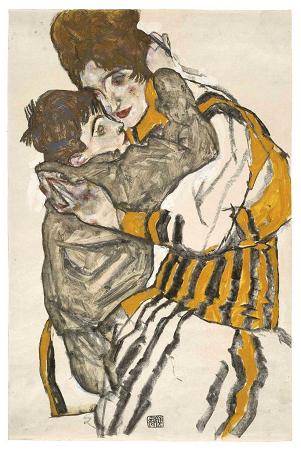

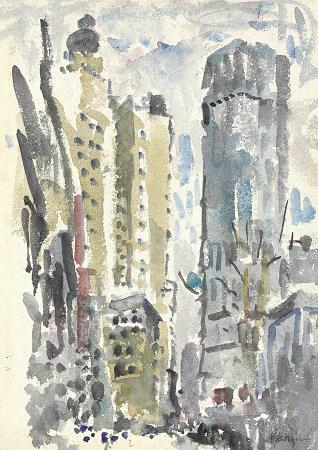

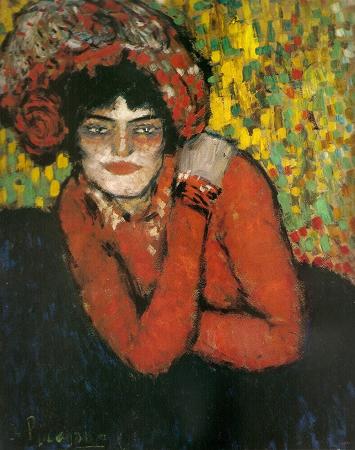

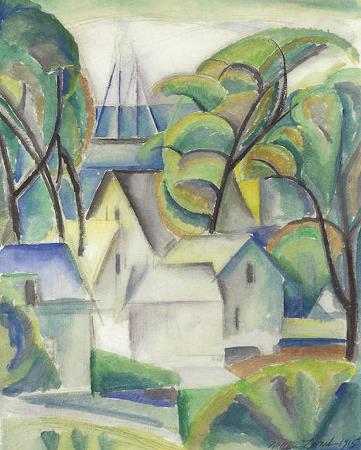

Modernism Artist. Modernism is both a philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, and social organization which reflected the newly emerging industrial world, including features such as urbanization, new technologies, and war. Artists attempted to depart from traditional forms of art, which they considered outdated or obsolete. The poet Ezra Pound's 1934 injunction to Make it New was the touchstone of the movement's approach. Modernist innovations included abstract art, the stream-of-consciousness novel, montage cinema, atonal and twelve-tone music, and divisionist painting. Modernism explicitly rejected the ideology of realism and made use of the works of the past by the employment of reprise, incorporation, rewriting, recapitulation, revision and parody. Modernism also rejected the certainty of Enlightenment thinking, and many modernists also rejected religious belief. A notable characteristic of modernism is self-consciousness concerning artistic and social traditions, which often led to experimentation with form, along with the use of techniques that drew attention to the processes and materials used in creating works of art. While some scholars see modernism continuing into the 21st century, others see it evolving into late modernism or high modernism. Postmodernism is a departure from modernism and rejects its basic assumptions. Some commentators define modernism as a mode of thinking, one or more philosophically defined characteristics, like self-consciousness or self-reference, that run across all the novelties in the arts and the disciplines. More common, especially in the West, are those who see it as a socially progressive trend of thought that affirms the power of human beings to create, improve, and reshape their environment with the aid of practical experimentation, scientific knowledge, or technology. From this perspective, modernism encouraged the re-examination of every aspect of existence, from commerce to philosophy, with the goal of finding that which was 'holding back' progress, and replacing it with new ways of reaching the same end. According to Roger Griffin, modernism can be defined as a broad cultural, social, or political initiative, sustained by the ethos of the temporality of the new. Modernism sought to restore, Griffin writes, a sense of sublime order and purpose to the contemporary world, thereby counteracting the erosion of an overarching nomos ', or sacred canopy', under the fragmenting and secularizing impact of modernity. Therefore, phenomena apparently unrelated to each other such as Expressionism, Futurism, vitalism, Theosophy, psychoanalysis, nudism, eugenics, utopian town planning and architecture, modern dance, Bolshevism, organic nationalism-and even the cult of self-sacrifice that sustained the hecatomb of the First World War-disclose a common cause and psychological matrix in the fight against decadence. All of them embody bids to access asupra-personal experience of reality, in which individuals believed they could transcend their own mortality, and eventually that they had ceased to be victims of history to become instead its creators. According to one critic, modernism developed out of Romanticism's revolt against the effects of the Industrial Revolution and bourgeois values: The ground motive of modernism, Graff asserts, was criticism of the nineteenth-century bourgeois social order and its world view the modernists, carrying the torch of romanticism. While J. M. W. Turner, one of the greatest landscape painters of the 19th century, was a member of the Romantic movement, as a pioneer in the study of light, colour, and atmosphere, he anticipated the French Impressionists and therefore modernismin breaking down conventional formulas of representation; unlike them, he believed that his works should always express significant historical, mythological, literary, or other narrative themes. The dominant trends of industrial Victorian England were opposed, from about 1850, by the English poets and painters that constituted the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, because of their opposition to technical skill without inspiration. They were influenced by the writings of the art critic John Ruskin, who had strong feelings about the role of art in helping to improve the lives of the urban working classes, in the rapidly expanding industrial cities of Britain.

more...