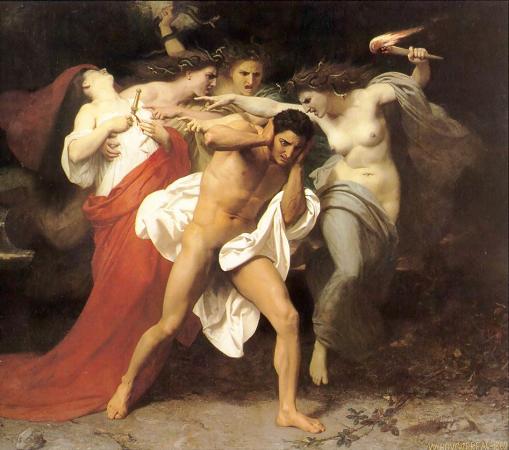

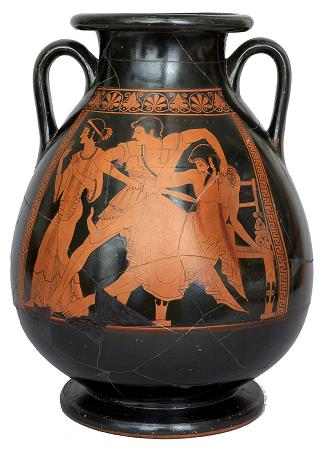

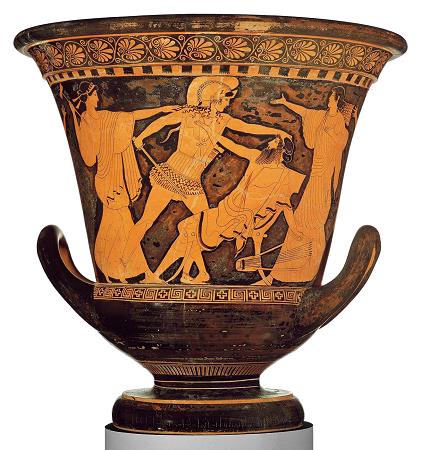

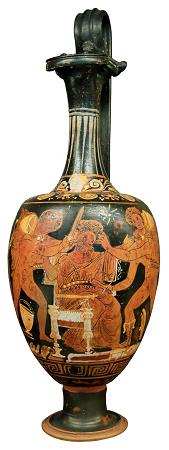

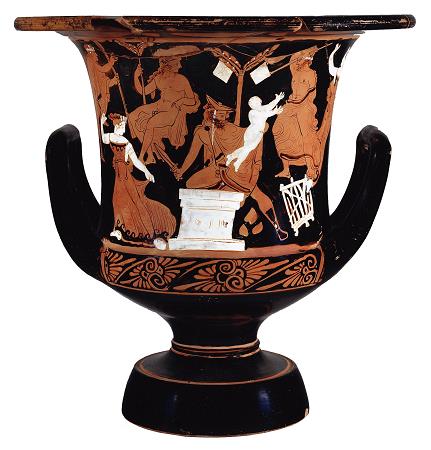

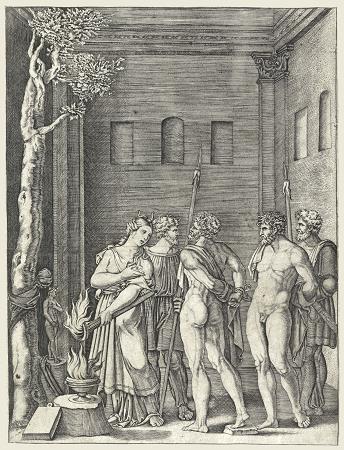

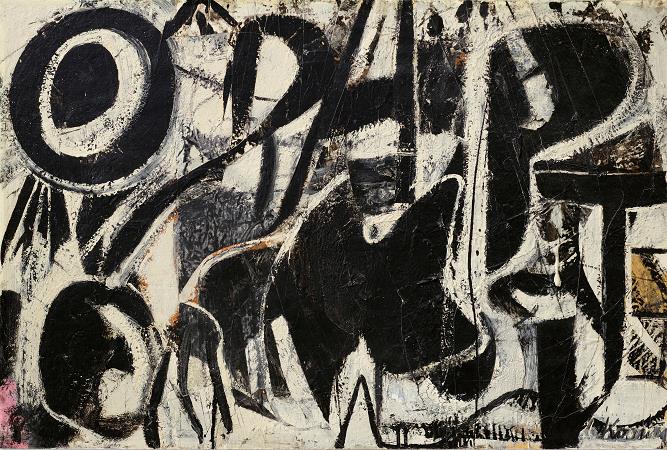

Orestes. In Greek mythology, Orestes was the son of Clytemnestra and Agamemnon. He is the subject of several Ancient Greek plays and of various myths connected with his madness and purification, which retain obscure threads of much older ones. In the Homeric telling of the story, Orestes is a member of the doomed house of Atreus which is descended from Tantalus and Niobe. Orestes is absent from Mycenae when his father, Agamemnon, returns from the Trojan War with the Trojan princess Cassandra as his concubine, and thus not present for Agamemnon's murder by his wife Clytemnestra's lover, Aegisthus. Seven years later, Orestes returns from Athens and avenges his father's death by slaying both Aegisthus and his own mother Clytemnestra. In the Odyssey, Orestes is held up as a favorable example to Telemachus, whose mother Penelope is plagued by suitors. According to Pindar, the young Orestes was saved by his nurse Arsinoe or his sister Electra, who conveyed him out of the country when Clytemnestra wished to kill him. In the familiar theme of the hero's early eclipse and exile, he escaped to Phanote on Mount Parnassus, where King Strophius took charge of him. In his twentieth year, he was urged by Electra to return home and avenge his father's death. He returned home along with his friend Pylades, Strophius's son. The same myth is told differently by Sophocles and Euripides in their Electra plays. In The Greek Myths the mythographer and poet Robert Graves translates and interprets the legends and myth fragments about Clytemnestra, Agamemnon, and Orestes, as suggesting a ritual killing of a king in very early religious ceremonies that were suppressed when patriarchy replaced the matriarchies of very ancient Greece. Graves interprets the sacrilege for which the Erinyes pursued Orestes, namely the killing of his mother, as representing symbolically the destruction of the ancient matriarchy and its replacement by patriarchy. He suggests that worship of the female deity Athena was retained as a cult because, despite the overthrow of matriarchy and