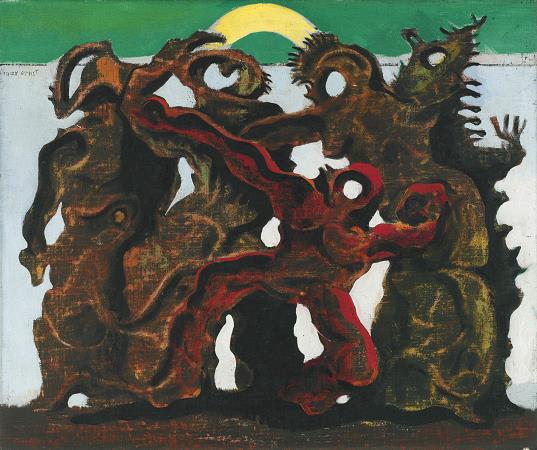

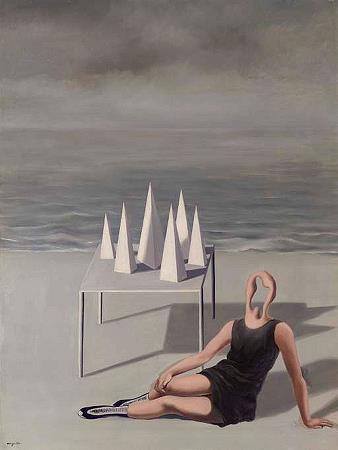

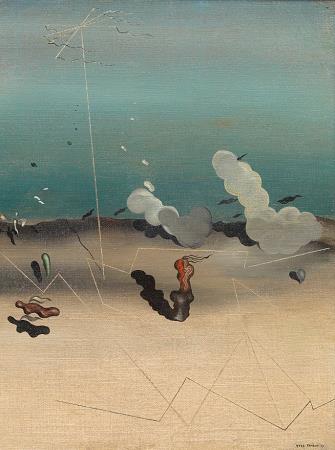

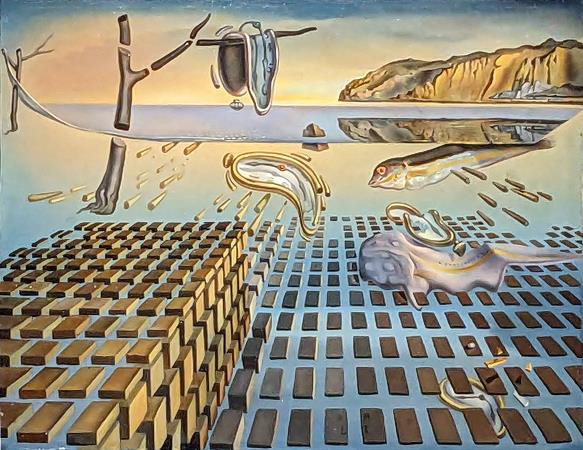

Surrealism Painting. Surrealism is a cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists depicted unnerving, illogical scenes and developed techniques to allow the unconscious mind to express itself. Its aim was, according to leader André Breton, to resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super-reality, or surreality. It produced works of painting, writing, theatre, filmmaking, photography, and other media. Works of Surrealism feature the element of surprise, unexpected juxtapositions and non sequitur. However, many Surrealist artists and writers regard their work as an expression of the philosophical movement first and foremost, with the works themselves being secondary, i.e. artifacts of surrealist experimentation. Leader Breton was explicit in his assertion that Surrealism was, above all, a revolutionary movement. At the time, the movement was associated with political causes such as communism and anarchism. It was influenced by the Dada movement of the 1910s. The term Surrealism originated with Guillaume Apollinaire in 1917. However, the Surrealist movement was not officially established until after October 1924, when the Surrealist Manifesto published by French poet and critic André Breton succeeded in claiming the term for his group over a rival faction led by Yvan Goll, who had published his own surrealist manifesto two weeks prior. The most important center of the movement was Paris, France. From the 1920s onward, the movement spread around the globe, impacting the visual arts, literature, film, and music of many countries and languages, as well as political thought and practice, philosophy, and social theory. The word surrealism was first coined in March 1917 by Guillaume Apollinaire. He wrote in a letter to Paul Dermée: All things considered, I think in fact it is better to adopt surrealism than supernaturalism, which I first used. Apollinaire used the term in his program notes for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, Parade, which premiered 18 May 1917. Parade had a one-act scenario by Jean Cocteau and was performed with music by Erik Satie. Cocteau described the ballet as realistic. Apollinaire went further, describing Parade as surrealistic: This new alliance, I say new, because until now scenery and costumes were linked only by factitious bonds, has given rise, in Parade, to a kind of surrealism, which I consider to be the point of departure for a whole series of manifestations of the New Spirit that is making itself felt today and that will certainly appeal to our best minds. We may expect it to bring about profound changes in our arts and manners through universal joyfulness, for it is only natural, after all, that they keep pace with scientific and industrial progress. The term was taken up again by Apollinaire, both as subtitle and in the preface to his play Les Mamelles de Tirésias: Drame surréaliste, which was written in 1903 and first performed in 1917. World War I scattered the writers and artists who had been based in Paris, and in the interim many became involved with Dada, believing that excessive rational thought and bourgeois values had brought the conflict of the war upon the world. The Dadaists protested with anti-art gatherings, performances, writings and art works. After the war, when they returned to Paris, the Dada activities continued. During the war, André Breton, who had trained in medicine and psychiatry, served in a neurological hospital where he used Sigmund Freud's psychoanalytic methods with soldiers suffering from shell-shock. Meeting the young writer Jacques Vaché, Breton felt that Vaché was the spiritual son of writer and pataphysics founder Alfred Jarry. He admired the young writer's anti-social attitude and disdain for established artistic tradition. Later Breton wrote, In literature, I was successively taken with Rimbaud, with Jarry, with Apollinaire, with Nouveau, with Lautréamont, but it is Jacques Vaché to whom I owe the most. Back in Paris, Breton joined in Dada activities and started the literary journal Littérature along with Louis Aragon and Philippe Soupault. They began experimenting with automatic writing, spontaneously writing without censoring their thoughts, and published the writings, as well as accounts of dreams, in the magazine. Breton and Soupault continued writing evolving their techniques of automatism and published The Magnetic Fields. By October 1924 two rival Surrealist groups had formed to publish a Surrealist Manifesto. Each claimed to be successors of a revolution launched by Appolinaire.

more...