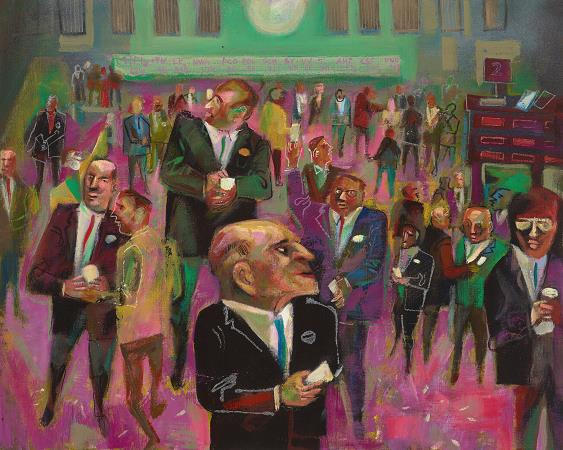

William Gropper (1897 - 1977). William Gropper was an American cartoonist, painter, lithographer, and muralist. A committed radical, Gropper is best known for the political work which he contributed to such left wing publications as The Revolutionary Age, The Liberator, The New Masses, The Worker, and Morgen Freiheit. Gropper was born to Harry and Jenny Gropper in New York City, the eldest of six children. His parents were Jewish immigrants from Romania and Ukraine, who were both employed in the city's garment industry, living in poverty on New York's Lower East Side. His mother worked hard sewing piecework at home. Harry Gropper, Bill's father, was university educated and fluent in eight languages, but was unable to find employment in America in a field for which he was suited. This failure of the American economic system to make proper use of his father's talents doubtlessly contributed to William Gropper's lifelong antipathy toward capitalism. Gropper's alienation was accentuated when on March 24, 1911, he lost a favorite aunt in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, a disaster which resulted from locked doors and non-existent exits in a New York sweatshop. Some 146 workers burned or jumped to their deaths on that day in what was New York's greatest human catastrophe prior to the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. Gropper's interest in art began at a young age. As a child of six young he took chalk to the sidewalks, decorating the concrete with elaborate picture stories of cowboys and Indians that extended around the block. As a child on the way to school, Gropper used to lug bundles of his mother's piecework sewing to the sweatshops by which she was employed. At age 13, Gropper took his first art instruction at the radical Ferrer School, where he studied under George Bellows and Robert Henri. Cartoon from the June 1920 issue of The Liberator. In 1913, Gropper graduated from public school, earning a medal in art and a scholarship to the National Academy of Design. The strong-willed Gropper refused to conform at the academy, however, and was subsequently expelled. He attempted to attend high school that fall, but finances prevented his attendance and he was forced to seek work to help support his family. He worked as an assistant in a clothing store, earning $5 a week. In 1915, Gropper showed a portfolio of his work to Frank Parsons, the head of the New York School of Fine and Applied Arts. The work so impressed Parsons that Gropper was offered a scholarship to the school. Gropper continued to work reduced hours for reduced wages in the clothing store while he continued his artistic education. In the subsequent two years, Gropper gained recognition and awards for his work. In 1917, Gropper was offered a position on the staff of the New York Tribune, where over the next several years he earned a steady income doing drawings for the paper's special Sunday feature articles. At this time, the politically radical Gropper was brought into the orbit of original and innovative artists around the left wing New York monthly, The Masses. After The Masses was banned from the U.S. Mail in 1917, due to its unflinching anti-militarism, Gropper joined artists like Robert Minor, Maurice Becker, Art Young, Lydia Gibson, Hugo Gellert, and Boardman Robinson in contributing to its successor, The Liberator. Gropper also contributed his art to The Revolutionary Age, a revolutionary socialist weekly edited by Louis C. Fraina and John Reed, a publication which narrowly predated the establishment of the American Communist Party, as well as to The Rebel Worker, a magazine of the Industrial Workers of the World, an anarcho-syndicalist union. In 1920, Gropper went to Cuba briefly as an oiler on a United Fruit Company freight boat. He left the ship in Cuba and spent some time there observing life and working as a supervisor on a railroad construction detail. He was forced to return home sooner than expected, however, owing to the terminal illness of his father. In January 1921, editor Max Eastman formally made Gropper a special contributor and member of the staff of The Liberator. His time at the publication was not harmonious however, as many of the unpaid and underpaid artists and writers greatly resented Eastman, who collected a relatively opulent paycheck of $75 a week for, as Gropper later recalled, lying on a couch and composing poetry and reading books. A little coup was short-circuited in the end by Eastman's own determination to give up his post so as to visit Soviet Russia in 1922, a decision no doubt accelerated by the magazine's growing financial woes.

more...