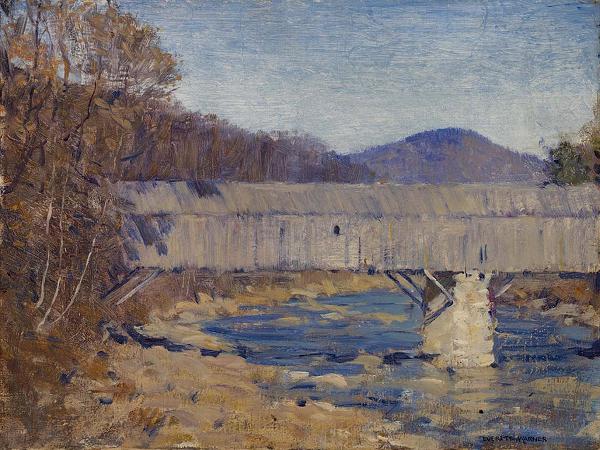

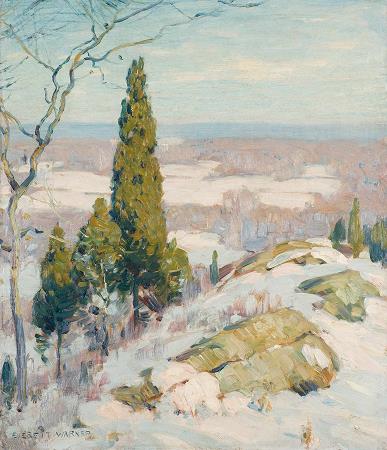

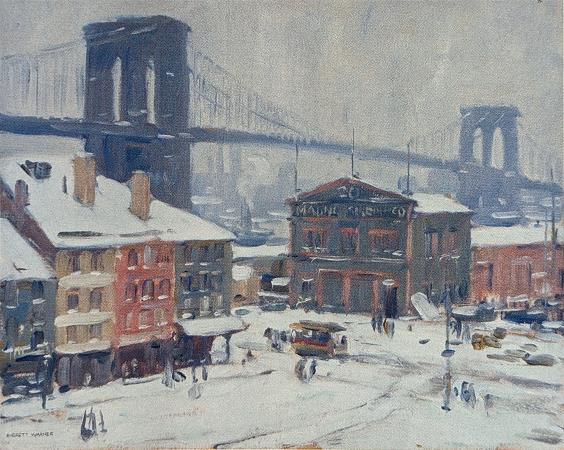

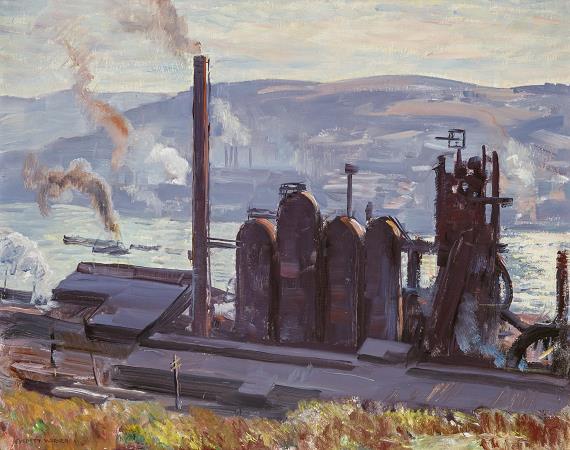

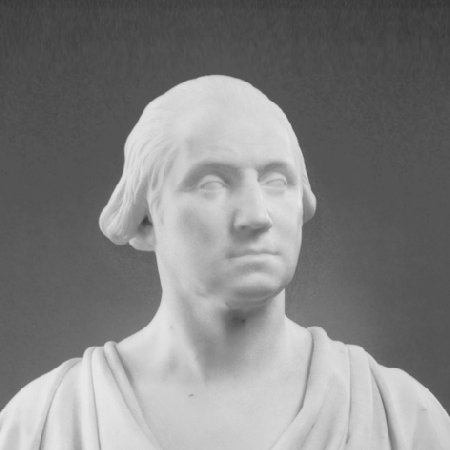

Everett Warner (1877 - 1963). Everett Longley Warner was an American Impressionist painter and printmaker, as well as a leading contributor to US Navy camouflage during both World Wars. Warner was born in the small town of Vinton, Iowa, where his father was a lawyer. His mother was descended from a line of prominent missionaries, who worked extensively for years with the Dakota Sioux Indians, translating and preserving their traditional language. Warner spent part of his childhood in Iowa, then moved to Washington, D.C., when his father was appointed Examiner for the Bureau of Pensions. While completing high school, he also went to classes at the Corcoran Museum and the Washington Art Students League. Following that, he was employed for several years as an art critic for the Evening Star. In 1900, he moved to New York and studied at the Art Students League with life drawing master George Bridgman and illustrator Walter Clark. His work was soon selected for inclusion in some of the country's most prestigious art competitions, at the Art Institute of Chicago, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the National Academy of Design, In 1903, with earnings from his painting sales, Warner traveled to Europe, where he studied in Paris at the Académie Julian, while also making sketching trips to Italy, Germany, Spain, the Netherlands, and other countries. Returning permanently to the US in 1909, he became affiliated with the Old Lyme Art Colony at Old Lyme, Connecticut, which had become a well-known center for American Impressionism. One of the leading participants in that colony was Childe Hassam, who was a close associate of Abbott H. Thayer, a painter who was widely known for his theories of natural camouflage. In 1915, at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, Warner won a silver medal in the painting category, and a bronze medal in printmaking. Featured prominently at that World's Fair were the allegorical sculptures of Iowa-born artist Sherry Edmundson Fry, who was awarded a silver medal, and who, a few years later, teamed up with New Hampshire painter Barry Faulkner to establish an artists' camouflage corps. Ironically, at around this time, an inevitable decline began in the career prospects of all