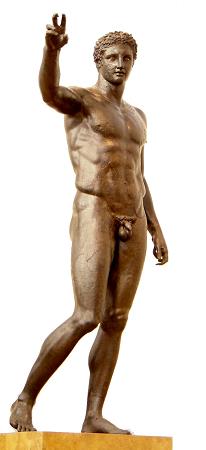

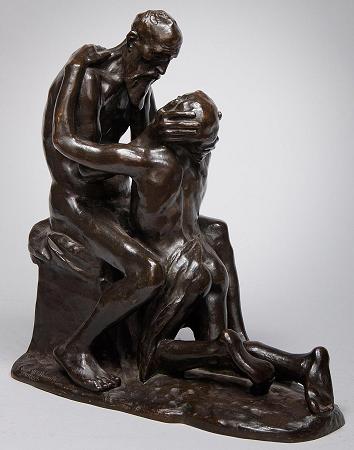

Bronze. Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, and often with the addition of tin and other metals and non-metals. It has been used as an art material for thousands of years, primarily in sculpture and casting. Its durability, malleability, and resistance to corrosion make it an ideal choice for creating both large and intricate works. Artists often use the lost-wax casting technique, where a model is created in wax, encased in a mold, and then melted away to leave a hollow space for pouring molten bronze. This method allows for fine details and complex shapes. In addition to sculpture, bronze has been used for decorative objects, medals, and functional items, such as handles and fixtures. The metal can be polished to a shiny finish or patinated to develop a range of colors and textures over time. Bronze has significant historical and cultural importance, often associated with notable artworks from ancient civilizations, such as the famous Greek sculptures and the statues of deities. Additions produce a range of alloys that may be harder than copper alone, or have other useful properties, such as strength, ductility, or machinability. The archaeological period in which bronze was the hardest metal in widespread use is known as the Bronze Age. The beginning of the Bronze Age in western Eurasia and India is conventionally dated to the mid-4th millennium BC, and to the early 2nd millennium BC in China; elsewhere it gradually spread across regions. The Bronze Age was followed by the Iron Age starting about 1300 BC and reaching most of Eurasia by about 500 BC, although bronze continued to be much more widely used than it is in modern times. Because historical artworks were often made of brasses and bronzes of different metallic compositions, modern museum and scholarly descriptions of older artworks increasingly use the generalized term copper alloy instead of the names of individual alloys. This is done to prevent database searches from failing merely because of errors or disagreements in the naming of historic copper alloys. Houmuwu ding, the heaviest Chinese ritual bronze ever found; 1300-1046 BC; National Museum of China. Roman bronze nails with magical signs and inscriptions, 3rd-4th century AD. The discovery of bronze enabled people to create metal objects that were harder and more durable than previously possible. Bronze tools, weapons, armor, and building materials such as decorative tiles were harder and more durable than their stone and copper predecessors. Initially, bronze was made out of copper and arsenic or from naturally or artificially mixed ores of those metals, forming arsenic bronze. The earliest known arsenic-copper-alloy artifacts come from a Yahya Culture site, at Tal-i-Iblis on the Iranian plateau, and were smelted from native arsenical copper and copper-arsenides, such as algodonite and domeykite. The earliest tin-copper-alloy artifact has been dated to c. Other early examples date to the late 4th millennium BC in Egypt, Susa and some ancient sites in China, Luristan, Tepe Sialk, Mundigak, and Mesopotamia. Tin bronze was superior to arsenic bronze in that the alloying process could be more easily controlled, and the resulting alloy was stronger and easier to cast. Also, unlike those of arsenic, metallic tin and the fumes from tin refining are not toxic. Tin became the major non-copper ingredient of bronze in the late 3rd millennium BC. Ores of copper and the far rarer tin are not often found together, so serious bronze work has always involved trade with other regions. Tin sources and trade in ancient times had a major influence on the development of cultures. In Europe, a major source of tin was the British deposits of ore in Cornwall, which were traded as far as Phoenicia in the eastern Mediterranean. In many parts of the world, large hoards of bronze artifacts are found, suggesting that bronze also represented a store of value and an indicator of social status. In Europe, large hoards of bronze tools, typically socketed axes, are found, which mostly show no signs of wear.

more...