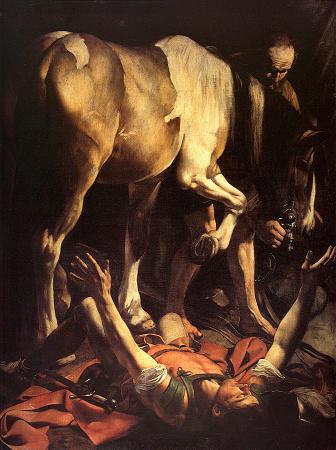

Santa Maria del Popolo. The Parish Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo is a titular church and a minor basilica in Rome run by the Augustinian order. It stands on the north side of Piazza del Popolo, one of the most famous squares in the city. The church is hemmed in between the Pincian Hill and Porta del Popolo, one of the gates in the Aurelian Wall as well as the starting point of Via Flaminia, the most important route from the north. Its location made the basilica the first church for the majority of travellers entering the city. The church contains works by several famous artists, such as Raphael, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Caravaggio, Alessandro Algardi, Pinturicchio, Andrea Bregno, Guillaume de Marcillat and Donato Bramante. The well-known foundation legend of Santa Maria del Popolo revolves around the evil memory of Emperor Nero and Pope Paschal II cleansing the area from this malicious legacy. As the story goes, after his suicide Nero was buried in the mausoleum of his paternal family, the Domitii Ahenobarbi, at the foot of the Pincian Hill. The sepulchre was later buried under a landslide and on its ruins grew a huge walnut tree that was so tall and sublime that no other plant exceeded it in any ways. The tree soon became the haunt for a multitude of vicious demons harassing the inhabitants of the area and also the travelers arriving in the city from the north through Porta Flaminia: some were being frightened, possessed, cruelly beaten and injured, others almost strangled, or miserably killed. As the demons endangered an important access road of the city and also upset the entire population, the newly elected pontiff, Paschal II, was seriously concerned. He saw the flock of Christ committed to his watch, becoming prey to the infernal wolves. The Pope fasted and prayed for three days and at the end of that period, exhausted, he dreamt of the Blessed Virgin Mary, who gave him detailed instructions on how to free the city from the demonic scourge. On the Thursday after the Third Sunday of Lent in 1099, the Pope organised the entire clergy and populace of Rome in one, impressive procession that, with the crucifix at its head, went along the urban stretch of the Via Flaminia until it reached the infested place. There, Paschal II performed the rite of exorcism and then struck the walnut tree with a determined blow to its root, causing the evil spirits to burst forth, madly screaming. When the whole tree was removed, the remains of Nero were discovered among the ruins; the Pope ordered these thrown into the Tiber. Finally liberated from the demons, that corner of Rome could be devoted to Christian worship. Paschal II, to the sound of hymns, placed the first stone of an altar at the former site of the walnut tree. This was incorporated into a simple chapel which was completed in three days. The construction was celebrated with particular solemnity: the Pope consecrated the small sanctuary in the presence of a large crowd, accompanied by ten cardinals, four archbishops, ten bishops and other prelates. He also granted the chapel many relics and dedicated it to the Virgin Mary. The legend was recounted by an Augustinian friar, Giacomo Alberici in his treatise about the Church of Santa Maria del Popolo which was published in Rome in 1599 and translated into Italian the next year. Another Augustinian, Ambrogio Landucci rehashed the same story in his book about the origins of the basilica in 1646. The legend has been retold several times ever since with slight changes in collections of Roman curiosities, scientific literature and guidebooks. An example of the variations could be found in Ottavio Panciroli's book which claimed that the demons inhabiting the tree took the form of black crows. It is not known how far the tradition goes back but in 1726 in the archive of Santa Maria del Popolo there was a catalogue of the holy relics of the church written in 1426 which contained a version of the miracle of the walnut tree. This was allegedly copied from an even more ancient tabella at the main altar. In the 15th century the story was already popular enough to be recounted by various German sources like Nikolaus Muffel's Description of Rome or The Pilgrimage of Arnold Von Harff. The factual basis of the legend is weak. Nero was indeed buried in the mausoleum of his paternal family, but Suetonius in his Life of Nero writes that the family tomb of the Domitii on the summit of the Hill of Gardens, which is visible from the Campus Martius. The location of the mausoleum was therefore somewhere on the higher north-west slopes of the Pincian Hill and certainly not at the foot of it where the church stands.

more...