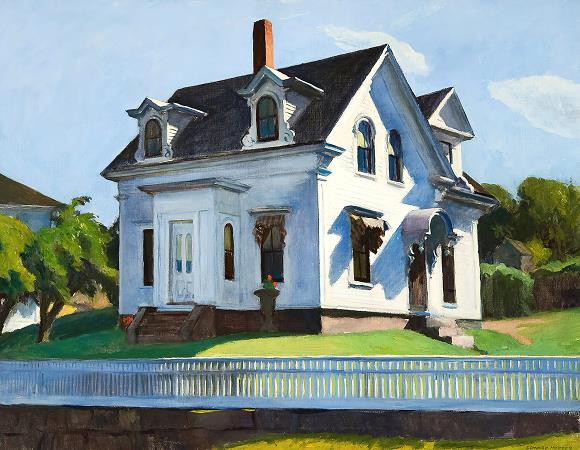

Hopper in Gloucester Art Tour. By 1923, Hopper's slow climb finally produced a breakthrough. He re-encountered Josephine Nivison, an artist and former student of Robert Henri, during a summer painting trip in Gloucester, Massachusetts. They were opposites: she was short, open, gregarious, sociable, and liberal, while he was tall, secretive, shy, quiet, introspective, and conservative. With Jo's encouragement, Hopper turned to the medium of watercolor, producing numerous scenes of Gloucester. They married a year later with artist Guy Pene du Bois as their best man. Nivison once remarked: Sometimes talking to Eddie is just like dropping a stone in a well, except that it doesn't thump when it hits bottom. She subordinated her career to his and shared his reclusive life style. The rest of their lives revolved around their spare walk-up apartment in the city and their summers in South Truro on Cape Cod. She managed his career and his interviews, was his primary model, and was his life companion. With Nivison's help, six of Hopper's Gloucester watercolors were admitted to an exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum in 1923. One of them, The Mansard Roof, was purchased by the museum for its permanent collection for the sum of $100. The critics generally raved about his work; one stated, What vitality, force and directness! Observe what can be done with the homeliest subject. Hopper sold all his watercolors at a one-man show the following year and finally decided to put illustration behind him. The artist had demonstrated his ability to transfer his attraction to Parisian architecture to American urban and rural architecture. According to Boston Museum of Fine Arts curator Carol Troyen, Hopper really liked the way these houses, with their turrets and towers and porches and mansard roofs and ornament cast wonderful shadows. Hopper always said that his favorite thing was painting sunlight on the side of a house. At forty-one, Hopper received further recognition for his work. He continued to harbor bitterness about his career, later turning down appearances and awards. With his financial stability secured by steady sales, Hopper would live a simple, stable life and continue creating art in his personal style for four more decades. His Two on the Aisle sold for a personal record $1,500, enabling Hopper to purchase an automobile, which he used to make field trips to remote areas of New England. In 1929, he produced Chop Suey and Railroad Sunset. The following year, art patron Stephen Clark donated House by the Railroad to the Museum of Modern Art, the first oil painting that it acquired for its collection. Hopper painted his last self-portrait in oil around 1930. Although Josephine posed for many of his paintings, she sat for only one formal oil portrait by her husband, Jo Painting. Hopper fared better than many other artists during the Great Depression. His stature took a sharp rise in 1931 when major museums, including the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, paid thousands of dollars for his works. He sold 30 paintings that year, including 13 watercolors. The following year he participated in the first Whitney Annual, and he continued to exhibit in every annual at the museum for the rest of his life. In 1933, the Museum of Modern Art gave Hopper his first large-scale retrospective. In 1930, the Hoppers rented a cottage in South Truro, on Cape Cod. They returned every summer for the rest of their lives, building a summer house there in 1934. From there, they would take driving trips into other areas when Hopper needed to search for fresh material to paint. In the summers of 1937 and 1938, the couple spent extended sojourns on Wagon Wheels Farm in South Royalton, Vermont, where Hopper painted a series of watercolors along the White River. These scenes are atypical among Hopper's mature works, as most are pure landscapes, devoid of architecture or human figures. First Branch of the White River, now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, is the best-known of Hopper's Vermont landscapes.

more...