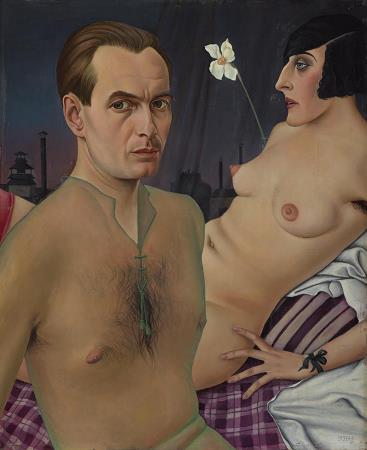

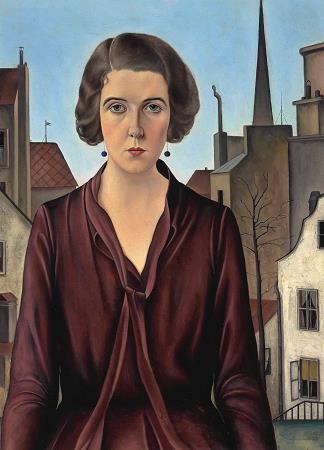

New Objectivity. New Objectivity was a movement in German art that emerged as a distinct reaction to the emotional intensity of earlier movements like Expressionism, prioritizing a clearer, more realistic representation of subjects. This shift resulted in paintings that often featured detailed, objective depictions, starkly contrasting with the abstract and emotive styles that preceded them. In relation to current political events, particularly the disillusionment following World War I, New Objectivity artists often infused their work with social commentary, reflecting the tensions and anxieties of a rapidly changing society. This focus on realism and the human condition laid the groundwork for later movements, influencing styles such as Photorealism and Contemporary Realism, which similarly emphasize detail and clarity while often engaging with modern themes and societal issues. The term was coined by Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub, the director of the Kunsthalle in Mannheim, who used it as the title of an art exhibition staged in 1925 to showcase artists who were working in a post-expressionist spirit. As these artists, who included Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, George Grosz, Christian Schad, Rudolf Schlichter and Jeanne Mammen, rejected the self-involvement and romantic longings of the expressionists, Weimar intellectuals in general made a call to arms for public collaboration, engagement, and rejection of romantic idealism. Although principally describing a tendency in German painting, the term took a life of its own and came to characterize the attitude of public life in Weimar Germany as well as the art, literature, music, and architecture created to adapt to it. Rather than some goal of philosophical objectivity, it was meant to imply a turn towards practical engagement with the world, an all-business attitude, understood by Germans as intrinsically American. The movement essentially ended in 1933 with the end of the Weimar Republic and the beginning of the Nazi dictatorship. Crockett argues against the view implied by the translation of New Resignation, which he says is a popular misunderstanding of the attitude it describes. The idea that it conveys resignation comes from the notion that the age of great socialist revolutions was over and that the left-leaning intellectuals who were living in Germany at the time wanted to adapt themselves to the social order represented in the Weimar Republic. Crockett says the art of the Neue Sachlichkeit was meant to be more forward in political action than the modes of Expressionism it was turning against: The Neue Sachlichkeit is Americanism, cult of the objective, the hard fact, the predilection for functional work, professional conscientiousness, and usefulness.

more...