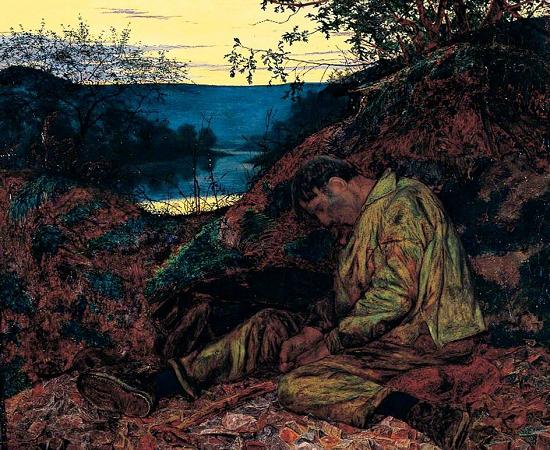

Stonebreaker. Oil on panel. 65 x 79. The Stonebreaker is an 1857 oil-on-canvas painting by Henry Wallis. It depicts a manual labourer who appears to be asleep, worn out by his work, but has actually been worked to death. The painting was first exhibited in 1858 at the Royal Academy in London and was highly acclaimed. Many viewers assumed the man was sleeping, worn out by his day of hard but honest labour. Wallis gave no outright statement that the man depicted was dead, but there are many suggestions to this effect. The frame was inscribed with a line paraphrased from Tennyson's A Dirge: Now is thy long day's work done; the muted colours and setting sun give a feeling of finality; the man's posture indicates that his hammer has slipped from his grasp as he was working rather than being laid aside while he rests, and his body is so still that a stoat, only visible on close examination, has climbed onto his right foot. The painting's listing in the catalogue was accompanied by a long passage from Thomas Carlyle's Helotage, a chapter in his Sartor Resartus, which extols the virtues of the working man and laments that thy body like thy soul was not to know freedom. Wallis is believed to have painted The Stonebreaker as a commentary on the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 which had formalised the workhouse system for paupers and discouraged other forms of relief for the poor. The able-bodied poor were forced into long hours of manual labour in order to qualify for the lodgings and food provided by the workhouse and the gruelling work sometimes resulted in the death of the workers. Carlyle's accompanying passage also has strong words for supporters of the workhouses: Perhaps in the most thickly-peopled country, some three days annually might suffice to shoot all the able-bodied Paupers that had accumulated during the year. It was later claimed that by this painting, Wallis moved away from the Pre-Raphaelite principles towards those of an early Victorian Social Realism. However, for Wallis' contemporaries, The Stonebreaker consolidated his reputation as a true Pre-Raphaelite. The dead man wears the smock of an agricultural labourer which suggests that in former times he would have been employed year-round on a farm. Changing social conditions have robbed him of his employment and forced him instead to accept the charity of the workhouse and the arduous job of flint-knapping to produce material for the roads. The painting provides a strong contrast with John Brett's painting of the same name, completed the year after Wallis's version. Brett's Stonebreaker shows another pauper breaking rocks, but this time it is a smartly dressed, well-nourished boy, accompanied by a playful puppy, working away in a bright, sunlit landscape. Brett's painting made his reputation. The details are captured with a scientific accuracy, and the painting was lauded by the art critic John Ruskin. It too makes a statement about the poor, although it lacks the hopelessness and finality of Wallis's painting, just as in Wallis's version there is an underlying realism that is not at first obvious: the boy is rosy-cheeked not because of healthy exercise, but because of the work he is forced to undertake; the puppy cavorts happily, but the boy, working for the chance of receiving charity, cannot afford to stop to play. Brett's painting is in the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool. Although Wallis's technique was admired, his choice of subject divided the critics. The Illustrated London News found it shocking and offensive while The Spectator said it embodied the sacredness and solemnity which dwell in a human creature, however seared, and in death, however obscure.

more...