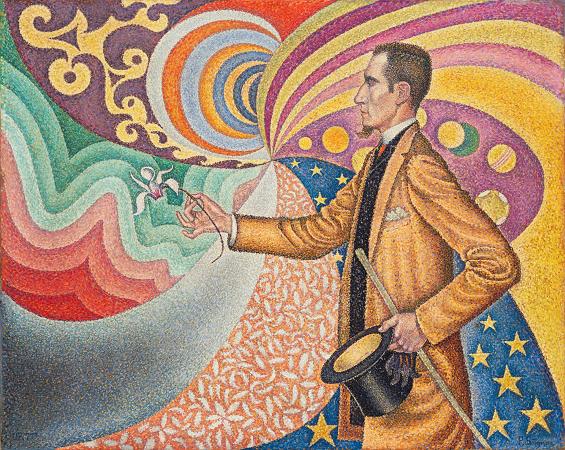

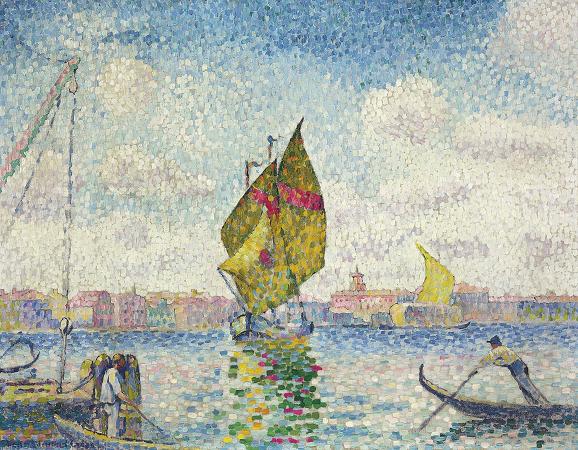

Neo-Impressionism Painting. Neo-Impressionism is a term coined by French art critic Félix Fénéon in 1886 to describe an art movement founded by Georges Seurat. Seurat's most renowned masterpiece, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, marked the beginning of this movement when it first made its appearance at an exhibition of the Société des Artistes Indépendants in Paris. Around this time, the peak of France's modern era emerged and many painters were in search of new methods. Followers of Neo-Impressionism, in particular, were drawn to modern urban scenes as well as landscapes and seashores. Science-based interpretation of lines and colors influenced Neo-Impressionists' characterization of their own contemporary art. The Pointillist and Divisionist techniques are often mentioned in this context, because it was the dominant technique in the beginning of the Neo-impressionist movement. Some argue that Neo-Impressionism became the first true avant-garde movement in painting. The Neo-Impressionists were able to create a movement very quickly in the 19th century, partially due to its strong connection to anarchism, which set a pace for later artistic manifestations. The movement and the style were an attempt to drive harmonious vision from modern science, anarchist theory, and late 19th-century debate around the value of academic art. The artists of the movement promised to employ optical and psycho-biological theories in pursuit of a grand synthesis of the ideal and the real, the fugitive and the essential, science and temperament. During the emergence of Neo-Impressionism, Seurat and his followers strove to refine the impulsive and intuitive artistic mannerisms of Impressionism. Neo-impressionists used disciplined networks of dots and blocks of color in their desire to instill a sense of organization and permanence. In further defining the movement, Seurat incorporated the recent explanation of optic and color perceptions. The development of color theory by Michel Eugène Chevreul and others by the late 19th century played a pivotal role in shaping the Neo-Impressionist style. Ogden Rood's book, Modern Chromatics, with Applications to Art and Industry, acknowledged the different behaviors exhibited by colored light and colored pigment. While the mixture of the former created a white or gray color, that of the latter produced a dark, murky color. As painters, Neo-Impressionists had to deal with colored pigments, so to avoid the dullness, they devised a system of pure-color juxtaposition. Mixing of colors was not necessary. The effective utilization of pointillism facilitated in eliciting a distinct luminous effect, and from a distance, the dots came together as a whole displaying maximum brilliance and conformity to actual light conditions. There are a number of alternatives to the term Neo-Impressionism and each has its own nuance: Chromoluminarism was a term preferred by Georges Seurat. It emphasized the studies of color and light which were central to his artistic style. This term is rarely used today. Divisionism, which is more commonly used, is used to describe a mode of Neo-Impressionist painting. It refers to the method of applying individual strokes of complementary and contrasting colors. Unlike other designations of this era, the term Neo-Impressionism was not given as a criticism. Instead, it embraces Seurat's and his followers' ideals in their approach to art.Note: Pointillism merely describes a later technique based on divisionism in which dots of color instead of blocks of color are applied. Neo-Impressionism was first presented to the public in 1886 at the Salon des Indépendants. The Indépendants remained their main exhibition space for decades with Signac acting as president of the association. But with the success of Neo-Impressionism, its fame spread quickly. In 1886, Seurat and Signac were invited to exhibit in the 8th and final Impressionist exhibition, later with Les XX and La Libre Esthétique in Brussels. In 1892, a group of Neo-Impressionist painters united to show their works in Paris, in the Salons of the Hôtel Brébant, 32, boulevard Poissonnière. The following year they exhibited at 20, rue Laffitte. The exhibitions were accompanied by catalogues, the first with reference to the printer: Imp. Vve Monnom, Brussels; the second refers to M. Moline, secretary. Pissarro and Seurat met at Durand-Ruel's in the fall of 1885 and began to experiment with a technique using tiny dots of juxtaposing colors. This technique was developed from readings of popular art history and aesthetics, and manuals for the industrial and decorative arts, science of optics and perception.

more...