspective, have also been found in the Roman wall paintings and floor mosaics unearthed at Pompeii, Herculaneum and the Villa Boscoreale, including the later familiar motif of a glass bowl of fruit. Decorative mosaics termed emblema, found in the homes of rich Romans, demonstrated the range of food enjoyed by the upper classes, and also functioned as signs of hospitality and as celebrations of the seasons and of life. By the 16th century, food and flowers would again appear as symbols of the seasons and of the five senses. Also starting in Roman times is the tradition of the use of the skull in paintings as a symbol of mortality and earthly remains, often with the accompanying phrase Omnia mors aequat. These vanitas images have been re-interpreted through the last 400 years of art history, starting with Dutch painters around 1600. The popular appreciation of the realism of still-life painting is related in the ancient Greek legend of Zeuxis and Parrhasius, who are said to have once competed to create the most lifelike objects, history's earliest descriptions of trompe-l'oeil painting. As Pliny the Elder recorded in ancient Roman times, Greek artists centuries earlier were already advanced in the arts of portrait painting, genre painting and still life. He singled out Peiraikos, whose artistry is surpassed by only a very few.He painted barbershops and shoemakers' stalls, donkeys, vegetables, and such, and for that reason came to be called the 'painter of vulgar subjects'; yet these works are altogether delightful, and they were sold at higher prices than the greatest of many other artists. By 1300, starting with Giotto and his pupils, still-life painting was revived in the form of fictional niches on religious wall paintings which depicted everyday objects. Through the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, still life in Western art remained primarily an adjunct to Christian religious subjects, and convened religious and allegorical meaning.

more...