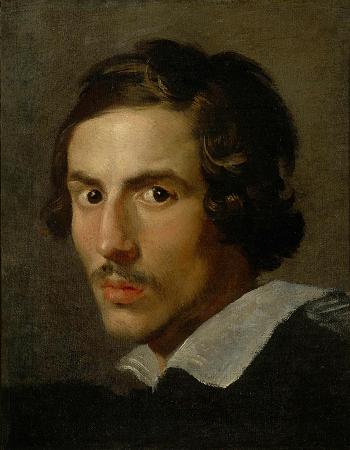

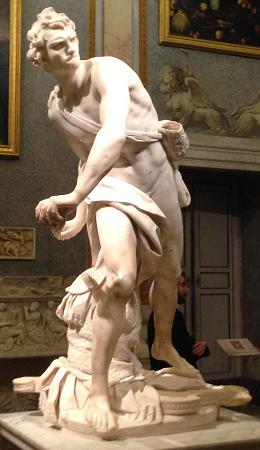

Gianlorenzo Bernini (1598 - 1680). Gian Lorenzo Bernini was an Italian sculptor and architect. While a major figure in the world of architecture, he was, also and even more prominently, the leading sculptor of his age, credited with creating the Baroque style of sculpture. As one scholar has commented, What Shakespeare is to drama, Bernini may be to sculpture: the first pan-European sculptor whose name is instantaneously identifiable with a particular manner and vision, and whose influence was inordinately powerful. In addition, he was a painter and a man of the theater: he wrote, directed and acted in plays, for which he designed stage sets and theatrical machinery. He produced designs as well for a wide variety of decorative art objects including lamps, tables, mirrors, and even coaches. As architect and city planner, he designed secular buildings, churches, chapels, and public squares, as well as massive works combining both architecture and sculpture, especially elaborate public fountains and funerary monuments and a whole series of temporary structures for funerals and festivals. His broad technical versatility, boundless compositional inventiveness and sheer skill in manipulating marble ensured that he would be considered a worthy successor of Michelangelo, far outshining other sculptors of his generation. His talent extended beyond the confines of sculpture to a consideration of the setting in which it would be situated; his ability to synthesize sculpture, painting, and architecture into a coherent conceptual and visual whole has been termed by the late art historian Irving Lavin the unity of the visual arts. Bernini was born in Naples in 1598 to Angelica Galante and Mannerist sculptor Pietro Bernini, originally from Florence. He was the sixth of their thirteen children. Gian Lorenzo Bernini was the definition of childhood genius. He was recognized as a prodigy when he was only eight years old, he was consistently encouraged by his father, Pietro. His precocity earned him the admiration and favor of powerful patrons who hailed him as the Michelangelo of his century. In 1606 his father received a papal commission and so moved from Naples to Rome, taking his entire family with him and continuing in earnest the training of his son Gian Lorenzo. Several extant works, dating from circa 1615-20, are by general scholarly consensus, collaborative efforts by both father and son: they include the Faun Teased by Putti, Boy with a Dragon, the Aldobrandini Four Seasons, and the recently discovered Bust of the Savior. Sometime after the arrival of the Bernini family in Rome, word about the great talent of the boy Gian Lorenzo got around and he soon caught the attention of Cardinal Scipione Borghese, nephew to the reigning pope, Paul V, who spoke of the boy genius to his uncle. Bernini was therefore presented before Pope Paul V, curious to see if the stories about Gian Lorenzo's talent were true. The boy improvised a sketch of Saint Paul for the marveling pope, and this was the beginning of the pope's attention on this young talent. Once he was brought to Rome, he rarely left its walls, except for a five-month stay in Paris in the service of King Louis XIV and brief trips to nearby towns, mostly for work-related reasons. Rome was Bernini's city: You are made for Rome, said Pope Urban VIII to him, and Rome for you. It was in this world of 17th-century Rome and the international religious-political power which resided there that Bernini created his greatest works. Bernini's works are therefore often characterized as perfect expressions of the spirit of the assertive, triumphal but self-defensive Counter Reformation Roman Catholic Church. Certainly Bernini was a man of his times and deeply religious, but he and his artistic production should not be reduced simply to instruments of the papacy and its political-doctrinal programs, an impression that is at times communicated by the works of the three most eminent Bernini scholars of the previous generation, Rudolf Wittkower, Howard Hibbard, and Irving Lavin. As Tomaso Montanari's recent revisionist monograph, La liberta di Bernini argues and Franco Mormando's anti-hagiographic biography, Bernini: His Life and His Rome, illustrates, Bernini and his artistic vision maintained a certain degree of freedom from the mindset and mores of Counter-Reformation Roman Catholicism. Under the patronage of the extravagantly wealthy and most powerful Cardinal Scipione Borghese, the young Bernini rapidly rose to prominence as a sculptor. Among his early works for the cardinal were decorative pieces for the garden of the Villa Borghese such as The Goat Amalthea with the Infant Jupiter and a Faun.

more...