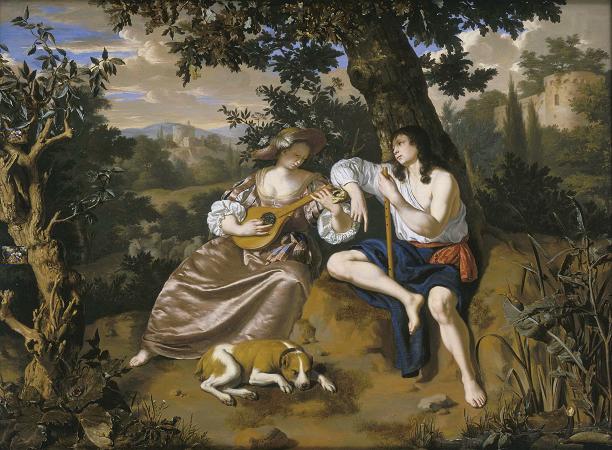

Et in Arcadia Ego (c1638). Oil on canvas. 121 x 185. Et in Arcadia ego is a 1637-38 painting by Nicolas Poussin, the leading painter of the classical French Baroque style. It depicts a pastoral scene with idealized shepherds from classical antiquity gathered around an austere tomb. It is held in the Louvre. Poussin painted two versions of the subject under the same title; his earlier version, painted in 1627, is held at Chatsworth House. An earlier treatment of the theme was painted by Guercino circa 1618-22, also titled Et in Arcadia ego. The translation of the phrase is Even in Arcadia, there am I. The usual interpretation is that I refers to Death, and Arcadia means a utopian land. It would thus be a memento mori. During Antiquity, many Greeks lived in cities close to the sea, and led an urban life. Only Arcadians, in the middle of the Peloponnese, lacked cities, were far from the sea, and led a shepherd life. Thus Arcadia symbolized pure, rural, idyllic life, far from the city. However Poussin's biographer, André Félibien, interpreted the phrase to mean that the person buried in this tomb lived in Arcadia; in other words, that the person too once enjoyed the pleasures of life on earth. This reading was common in the 18th and 19th centuries. For example, William Hazlitt wrote that Poussin describes some shepherds wandering out in a morning of the spring, and coming to a tomb with this inscription, 'I also was an Arcadian'. The former interpretation is now generally considered more likely; the ambiguity of the phrase is the subject of a famous essay by the art historian Erwin Panofsky. Either way, the sentiment was meant to set up an ironic contrast between the shadow of death and the usual idle merriment that the nymphs and swains of ancient Arcadia were thought to embody. The first appearance of a tomb with a memorial inscription amid the idyllic settings of Arcadia appears in Virgil's Eclogues V 42 ff. Virgil took the idealized Sicilian rustics that had first appeared in the Idylls of Theocritus and set them in the primitive Greek district of Arcadia. The idea was taken up anew in the circle of Lorenzo de' Medici in the 1460s and 1470s, during the Florentine Renaissance. In his pastoral work Arcadia, Jacopo Sannazaro fixed the Early Modern perception of Arcadia as a lost world of idyllic bliss, remembered in regretful dirges. The first pictorial representation of the familiar memento mori theme that was popularized in 16th-century Venice, now made more concrete and vivid by the inscription, is Guercino's version, painted between 1618 and 1622, in which the inscription gains force from the prominent presence of a skull in the foreground, beneath which the words are carved. Poussin's own first version of the painting was probably commissioned as a reworking of Guercino's version. It is in a far more Baroque style than the later version, characteristic of Poussin's early work. In the Chatsworth painting the shepherds are actively discovering the half-hidden and overgrown tomb, and are reading the inscription with curious expressions. The shepherdess, standing at the left, is posed in sexually suggestive fashion, very different from her austere counterpart in the later version. The later version has a far more geometric composition and the figures are much more contemplative. The mask-like face of the shepherdess conforms to the conventions of the Classical Greek profile. The most important difference between the two versions is that in the latter version, one of the two shepherds recognizes the shadow of his companion on the tomb and circumscribes the silhouette with his finger. According to an ancient tradition, this is the moment in which the art of painting is first discovered. Thus, the shepherd's shadow is the first image in art history. But the shadow on the tomb is also a symbol of death. The meaning of this highly intricate composition seems to be that, from prehistory onward, the discovery of art has been the creative response of humankind to the shocking fact of mortality. Thus, death's claim to rule even Arcadia is challenged by art, who must insist that she was discovered in Arcadia too, and that she is the legitimate ruler everywhere, whilst death only usurps its power. In the face of death, art's duty, indeed, her raison d'être, is to recall absent loved ones, console anxieties, evoke and reconcile conflicting emotions, surmount isolation, and facilitate the expression of the unutterable. The undated mid-eighteenth-century marble bas-relief is part of the Shepherds Monument, a garden feature at Shugborough House, Staffordshire, England. Beneath it is the cryptic Shugborough inscription, as yet undeciphered.

more...