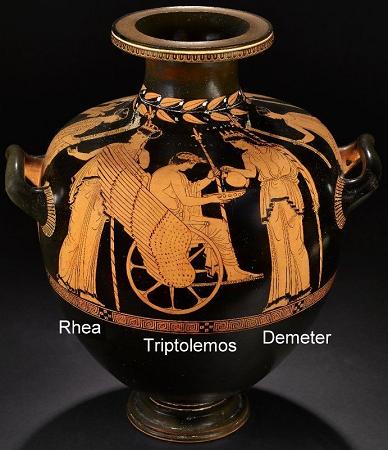

Ceres / Demeter. In ancient Roman religion, Ceres was a goddess of agriculture, grain crops, fertility and motherly relationships. She was originally the central deity in Rome's so-called plebeian or Aventine Triad, then was paired with her daughter Proserpina in what Romans described as the Greek rites of Ceres. Her seven-day April festival of Cerealia included the popular Ludi Ceriales. She was also honoured in the May lustratio of the fields at the Ambarvalia festival, at harvest-time, and during Roman marriages and funeral rites. Ceres is the only one of Rome's many agricultural deities to be listed among the Dii Consentes, Rome's equivalent to the Twelve Olympians of Greek mythology. The Romans saw her as the counterpart of the Greek goddess Demeter, whose mythology was reinterpreted for Ceres in Roman art and literature. Roman etymologists thought ceres derived from the Latin verb gerere, to bear, bring forth, produce, because the goddess was linked to pastoral, agricultural and human fertility. Archaic cults to Ceres are well-evidenced among Rome's neighbours in the Regal period, including the ancient Latins, Oscans and Sabellians, less certainly among the Etruscans and Umbrians. An archaic Faliscan inscription of c. 600 BC asks her to provide far, which was a dietary staple of the Mediterranean world. Throughout the Roman era, Ceres' name was synonymous with grain and, by extension, with bread. Ceres was credited with the discovery of spelt wheat, the yoking of oxen and ploughing, the sowing, protection and nourishing of the young seed, and the gift of agriculture to humankind; before this, it was said, man had subsisted on acorns, and wandered without settlement or laws. She had the power to fertilise, multiply and fructify plant and animal seed, and her laws and rites protected all activities of the agricultural cycle. In January, Ceres was offered spelt wheat and a pregnant sow, along with the earth-goddess Tellus, at the movable Feriae Sementivae. This was almost certainly held before the annual sowing of grain. The divine portion of sacrifice was the entrails presented in an earthenware pot. In a rural context, Cato the Elder describes the offer to Ceres of a porca praecidanea. Before the harvest, she was offered a propitiary grain sample. Ovid tells that Ceres is content with little, provided that her offerings are casta. Ceres' main festival, Cerealia, was held from mid to late April. It was organised by her plebeian aediles and included circus games. It opened with a horse-race in the Circus Maximus, whose starting point lay below and opposite to her Aventine Temple; the turning post at the far end of the Circus was sacred to Consus, a god of grain-storage. After the race, foxes were released into the Circus, their tails ablaze with lighted torches, perhaps to cleanse the growing crops and protect them from disease and vermin, or to add warmth and vitality to their growth. From c.175 BC, Cerealia included ludi scaenici through April 12 to 18. In the ancient sacrum cereale a priest, probably the Flamen Cerialis, invoked Ceres along with twelve specialised, minor assistant-gods to secure divine help and protection at each stage of the grain cycle, beginning shortly before the Feriae Sementivae. W.H. Roscher lists these deities among the indigitamenta, names used to invoke specific divine functions. Vervactor, He who ploughs. Reparator, He who prepares the earth. Imporcitor, He who ploughs with a wide furrow. Insitor, He who plants seeds. Obarator, He who traces the first ploughing. Occator, He who harrows. Serritor, He who digs. Subruncinator, He who weeds. Messor, He who reaps. Conuector, He who carries the grain. Conditor, He who stores the grain. Promitor, He who distributes the grain. In Roman bridal processions, a young boy carried Ceres' torch to light the way; the most auspicious wood for wedding torches came from the spina alba, the may tree, which bore many fruits and hence symbolised fertility.

more...