these young artists, many of whom were very gifted, largely because of the interest in Modern Art, which had been loudly introduced to the American public in 1913 at the famous New York Armory Show. As noted by Helen K. Fusscas in A World Observed: The Art of Everett Longley Warner, By introducing European modernism to this country, the Armory Show made American Impressionism seem decidedly old-fashioned and uninteresting. In the years that followed, Warner and the others continued to work as artists, to exhibit, and to win awards, but they never achieved the stature that they might once have anticipated. When the US entered World War I in 1917, Warner searched for ways to contribute to the war effort. He considered a range of options, and even applied for the American Camouflage Corps. For many years, one of his closest friends had been the MIT-trained scientist and Paris-trained artist Charles Bittinger, who would later play a prominent role in World War II ship camouflage. It may have been through Bittinger that Warner was approached by the US Shipping Board to carry out a camouflage scheme invented by Thomas A. Edison. Using Edison's specifications, Warner applied that scheme to a former German ocean liner, the SS Ockenfels. Although the result was intended to be an invisible ship, it was not only readily visible but was structurally absurd as well, with the result that a section attached to the bow had fallen off before the ship left New York harbor. Recalling that fiasco, Warner said, Thereafter I was for distortion patterns which make a ship hard to hit, not hard to see. A few months later, Warner presented his own ship camouflage plan to the US government. According to existing records, he argued that it is impossible to make a ship invisible from a submarine, because she was almost invariably outlined against the sky and consequently would show up in silhouette. His proposal, therefore, was to break up the silhouette in such as way as to make it very difficult for the enemy to obtain the range. This method, known officially as the Warner System, was one of six camouflage measures approved by the US, with others having been devised by George de Forest Brush, William Mackay, Lewis Herzog, Maximilian Toch, and a person named Watson. In February 1918, Warner accepted a commission as a lieutenant in the US Naval Reserves, and was assigned to manage a design-based subdivision of a newly formed American Camouflage Section.

more...