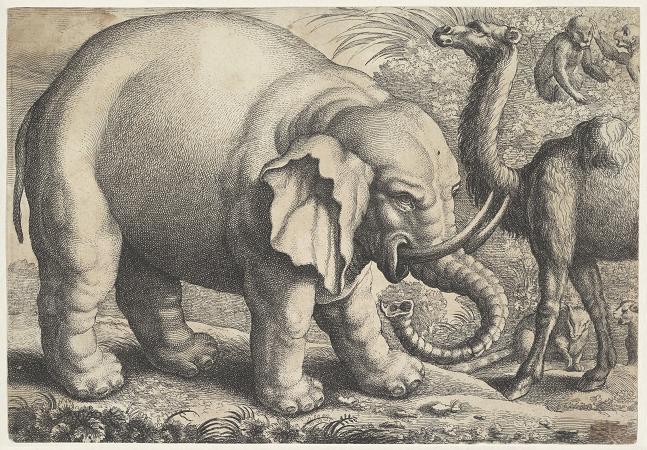

Camel. A camel is an even-toed ungulate in the genus Camelus that bears distinctive fatty deposits known as humps on its back. Camels have long been domesticated and, as livestock, they provide food and textiles. Camels are working animals especially suited to their desert habitat and are a vital means of transport for passengers and cargo. There are three surviving species of camel. The one-humped dromedary makes up 94% of the world's camel population, and the two-humped Bactrian camel makes up 6%. The Wild Bactrian camel is a separate species and is now critically endangered. The word camel is also used informally in a wider sense, where the more correct term is camelid, to include all seven species of the family Camelidae: the true camels, along with the New World camelids: the llama, the alpaca, the guanaco, and the vicuña. 3 species are extant: Image Common name Scientific name Distribution Dromedary / Arabian camel Camelus dromedarius Middle East, the Horn of Africa and South Asia Bactrian camel Camelus bactrianus Central Asia, including the historical region of Bactria. Wild Bactrian camel Camelus ferus Remote areas of northwest China and Mongolia An extinct species of camel in the separate genus Camelops, known as C. hesternus, lived in western North America until the end of the Pleistocene, roughly 11,000 years ago. The average life expectancy of a camel is 40 to 50 years. A full-grown adult dromedary camel stands 1.85 m at the shoulder and 2.15 m at the hump. Bactrian camels can be a foot taller. Camels can run at up to 65 km/h in short bursts and sustain speeds of up to 40 km/h. Bactrian camels weigh 300 to 1,000 kg and dromedaries 300 to 600 kg. The widening toes on a camel's hoof provide supplemental grip for varying soil sediments. The male dromedary camel has an organ called a dulla in its throat, a large, inflatable sac he extrudes from his mouth when in rut to assert dominance and attract females. It resembles a long, swollen, pink tongue hanging out of the side of its mouth. Camels mate by having both male and female sitting on the ground, with the male mounting from behind. The male usually ejaculates three or four times within a single mating session. Camelids are the only ungulates to mate in a sitting position. Camels do not directly store water in their humps; they are reservoirs of fatty tissue. Concentrating body fat in their humps minimizes the insulating effect fat would have if distributed over the rest of their bodies, helping camels survive in hot climates. When this tissue is metabolized, it yields more than one gram of water for every gram of fat processed. This fat metabolization, while releasing energy, causes water to evaporate from the lungs during respiration: overall, there is a net decrease in water. Camels have a series of physiological adaptations that allow them to withstand long periods of time without any external source of water. The dromedary camel can drink as seldom as once every 10 days even under very hot conditions, and can lose up to 30% of its body mass due to dehydration. Unlike other mammals, camels' red blood cells are oval rather than circular in shape. This facilitates the flow of red blood cells during dehydration and makes them better at withstanding high osmotic variation without rupturing when drinking large amounts of water: a 600 kg camel can drink 200 L of water in three minutes. Camels are able to withstand changes in body temperature and water consumption that would kill most other mammals. Their temperature ranges from 34 °C at dawn and steadily increases to 40 °C by sunset, before they cool off at night again. In general, to compare between camels and the other livestock, camels lose only 1.3 liters of fluid intake every day while the other livestock lose 20 to 40 liters per day. Maintaining the brain temperature within certain limits is critical for animals; to assist this, camels have a rete mirabile, a complex of arteries and veins lying very close to each other which utilizes countercurrent blood flow to cool blood flowing to the brain. Camels rarely sweat, even when ambient temperatures reach 49 C. Any sweat that does occur evaporates at the skin level rather than at the surface of their coat; the heat of vaporization therefore comes from body heat rather than ambient heat.

more...