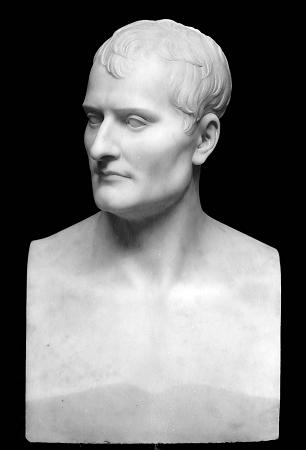

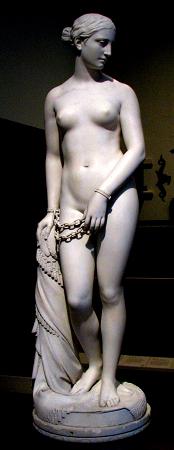

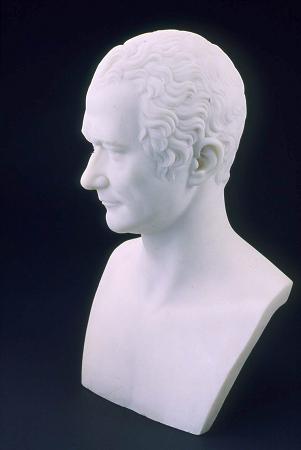

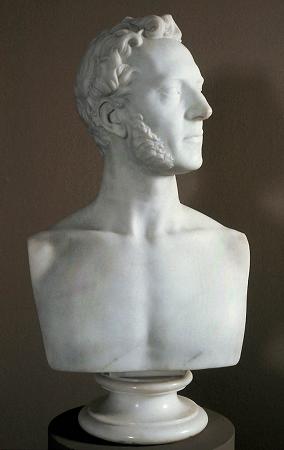

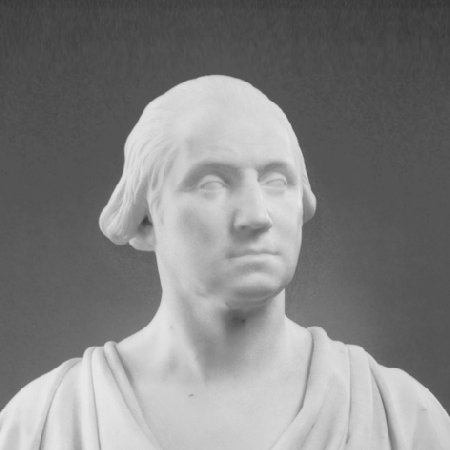

Horatio Greenough (1805 - 1852). Horatio Greenough was an American sculptor best known for his United States government commissions The Rescue and George Washington. The son of Elizabeth and David Greenough, he was born in Boston on September 6, 1805, into a home with ethics for honesty and emphasis on good education. Horatio showed an early interest in artistic and mechanical hobbies. Particularly attracted to chalk, around the age of 12 he made a chalk statue of William Penn, known as his earliest work of record. Horatio also experimented with clay, which medium he learned from Solomon Willard. He also learned how to carve with marble under instruction from Alpheus Cary. Horatio seemed to have a natural talent for art, yet his father wasn't fond of the idea of this as a career for Horatio. In 1814 Horatio Greenough enrolled at Phillips Academy, Andover, and in 1821 he entered Harvard University. There he found a passion in works of antiquity and devoted much of his time to reading literature and works of art. With a plan to study abroad, he learned Italian and French, but also still studied anatomy and kept modeling sculptures. While attending Harvard he came across his first crucial influence. Washington Allston was more than a mentor, but a close friend who enlightened and inspired Horatio. He even molded a bust of Washington. Before graduating from Harvard, he sailed to Rome to study art where he met the painter Robert W. Weir, while living on Via Gregoriana. These two became close friends and studied together the Renaissance and works of antiquity. Favorites of theirs were the Laocoon group of the Vatican structure galleries and the Apollo Belvedere. During Horatio's time spent in Rome, he created many busts, as well as a full-size statue of the Dead Abel, and a portrait of himself. He returned to Boston in May 1827 with Weir, after recovering an attack of malaria. He modeled busts such as Josiah Quincy, president of Harvard, Samuel Appleton and John Jacob Astor. In an attempt to establish a greater reputation he sought out to make a portrait of President John Quincy Adams. His plan worked as he displayed a style of naturalism in this piece as he did in many other works. In 1828 he established a studio in Florence. Although Greenough was generally healthy, in December 1852 he contracted a severe fever. On December 18, after two weeks of this high fever he died at the age of 47 in Somerville, near Boston. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1843. His sketchbook is held in the Archives of American Art. In 1828 he was elected into the National Academy of Design as an Honorary Academician. His younger brother was the sculptor Richard Saltonstall Greenough. Horatio's son, biologist Horatio S. Greenough, proposed a stereo microscope design to Ernst Abbe of Carl Zeiss AG circa 1896 in Paris that led to the first commercial stereomicroscope. The younger Greenough's design, originally intended for dissection, is still widely used in the optics industry. His sculptures reflected truth and reality, but also ancient classical aesthetic ideals learned from Washington Allston. Many of Greenough's works were done in Florence, Italy where he spent most of his professional life. His sculpture The Rescue and his over-life-size George Washington both derived from United States government commissions. Some of his other most famous and important sculptures include James Fenimore Cooper, Castor and Pollux, and Marquis de Lafayette. A prolific draftsman, a selection of his drawings were displayed in 1999 in the exhibition Horatio Greenough: An American Sculptor's Drawings, at the Middlebury College Museum of Art. His works are in the Art Institute of Chicago, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Fine Arts, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Probably Greenough's most enduring achievements are his essays on art. Here Greenough repeatedly criticized contemporary American architecture for its imitation of European historical building styles, wrote enthusiastically about the beauty of animal bodies, of machine constructions, and of ship design, and argued that as to architecture, formal solutions were inherent in the functions of the building; in this he anticipated the later functionalist thinking. The origin of the phrase form follows function is often, but wrongly, ascribed to Greenough, although the theory of inherent forms, of which the phrase is a fitting summary, informs all of Greenough's writing on art, design, and architecture. The phrase itself was coined by the architect Louis Sullivan, Greenough's much younger compatriot, in 1896, some fifty years after Greenough's death.

more...