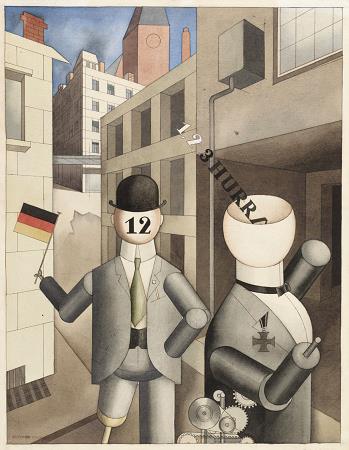

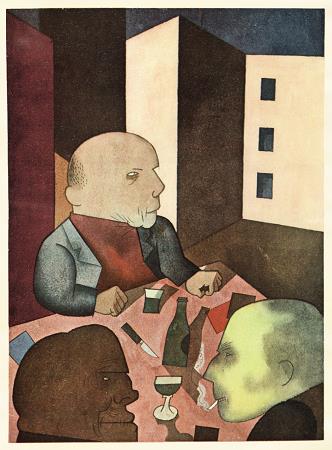

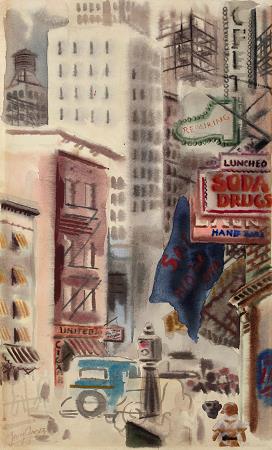

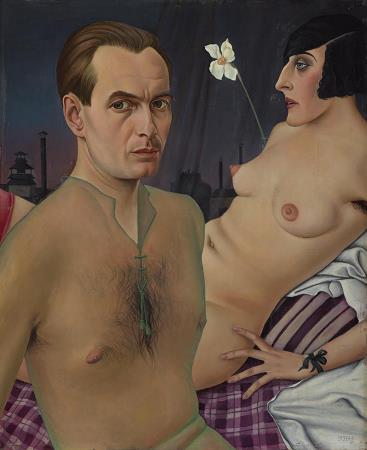

George Grosz (1893 - 1959). George Grosz was a German artist known especially for his caricatural drawings and paintings of Berlin life in the 1920s. He was a prominent member of the Berlin Dada and New Objectivity groups during the Weimar Republic. He emigrated to the United States in 1933, and became a naturalized citizen in 1938. Abandoning the style and subject matter of his earlier work, he exhibited regularly and taught for many years at the Art Students League of New York. In 1959 he returned to Berlin, where he died shortly afterwards. Made in Germany, by George Grosz, drawn in pen 1919, photo-lithograph published 1920 in the portfolio God with us. Sheet 48.3 x 39.1 cm. In the collection of the MoMA Grosz was born Georg Ehrenfried Groß in Berlin, Germany, the third child of a pub owner. His parents were devoutly Lutheran. Grosz grew up in the Pomeranian town of Stolp. After his father's death in 1900, he moved to the Wedding district of Berlin with his mother and sisters. At the urging of his cousin, the young Grosz began attending a weekly drawing class taught by a local painter named Grot. Grosz developed his skills further by drawing meticulous copies of the drinking scenes of Eduard von Grützner, and by drawing imaginary battle scenes. He was expelled from school in 1908 for insubordination. From 1909 to 1911, he studied at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts, where his teachers were Richard Müller, Robert Sterl, Raphael Wehle, and Osmar Schindler. His first published drawing was in the satirical magazine Ulk in 1910. From 1912 until 1917 he studied at the Berlin College of Arts and Crafts under Emil Orlik. He began painting in oils in 1912. George Grosz, Daum marries her pedantic automaton George in May 1920, John Heartfield is very glad of it, Berlinische Galerie In November 1914 Grosz volunteered for military service, in the hope that by thus preempting conscription he would avoid being sent to the front. He was given a discharge after hospitalization for sinusitis in 1915. In 1916 he changed the spelling of his name to de-Germanise and internationalise his name-thus Georg became George, while in his surname he replaced the German ß with its phonetic equivalent sz. He did this as a protest against German nationalism and out of a romantic enthusiasm for America-a legacy of his early reading of the books of James Fenimore Cooper, Bret Harte and Karl May-that he retained for the rest of his life. His artist friend and collaborator Helmut Herzfeld likewise changed his name to John Heartfield at the same time. In January 1917 Grosz was drafted for service, but in May he was discharged as permanently unfit. George Grosz, Republican Automatons, 1920, watercolor on paper, Museum of Modern Art, New York Following the November Revolution in the last months of 1918, Grosz joined the Spartacist League, which was renamed the Communist Party of Germany in December 1918. He was arrested during the Spartakus uprising in January 1919, but escaped using fake identification documents. In 1920 he married Eva Peters. In the same year he published a collection of his drawings, titled Gott mit uns, a satire on German society. Grosz was accused of insulting the army, which resulted in a 300 German Mark fine and the confiscation of the plates used to print the album. He also organised and exhibited at the First International Dada Fair. In 1922 Grosz traveled to Russia with the Danish writer Martin Andersen Nexø. Upon their arrival in Murmansk they were briefly arrested as spies; after their credentials were approved, they were allowed to continue their journey. He met with several Bolshevik leaders such as Grigory Zinoviev, Karl Radek, and Vladimir Lenin. He went with Arthur Holitscher to meet Anatoly Lunacharsky with whom he discussed Proletkult. He rejected the concept of proletarian culture, arguing that the term proletarian meant uneducated and uncultured. He regarded artistic talent as a gift of the muses, which a person may be lucky enough to be born with. There he also met the Constructivist artist Vladimir Tatlin. Grosz's six-month stay in the Soviet Union left him unimpressed by what he had seen. He ended his membership in the KPD in 1923, although his political positions were little changed. According to Grosz's son Martin Grosz, during the 1920s Nazi officers visited Grosz's studio looking for him, but because he was wearing a working man's apron Grosz was able to pass himself off as a handyman and avoid being taken into custody. His work was also part of the painting event in the art competition at the 1928 Summer Olympics. On December 10, 1928 he and his publisher Wieland Herzfelde were prosecuted and fined under charges of blasphemy and sacrilege for publishing two anticlerical drawings in his portfolio Hintergrund

more...