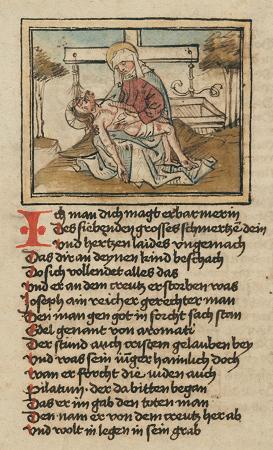

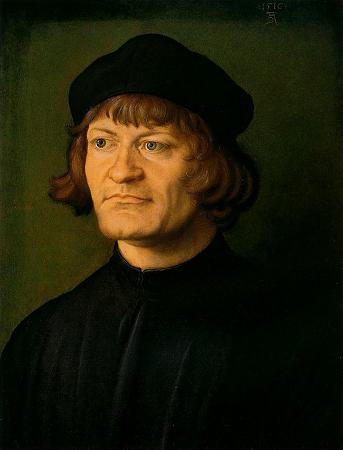

Parchment. Parchment is a writing material made from specially prepared untanned skins of animals, primarily sheep, calves, and goats. It has been used as a writing medium for over two millennia. Vellum is a finer quality parchment made from the skins of young animals such as lambs and young calves. It may be called animal membrane by libraries and museums that wish to avoid distinguishing between parchment and the more-restricted term vellum. The word is derived from the Koine Greek city name, Pergamum in Anatolia, where parchment was supposedly first developed around the second century BCE, probably as a substitute for papyrus which was then becoming less easily available. Today the term parchment is often used in non-technical contexts to refer to any animal skin, particularly goat, sheep or cow, that has been scraped or dried under tension. The term originally referred only to the skin of sheep and, occasionally, goats. The equivalent material made from calfskin, which was of finer quality, was known as vellum; while the finest of all was uterine vellum, taken from a calf foetus or stillborn calf. Some authorities have sought to observe these distinctions strictly: for example, lexicographer Samuel Johnson in 1755, and master calligrapher Edward Johnston in 1906. However, when old books and documents are encountered it may be difficult, without scientific analysis, to determine the precise animal origin of a skin, either in terms of its species or in terms of the animal's age. In practice, therefore, there has long been considerable blurring of the boundaries between the different terms. In 1519, William Horman wrote in his Vulgaria: That stouffe that we wrytte upon, and is made of beestis skynnes, is somtyme called parchement, somtyme velem, somtyme abortyve, somtyme membraan. In Shakespeare's Hamlet the following exchange occurs: Hamlet. Is not parchment made of sheepskins? Horatio. Ay, my lord, and of calves' skins too. Lee Ustick, writing in 1936, commented: To-day the distinction, among collectors of manuscripts, is that vellum is a highly refined form of skin, parchment a cruder form, usually thick, harsh, less highly polished than vellum, but with no distinction between skin of calf, or sheep, or of goat. It is for these reasons that many modern conservators, librarians and archivists prefer to use either the broader term parchment, or the neutral term animal membrane. German parchmenter, 1568 The word parchment evolved from the name of the city of Pergamon, which was a thriving center of parchment production during the Hellenistic period. The city so dominated the trade that a legend later arose which said that parchment had been invented in Pergamon to replace the use of papyrus which had become monopolized by the rival city of Alexandria. This account, originating in the writings of Pliny the Elder, is false because parchment had been in use in Anatolia and elsewhere long before the rise of Pergamon. Herodotus mentions writing on skins as common in his time, the 5th century BC; and in his Histories he states that the Ionians of Asia Minor had been accustomed to give the name of skins to books; this word was adapted by Hellenized Jews to describe scrolls. In the 2nd century BC, a great library was set up in Pergamon that rivalled the famous Library of Alexandria. As prices rose for papyrus and the reed used for making it was over-harvested towards local extinction in the two nomes of the Nile delta that produced it, Pergamon adapted by increasing the use of parchment. Writing on prepared animal skins had a long history. David Diringer noted that the first mention of Egyptian documents written on leather goes back to the Fourth Dynasty, but the earliest of such documents extant are: a fragmentary roll of leather of the Sixth Dynasty, unrolled by Dr. H. Ibscher, and preserved in the Cairo Museum; a roll of the Twelfth Dynasty now in Berlin; the mathematical text now in the British Museum; and a document of the reign of Ramses II. Though the Assyrians and the Babylonians impressed their cuneiform on clay tablets, they also wrote on parchment from the 6th century BC onward. In the later Middle Ages, especially the 15th century, parchment was largely replaced by paper for most uses except luxury manuscripts, some of which were also on paper. New techniques in paper milling allowed it to be much cheaper than parchment; it was made of textile rags and of very high quality. With the advent of printing in the later fifteenth century, the demands of printers far exceeded the supply of animal skins for parchment.

more...