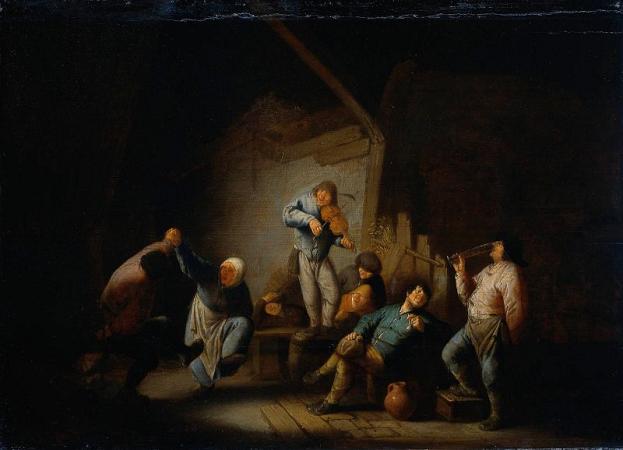

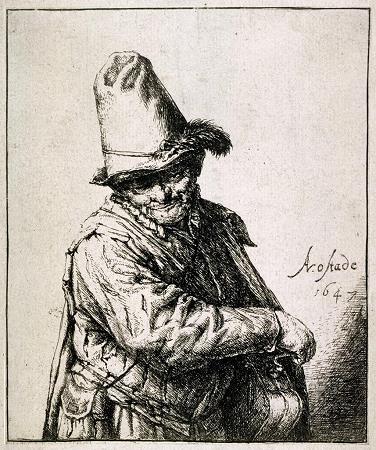

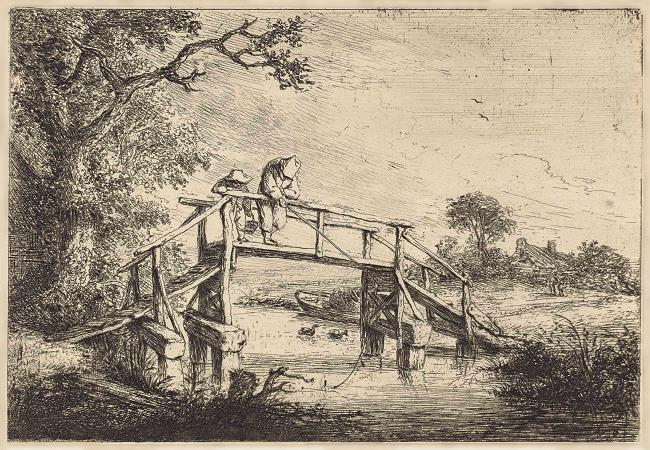

Adriaen van Ostade (1610 - 1685). Adriaen van Ostade was a Dutch Golden Age painter of genre works. According to Houbraken, he and his brother were pupils of Frans Hals and like him, spent most of their lives in Haarlem. He thought they were Lubekkers by birth, though this has since found to be false.He was the eldest son of Jan Hendricx Ostade, a weaver from the town of Ostade near Eindhoven. Although Adriaen and his brother Isaack were born in Haarlem, they adopted the name van Ostade as painters. According to the RKD, he became a pupil in 1627 of the portrait painter Frans Hals, at that time the master of Jan Miense Molenaer. In 1632 he is registered in Utrecht, but in 1634 he was back in Haarlem where he joined the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke. At twenty-six he joined a company of the civic guard at Haarlem, and at twenty-eight he married. His wife died two years later in 1640. In 1657, as a widower, he married Anna Ingels. He again became a widower in 1666. He opened a workshop and took on pupils. His notable pupils were Cornelis Pietersz Bega, Cornelis Dusart, Jan de Groot, Frans de Jongh, Michiel van Musscher, Isaac van Ostade, Evert Oudendijck, and Jan Steen. In 1662 and again in 1663 he is registered as deacon of the St. Luke guild in Haarlem. In the rampjaar he packed up his goods with the intention of fleeing to Lebeck, which is why Houbraken felt he had family there. He got as far as Amsterdam, however, when he was convinced to stay by the art collector Konstantyn Sennepart, in whose house he stayed, and where he made a series of colored drawings, that were later bought for 1300 florins by Jonas Witsen, where Houbraken saw them and fell in love with his portrayals of village life. Jonas Witsen was the man who convinced Houbraken to move to Amsterdam from Dordrecht. He had been the city secretary, and was probably his patron. His successor, Johan van Schuylenburgh, who became city secretary in 1712, was the man to whom Houbraken dedicated the first volume of his Schouburg. Ostade was the contemporary of the Flemish painters David Teniers the Younger and Adriaen Brouwer and. Like them, he spent his life in delineation of the homeliest subjects: tavern scenes, village fairs and country quarters. Between Teniers and Ostade the contrast lies in the different condition of the agricultural classes of Brabant and Holland and in the atmosphere and dwellings peculiar to each region. Brabant has more sun and more comfort; Teniers, in consequence, is silvery and sparkling, and the people he paints are fair specimens of their culture. Holland, in the vicinity of Haarlem, seems to have suffered much from war; the air is moist and hazy, and the people depicted by Ostade are short and ill-favoured, marked with adversity's stamp in feature and dress. Brouwer, who painted the peasant in his frolics and passions, brought more of the spirit of Frans Hals into his depictions than did his colleague; but the type is the same as Ostade's. During the first years of his career, Ostade tended toward the same exaggeration and frolic as his comrade, though he is distinguished from his rival by a more general use of light and shade, especially a greater concentration of light on a small surface in contrast with a broad expanse of gloom. The key of his harmonies remained for a time in the scale of greys, but his treatment is dry and careful in a style which shuns no difficulties of detail. He shows us the cottages, inside and out: vine leaves cloak the poverty of the outer walls; indoors, nothing decorates the patchwork of rafters and thatch, the tumble-down chimneys and the ladder staircases, the rustic Dutch home of those days. The greatness of Ostade lies in how often he caught the poetic side of the peasant class in spite of its coarseness. He gave the magic light of a sun-gleam to their lowly sports, their quarrels, even their quieter moods of enjoyment; he clothed the wreck of the cottages with gay vegetation. It was natural, given the tendency to effect which marked Ostade from the first, that he should have been fired by emulation to rival the masterpieces of Rembrandt. His early pictures are not so rare but that we can trace how he glided from one period to the other. Before the dispersal of the Jakob Gsell collection at Vienna in 1872, it was easy to study the steel-grey harmonies, the exaggerated caricature of his early works between 1632 and 1638. There is a picture in the Vienna Gallery of a Countryman Having his Tooth Drawn, unsigned, and painted about 1632; a Bagpiper of 1635 in the Liechtenstein Gallery at Vienna; cottage scenes of 1635 and 1636 in the museums of Karlsruhe, Darmstadt, and Dresden; and the Card Players of 1637 in the Liechtenstein palace at Vienna, making up for the loss of the Gsell collection. The same style marks most of those pieces.

more...