woman-rule generally, it was too strong to be suppressed; Graves thinks she was recast as a child of Zeus in the new patriarchal myths. As a character in Aeschylus' trilogy, Athena was given the previously incomprehensible role of justifying the overthrow, rationalizing as a new way of justice what would have been a horrific crime against the old, matriarchal religious customs. Graves, and many other mythographers including most notably those of the Cambridge Ritualist school, were influenced by The Golden Bough of James Frazer, who postulated that myths often reveal clues to ancient religious practices and rituals. The story of Orestes was the subject of the Oresteia of Aeschylus, of the Electra of Sophocles, and of the Electra, Iphigeneia in Tauris, Iphigenia at Aulis and Orestes, all of Euripides. In Aeschylus's Eumenides, Orestes goes mad after the deed and is pursued by the Erinyes, whose duty it is to punish any violation of the ties of family piety. He takes refuge in the temple at Delphi; but, even though Apollo had ordered him to do the deed, he is powerless to protect Orestes from the consequences. At last Athena receives him on the acropolis of Athens and arranges a formal trial of the case before twelve judges, including herself. The Erinyes demand their victim; he pleads the orders of Apollo. Athena votes last announcing that she is for acquittal; then the votes are counted and the result is a tie, resulting in an acquittal according to the rules previously stipulated by Athena. The Erinyes are propitiated by a new ritual, in which they are worshipped as Semnai Theai, Venerable Goddesses, and Orestes dedicates an altar to Athena Areia. As Aeschylus tells it, the punishment ended there, but according to Euripides, in order to escape the persecutions of the Erinyes, Orestes was ordered by Apollo to go to Tauris, carry off the statue of Artemis which had fallen from heaven, and to bring it to Athens. He went to Tauris with Pylades, and the pair were at once imprisoned by the people, among whom the custom was to sacrifice all Greek strangers to Artemis. The priestess of Artemis, whose duty it was to perform the sacrifice, was Orestes' sister Iphigenia. She offered to release him if he would carry home a letter from her to Greece; he refused to go, but bids Pylades to take the letter while he stays to be slain.

more...