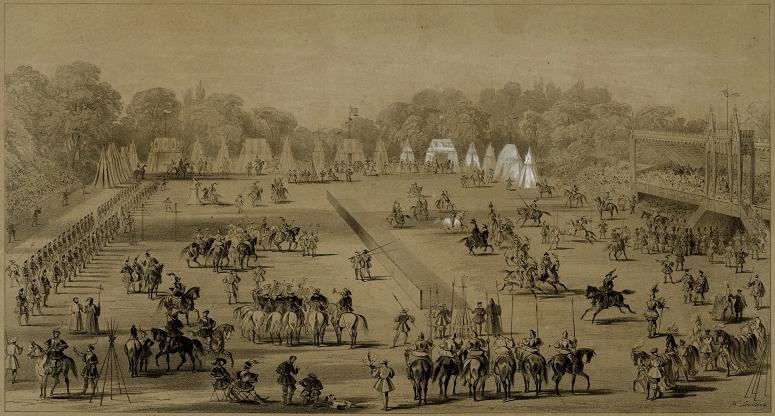

Eglinton Tournament (c1839). Lithograph. 25 x 47. After Karl Loeillot. The Eglinton Tournament of 1839 was a re-enactment of a medieval joust and revel held in Scotland between 28 and 30 August. It was funded and organized by Archibald, Earl of Eglinton, and took place at Eglinton Castle in Ayrshire. The Queen of Beauty was Georgiana, Duchess of Somerset. Many distinguished visitors took part, including Prince Louis Napoleon, the future Emperor of the French. The Tournament was a deliberate act of Romanticism, and drew 100,000 spectators. It is primarily known now for the ridicule poured on it by the Whigs. Problems were caused by rainstorms. At the time views were mixed: Whatever opinion may be formed of the success of the Tournament, as an imitation of ancient manners and customs, we heard only one feeling of admiration expressed at the gorgeousness of the whole scene, considered only as a pageant. Even on Wednesday, when the procession was seen to the greatest possible disadvantage, the dullest eye glistened with delight as the lengthy and stately train swept into the marshalled lists. Participants had undergone regular training. The preparations, and the many works of art commissioned for or inspired by the Eglinton Tournament, had an effect on public feeling and the course of 19th-century Gothic revivalism. Its ambition carried over to events such as the lavish Tournament of Brussels in 1905, and presaged the historical reenactments of the present. Features of the tournament were actually inspired by Walter Scott's novel Ivanhoe: it was attempting to be a living re-enactment of the literary romances. In Eglinton's own words I am aware of the manifold deficiencies in its exhibition, more perhaps than those who were not so deeply interested in it; I am aware that it was a very humble imitation of the scenes which my imagination had portrayed, but I have, at least, done something towards the revival of chivalry. While others made a profit, Lord Eglinton had to absorb losses. The Earl's granddaughter, Viva Montgomerie recalled in her memoirs that he had spent most of the wealth of the estate. The Gothic Revival and the rise of Romanticism of the late 18th and early 19th centuries were an international phenomenon. Medieval-style jousts, for example, were regularly held in Sweden between 1777 and 1800. Gothic novels, such as The Castle of Otranto, by Horace Walpole and the many works of Sir Walter Scott popularised the idea of passionate romanticism and praise of chivalric ideals. Walpole himself was one of the first in England to renovate his mansion into a mock-Gothic castle, Strawberry Hill. Medieval culture was widely admired as an antidote to the modern enlightenment and industrial age. Plays and theatrical works perpetuated the romanticism of knights, castles, feasts and tournaments. Caspar David Friedrich of Germany painted magnificent Gothic ruins and spiritual allegories. Jane Austen wrote her novel Northanger Abbey as a satire on romantic affectation. The Montgomerie family had a romantic tale of chivalry which bound them to the idea of a revival of such ideals, this being the acquisition of the pennon and spear of Harry Hotspur, aka Sir Henry Percy, at the Battle of Otterburn by a Montgomerie. The price for Hotspur's release was the building of the castle of Polnoon in Eaglesham, Renfrewshire for the Montgomeries. It is said that the Duke of Northumberland, head of the Percy family, made overtures for the return of the pennon in 1839 and was given the answer, There's as good lea land at Eglinton as ever there was at Chevy Chase; let Percy come and take them. In 1838 Whig Prime Minister Lord Melbourne announced that the coronation of Queen Victoria would not include the traditional medieval-style banquet in Westminster Hall. Seeking to disempower the monarchy in particular and romantic ideology and politics in general was a normal activity for the Whig party, so, in the face of recession, the more obviously anachronistic parts of the coronation celebrations would be considered an extravagance. Furthermore, memories of embarrassing mishap at George IV's Westminster Hall banquet were still fresh; uproar having resulted when, at the end of the proceedings, people tried to obtain valuable tableware as souvenirs. King William IV had cancelled his banquet to prevent a repeat. Although there was some popular support for government refusal to hold the traditional event, there were many complaints and various public struggles, as well as on the part of the antiquaries, as on that of the tradesmen of the metropolis. Critics referred to Victoria's slimmed-down coronation scornfully as The Penny Crowning. Despite attempts to achieve economies, contemporary accounts point out that Victoria's coronation in fact cost E20,000 more than that of George IV.

more...