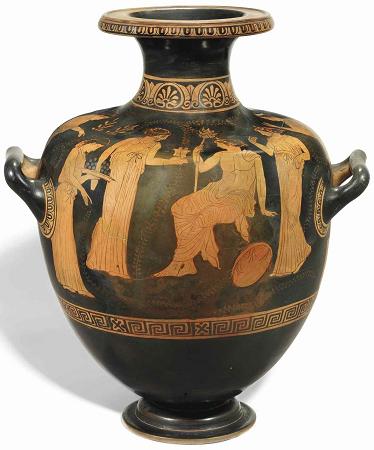

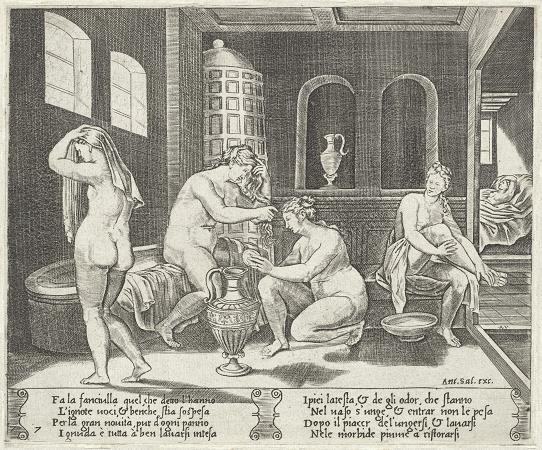

Nymph. A nymph in ancient Greek folklore is a supernatural being associated with many other minor female deities that are often associated with the air, seas, woods, water or particular locations or landforms. Different from Greek goddesses, nymphs are generally regarded as divine spirits who animate or maintain Nature for the environments where they live, and are usually depicted as beautiful, young, and graceful maidens. They were not necessarily immortal, but lived many years before they died. They are often divided into various broad subgroups, such as the Meliae, the Naiads, the Nereids, and the Oreads. Nymphs often feature in many classic works of art, literature, mythology and in fiction. Since medieval times, nymphs are sometimes popularly associated, or even confused, with the mythical or spiritual fairies. The Greek word has the primary meaning of young woman; bride, young wife but is not usually associated with deities in particular. Yet the etymology of the noun remains uncertain. The Doric and Aeolic form is. Modern usage more often applies to young women at the peak of their attractiveness, contrasting with parthenos a virgin, and generically as kore maiden, girl. The term is sometimes used by women to address each other and remains the regular Modern Greek term for bride. Nymphs were sometimes beloved by many and dwell in most specific areas related to the natural environment. e.g. mountainous regions and forests by springs or rivers. Other nymphs, mostly appeared in the shape of young maidens, were part of the retinue of a god, such as Dionysus, Hermes, or Pan, or a goddess, generally the huntress Artemis. The Greek nymphs were also spirits invariably bound to places, not unlike the Latin genius loci, and sometimes this produced complicated myths like cult of Arethusa to Sicily. In some of the works of the Greek-educated Latin poets, the nymphs gradually absorbed into their ranks the indigenous Italian divinities of springs and streams, while the Lymphae, Italian water-goddesses, owing to the accidental similarity of their names, could be identified with the Greek Nymphae. The classical mythologies of the Roman poets were unlikely to have affected the rites and cults of individual nymphs venerated by country people in the springs and clefts of Latium. Among the Roman literate class, their sphere of influence was restricted, and they appear almost exclusively as divinities of the watery element. The ancient Greek belief in nymphs survived in many parts of the country into the early years of the twentieth century, when they were usually known as nereids. Often nymphs tended to frequent areas distant from humans but could be encountered by lone travelers outside the village, where their music might be heard, and the traveler could spy on their dancing or bathing in a stream or pool, either during the noon heat or in the middle of the night. They might appear in a whirlwind. Such encounters could be dangerous, bringing dumbness, besotted infatuation, madness or stroke to the unfortunate human. When parents believed their child to be nereid-struck, they would pray to Saint Artemidos. Nymphs often feature or are depicted in many classic works across art, literature, mythology and in fiction. They are often associated with the medieval romances or Renaissance literature of the elusive mythical or spiritual fairies or elves. Fairies are believed to have mixed openly with the classical nymphs and satyrs, or sometimes even replacing the roles of the classical nymphs. A motif that entered European art during the Renaissance was the idea of a statue of a nymph sleeping in a grotto or spring. This motif supposedly came from an Italian report of a Roman sculpture of a nymph at a fountain above the River Danube. The report, and an accompanying poem supposedly on the fountain describing the sleeping nymph, are now generally concluded to be a fifteenth-century forgery, but the motif proved influential among artists and landscape gardeners for several centuries after, with copies seen at neoclassical gardens such as the grotto at Stourhead.

more...