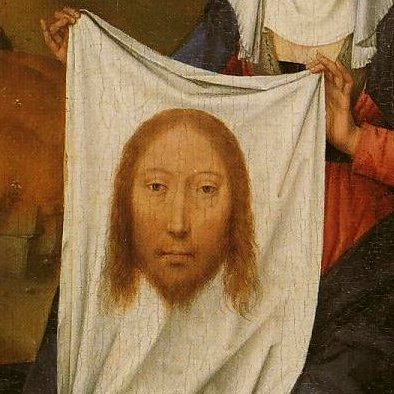

Diptych. A diptych is a work of art that consists of two sections that are hinged, allowing them to be folded shut. The Wilton Diptych (c1430) exemplifies the International Gothic style. The left panel features King Richard II kneeling in prayer, while the right panel depicts the Virgin Mary and Child. The Merode Altarpiece (c1430) by Robert Campin is also in International Gothic style. The left panel depicts the Annunciation, and the right panel portrays the kneeling donor figures. The Arnolfini Portrait (1434) by Jan van Eyck features a convex mirror in the background reflecting the artist. The Diptych of Philip de Croy with The Virgin and Child consists of a pair of small oil-on-oak panels painted c1460 by Rogier van der Weyden. The Bembo Diptych (c1482) by Hans Memlimg has Saint John Baptest on the left and Saint Veronica with the Sudarium on the right. Diptychs have been used in various forms of art, including painting, sculpture, and photography. The panels of a diptych may be the same size or different sizes, and they may be arranged horizontally or vertically. The Guevara diptych is a two-part devotional artwork likely depicts a Spanish nobleman, Diego de Guevara, alongside a separate panel of the Virgin Mary and baby Jesus. A diptych is any object with two flat plates attached at a hinge. The standard notebook and school exercise book of the ancient world was a diptych consisting of a pair of such plates that contained a recessed space filled with wax. Writing was accomplished by scratching the wax surface with a stylus. When the notes were no longer needed, the wax could be slightly heated and then smoothed to allow reuse. Ordinary versions had wooden frames, but more luxurious diptychs were crafted with more expensive materials. In Late Antiquity, ivory notebook diptychs with covers carved in low relief on the outer faces were a significant art-form: the consular diptych was made to celebrate an individual's becoming Roman consul, when they seem to have been made in sets and distributed by the new consul to friends and followers. Others may have been made to celebrate a wedding, or, perhaps like the Poet and Muse diptych at Monza, simply commissioned for private use. Some of the most important surviving works of the Late Roman Empire are diptychs, of which some dozens survive, preserved in some instances by being reversed and re-used as book covers. The largest surviving Byzantine ivory panel, is a leaf from a diptych in the Justinian court manner of c. 525-50, which features an archangel. From the Middle Ages many panel paintings took the diptych form, as small portable works for personal use; Eastern Orthodox ones may be called travelling icons. Although the tryptych form was more common, there were also ivory diptychs with religious scenes carved in relief, a form found first in Byzantine art before becoming very popular in the Gothic period in the West, where they were mainly produced in Paris. These suited the mobile lives of medieval elites. The ivories tended to have scenes in several registers crowded with small figures. The paintings generally had single subjects on a panel, the two matching, though by the 15th century one panel might contain a portrait head of the owner or commissioner, with the Virgin or another religious subject on the other side.

more...