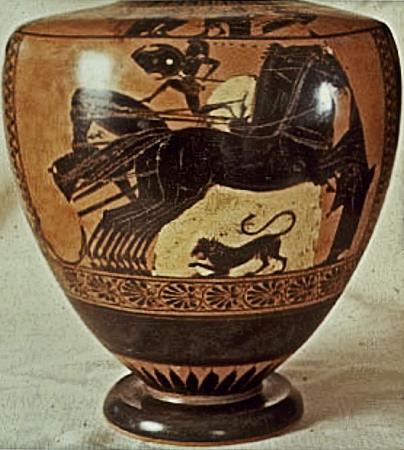

Chariot Race. Chariot racing was one of the most popular Iranian, ancient Greek, Roman, and Byzantine sports. Chariot racing was dangerous to both drivers and horses as they often suffered serious injury and even death, but these dangers added to the excitement and interest for spectators. Chariot races could be watched by women, who were banned from watching many other sports. In the Roman form of chariot racing, teams represented different groups of financial backers and sometimes competed for the services of particularly skilled drivers. As in modern sports like football, spectators generally chose to support a single team, identifying themselves strongly with its fortunes, and violence sometimes broke out between rival factions. The rivalries were sometimes politicized, when teams became associated with competing social or religious ideas. This helps explain why Roman and later Byzantine emperors took control of the teams and appointed many officials to oversee them. The sport faded in importance in the West after the fall of Rome. It survived much longer in the Byzantine Empire, where the traditional Roman factions continued to play a prominent role for several centuries, gaining influence in political matters. Their rivalry culminated in the Nika riots, which marked the gradual decline of the sport. It is unknown exactly when chariot racing began, but it may have been as old as the chariots themselves. It is known from artistic evidence on pottery that the sport existed in the Mycenaean world, but the first literary reference to a chariot race is one described in the Iliad by Homer, at the funeral games of Patroclus. The participants in this race were Diomedes, Eumelus, Antilochus, Menelaus, and Meriones. The race, which was one lap around the stump of a tree, was won by Diomedes, who received a slave woman and a cauldron as his prize. A chariot race also was said to be the event that founded the Olympic Games; according to one legend, mentioned by toilet, King Oenomaus challenged suitors for his daughter Hippodamia to a race, but was defeated by Pelops, who founded the Games in honour of his victory. In the ancient Olympic Games, as well as the other Panhellenic Games, there were both four-horse and two-horse chariot races, which were essentially the same aside from the number of horses. The chariot racing event was first added to the Olympics in 680 BC with the games expanding from a one-day to a two-day event to accommodate the new event. The chariot race was not so prestigious as the foot race of 195 meters, but it was more important than other equestrian events such as racing on horseback, which were dropped from the Olympic Games very early on. The races themselves were held in the hippodrome, which held both chariot races and riding races. The single horse race was known as the keles. The hippodrome was situated at the south-east corner of the sanctuary of Olympia, on the large flat area south of the stadium and ran almost parallel to the latter. Until recently, its exact location was unknown, since it is buried by several meters of sedimentary material from the Alfeios River. In 2008, however, Annie Muller and staff of the German Archeological Institute used radar to locate a large, rectangular structure similar to Pausanias's description. Pausanias, who visited Olympia in the second century AD, describes the monument as a large, elongated, flat space, approximately 780 meters long and 320 meters wide. The elongated racecourse was divided longitudinally into two tracks by a stone or wooden barrier, the embolon. All the horses or chariots ran on one track toward the east, then turned around the embolon and headed back west. Distances varied according to the event. The racecourse was surrounded by natural and artificial banks for the spectators; a special place was reserved for the judges on the west side of the north bank. The race was begun by a procession into the hippodrome, while a herald announced the names of the drivers and owners. The tethrippon consisted of twelve laps around the hippodrome, with sharp turns around the posts at either end. Various mechanical devices were used, including the starting gates which were lowered to start the race. According to Pausanias, these were invented by the architect Cleoitas, and staggered so that the chariots on the outside began the race earlier than those on the inside. The race did not begin properly until the final gate was opened, at which point each chariot would be more or less lined up alongside each other, although the ones that had started on the outside would have been traveling faster than the ones in the middle.

more...