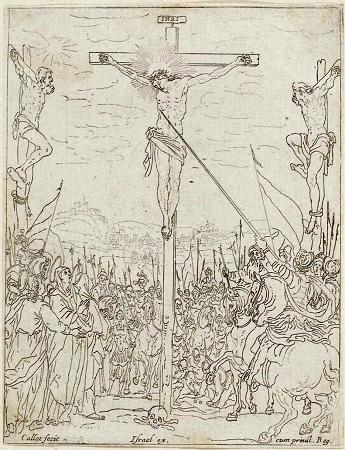

Jacques Callot (1592 - 1635). Jacques Callot was a baroque printmaker and draftsman from the Duchy of Lorraine. He is an important person in the development of the old master print. He made more than 1,400 etchings that chronicled the life of his period, featuring soldiers, clowns, drunkards, Gypsies, beggars, as well as court life. He also etched many religious and military images, and many prints featured extensive landscapes in their background. Callot was born and died in Nancy, the capital of Lorraine, now in France. He came from an important family, and he often describes himself as having noble status in the inscriptions to his prints. At the age of fifteen he was apprenticed to a goldsmith, but soon afterward travelled to Rome where he learned engraving from an expatriate Frenchman, Philippe Thomassin. He probably then studied etching with Antonio Tempesta in Florence, where he lived from 1612 to 1621. More than 2,000 preparatory drawings and studies for prints survive, but no paintings by him are known, and he probably never trained as a painter. During his period in Florence he became an independent master, and worked often for the Medici court. After the death of Cosimo II de' Medici during 1621, he returned to Nancy where he lived for the rest of his life, visiting Paris and the Netherlands later during the decade. He was commissioned by the courts of Lorraine, France and Spain, and by publishers, mostly in Paris. Although he remained in Nancy, his prints were distributed widely through Europe; Rembrandt was a keen collector of them. His technique was exceptional, and was helped by important technical advances he made. He developed the echoppe, a type of etching-needle with a slanting oval section at the end, which enabled etchers to create a swelling line, as engravers were able to do. He also seems to have been responsible for an improved recipe for the etching ground that coated the plate and was removed to form the image, using lute-makers varnish rather than a wax-based formula. This enabled lines to be etched more deeply, prolonging the life of the plate in printing, and also greatly reducing the risk of foul-biting, such that acid gets through the ground to the plate where it is not intended to, producing spots or blotches on the image. Previously the risk of foul-biting had always been present, preventing an engraver from investing too much time on a single plate that risked being ruined by foul-biting. Now etchers could do the very detailed work that was previously the monopoly of engravers, and Callot made good use of the new possibilities. He also made more extensive and sophisticated use of multiple stoppings-out than previous etchers had done. This is the technique of letting the acid dissolve lightly over the whole plate, then stopping-out those parts of the work which the artist wishes to keep shallow by covering them with ground before bathing the plate in acid again. He achieved unprecedented subtlety in effects of distance and light and shade by careful control of this process. Most of his prints were relatively small-as much as about six inches or 15 cm on their longest dimension. One of his devotees, the Parisian Abraham Bosse spread Callot's innovations all over Europe with the first published manual of etching, which was translated into Italian, Dutch, German and English. His most famous prints are his two series of prints each on the Miseries and Misfortunes of War. These are known as Les Grandes Miseres de la guerre, consisting of 18 prints published during 1633, and the earlier and incomplete Les Petites Miseres, referring to their sizes, large and small. These images show soldiers pillaging and burning their way through towns, country and convents, before being variously arrested and executed by their superiors, lynched by peasants, or surviving to live as crippled beggars. At the end the generals are rewarded by their monarch. During 1633, the year the larger set was published, Lorraine had been invaded by the French during the Thirty Years' War and Callot's artwork is still noted with Francisco Goya's Los Desastres de la Guerra, which was influenced by Callot-, as among the most powerful artistic statements of the inhumanity of war. Callot's series of Grotesque Dwarves were to inspire Derby porcelain and other companies to create pottery figures known as Mansion House Dwarves or Grotesque Dwarves. The former title comes from a father and son who were paid to wander around the Mansion House in London wearing oversized hats that contained advertisements. Varie Figure Gobbi-Series of 21 etchings, 1616.

more...