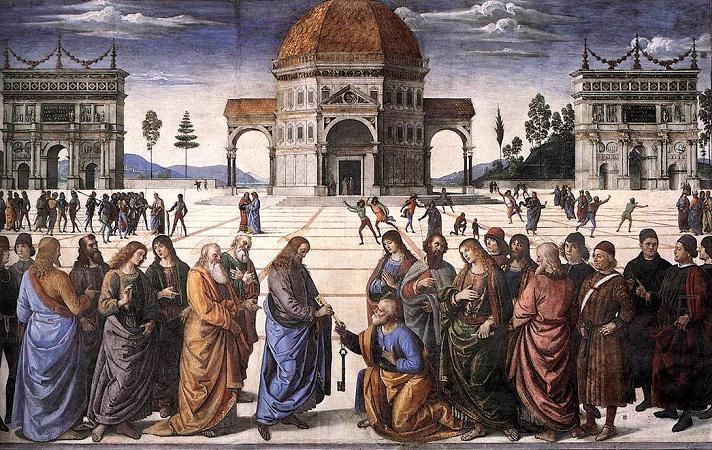

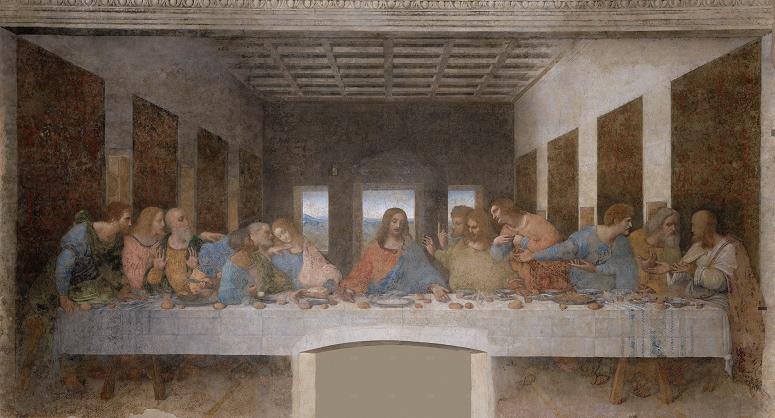

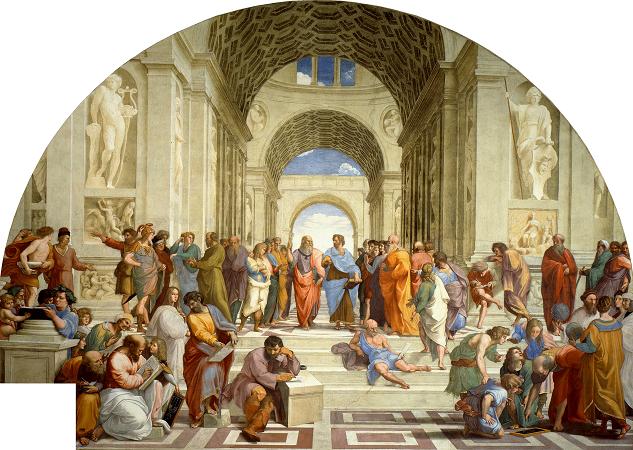

Fresco. Fresco is a painting technique in which pigments are applied to wet plaster, allowing the colors to become an integral part of the wall or ceiling surface as the plaster dries. Some of the most famous frescos in the world include Michelangelo's ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City, which features scenes from the Old Testament, including the iconic image of God reaching out to touch Adam. Another famous example is Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper, which depicts Jesus and his disciples at the moment when Jesus announces that one of them will betray him. This fresco is located in the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Italy. Other artists who worked in the fresco medium include Giotto, Raphael, and Diego Rivera. Giotto's frescos in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy, are considered some of the most important works of the early Renaissance, while Raphael's frescos in the Vatican Palace are renowned for their beauty and technical skill. Diego Rivera, a Mexican artist who worked in the 20th century, is known for his large-scale frescos that depict scenes of Mexican history and culture. While fresco is an ancient technique, it is still used by contemporary artists today. One notable example is the American artist Mark Rothko, who created a series of large-scale frescos for the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas. These works, which feature abstract fields of color, are considered some of the most important examples of modern art. Water is used as the vehicle for the dry-powder pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plaster, the painting becomes an integral part of the wall. The word fresco is derived from the Italian adjective fresco meaning fresh, and may thus be contrasted with fresco-secco or secco mural painting techniques, which are applied to dried plaster, to supplement painting in fresco. The fresco technique has been employed since antiquity and is closely associated with Italian Renaissance painting. Buon fresco pigment is mixed with room temperature water and is used on a thin layer of wet, fresh plaster, called the intonaco. Because of the chemical makeup of the plaster, a binder is not required, as the pigment mixed solely with the water will sink into the intonaco, which itself becomes the medium holding the pigment. In painting buon fresco, a rough underlayer called the arriccio is added to the whole area to be painted and allowed to dry for some days. Many artists sketched their compositions on this underlayer, which would never be seen, in a red pigment called sinopia, a name also used to refer to these under-paintings. Later,new techniques for transferring paper drawings to the wall were developed. The main lines of a drawing made on paper were pricked over with a point, the paper held against the wall, and a bag of soot banged on them to produce black dots along the lines. If the painting was to be done over an existing fresco, the surface would be roughened to provide better adhesion. On the day of painting, the intonaco, a thinner, smooth layer of fine plaster was added to the amount of wall that was expected to be completed that day, sometimes matching the contours of the figures or the landscape, but more often just starting from the top of the composition. This area is called the giornata, and the different day stages can usually be seen in a large fresco, by a sort of seam that separates one from the next. Buon frescoes are difficult to create because of the deadline associated with the drying plaster. Generally, a layer of plaster will require ten to twelve hours to dry; ideally, an artist would begin to paint after one hour and continue until two hours before the drying time, giving seven to nine hours' working time.

more...