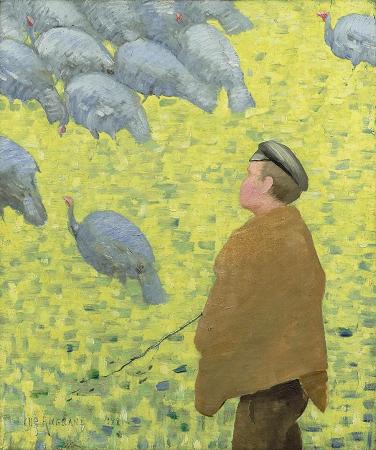

Turkey. The turkey is a large bird in the genus Meleagris, native to North America. There are two extant turkey species: the wild turkey of eastern and central North America and the ocellated turkey of the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. Males of both turkey species have a distinctive fleshy wattle, called a snood, that hangs from the top of the beak. They are among the largest birds in their ranges. As with many large ground-feeding birds, the male is bigger and much more colorful than the female. The earliest turkeys evolved in North America over 20 million years ago. They share a recent common ancestor with grouse, pheasants, and other fowl. The wild turkey species is the ancestor of the domestic turkey, which was domesticated approximately 2,000 years ago by indigenous peoples. It was this domesticated turkey that later reached Eurasia, during the Columbian exchange. In English, the name turkey probably comes from birds being brought to Britain by merchants trading to Turkey and thus becoming known as turkey coqs or turkey-cocks. This happened first to guinea fowl native to Madagascar, and then to the domesticated turkeys themselves which looked similar. This name prevailed for the turkeys, and was then transferred to the New World bird by English colonizers with knowledge of the previous species. A male ocellated turkey with a blue head The genus Meleagris was introduced in 1758 by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae. The genus name is from the Ancient Greek, meleagris meaning guineafowl. The type species is the wild turkey. Turkeys are classed in the family Phasianidae in the taxonomic order Galliformes. They are close relatives of the grouse and are classified alongside them in the tribe. The linguist Mario Pei proposes two possible explanations for the name turkey. One theory suggests that when Europeans first encountered turkeys in the Americas, they incorrectly identified the birds as a type of guineafowl, which were already being imported into Europe by English merchants to the Levant via Constantinople. The birds were therefore nicknamed turkey coqs. The name of the North American bird may have then become turkey fowl or Indian turkeys, which was eventually shortened to turkeys. A second theory arises from turkeys coming to England not directly from the Americas, but via merchant ships from the Middle East, where they were domesticated successfully. Again the importers lent the name to the bird; hence turkey-cocks and turkey-hens, and soon thereafter, turkeys. In 1550, the English navigator William Strickland, who had introduced the turkey into England, was granted a coat of arms including a turkey-cock in his pride proper. William Shakespeare used the term in Twelfth Night, believed to be written in 1601 or 1602. The lack of context around his usage suggests that the term was already widespread. Other European names for turkeys incorporate an assumed Indian origin, such as in French, in Russian, in Polish and Ukrainian, and in Turkish. These are thought to arise from the supposed belief of Christopher Columbus that he had reached India rather than the Americas on his voyage. In Portuguese a turkey is a; the name is thought to derive from Peru '. Several other birds that are sometimes called turkeys are not particularly closely related: the brushturkeys are megapodes, and the bird sometimes known as the Australian turkey is the Australian bustard. The anhinga is sometimes called the water turkey, from the shape of its tail when the feathers are fully spread for drying. An infant turkey is called a chick or poult. Depiction of ocellated turkeys in Maya codices according to the 1910 book, Animal figures in the Maya codices by Alfred Tozzer and Glover Morrill Allen Turkeys were likely first domesticated in Pre-Columbian Mexico, where they held a cultural and symbolic importance.

more...