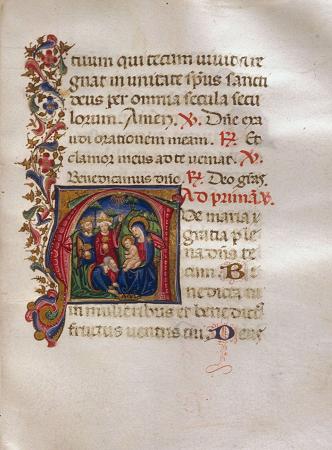

Adoration of Magi. The Adoration of the Magi or Adoration of the Kings is the name traditionally given to the subject in the Nativity of Jesus in art in which the three Magi, represented as kings, especially in the West, having found Jesus by following a star, lay before him gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh, and worship him. It is related in the Bible by Matthew 2:11: On entering the house, they saw the child with Mary his mother; and they knelt down and paid him homage. Then, opening their treasure chests, they offered him gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. And having been warned in a dream not to return to Herod, they left for their own country by another path. Christian iconography has considerably expanded the bare account of the Biblical Magi given in the second chapter of the Gospel of Matthew and used it to press the point that Jesus was recognized, from his earliest infancy, as king of the earth. The scene was often used to represent the Nativity, one of the most indispensable episodes in cycles of the Life of the Virgin as well as the Life of Christ. In the church calendar, the event is commemorated in Western Christianity as the Feast of the Epiphany. The Orthodox Church commemorates the Adoration of the Magi on the Feast of the Nativity. The term is anglicized from the Vulgate Latin section title for this passage: A Magis adoratur. In the earliest depictions, the Magi are shown wearing Persian dress of trousers and Phrygian caps, usually in profile, advancing in step with their gifts held out before them. These images adapt Late Antique poses for barbarians submitting to an Emperor, and presenting golden wreaths, and indeed relate to images of tribute-bearers from various Mediterranean and ancient Near Eastern cultures going back many centuries. The earliest are from catacomb paintings and sarcophagus reliefs of the 4th century. Crowns are first seen in the 10th century, mostly in the West, where their dress had by that time lost any Oriental flavour in most cases.The standard Byzantine depiction of the Nativity included the journey or arrival of the mounted Magi in the background, but not them presenting their gifts, until the post-Byzantine period, when the western depiction was often adapted to an icon style. Later Byzantine images often show small pill-box like hats, whose significance is disputed. The Magi are usually shown as the same age until about this period, but then the idea of depicting the three ages of man is introduced: a particularly beautiful example is seen on the facade of the cathedral of Orvieto. Occasionally from the 12th century, and very often in Northern Europe from the 15th, the Magi are also made to represent the three known parts of the world: Balthasar is very commonly cast as a young African or Moor, and old Caspar is given Oriental features or, more often, dress. Melchior represents Europe and middle age. From the 14th century onward, large retinues are often shown, the gifts are contained in spectacular pieces of goldsmith work, and the Magi's clothes are given increasing attention. By the 15th century, the Adoration of the Magi is often a bravura piece in which the artist can display their handling of complex, crowded scenes involving horses and camels, but also their rendering of varied textures: the silk, fur, jewels and gold of the Kings set against the wood of the stable, the straw of Jesus's manger and the rough clothing of Joseph and the shepherds. The scene often includes a fair diversity of animals as well: the ox and ass from the Nativity scene are usually there, but also the horses, camels, dogs, and falcons of the kings and their retinue, and sometimes other animals, such as birds in the rafters of the stable. From the 15th century onwards, the Adoration of the Magi is quite often conflated with the Adoration of the Shepherds from the account in the Gospel of Luke, an opportunity to bring in yet more human and animal diversity; in some compositions, the two scenes are contrasted or set as pendants to the central scene, usually a Nativity. The adoration of the Magi at the crib is the usual subject, but their arrival, called the Procession of the Magi, is often shown in the distant background of a Nativity scene, or as a separate subject, for example in the Magi Chapel frescos by Benozzo Gozzoli in the Palazzo Medici Riccardi, Florence. Other subjects include the Journey of the Magi, where they and perhaps their retinue are the only figures, usually shown following the Star of Bethlehem, and there are relatively uncommon scenes of their meeting with Herod and the Dream of the Magi.

more...