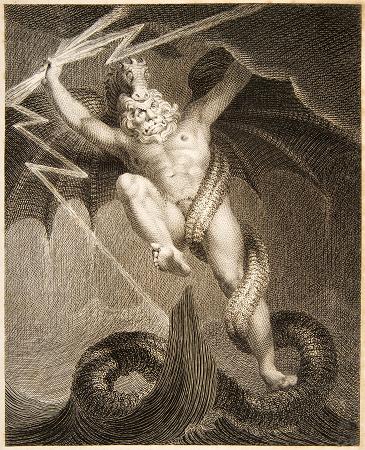

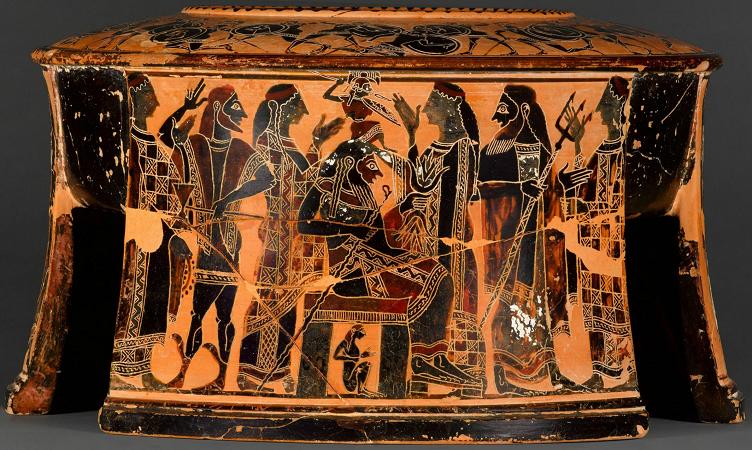

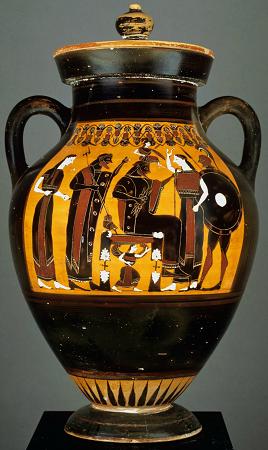

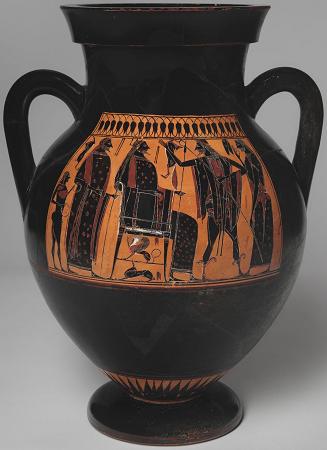

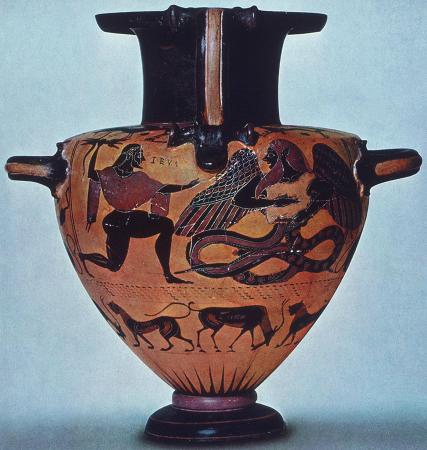

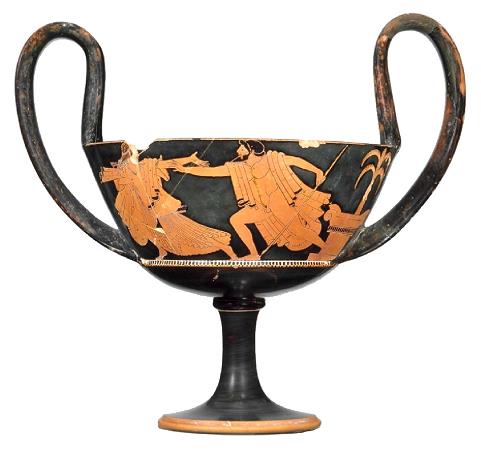

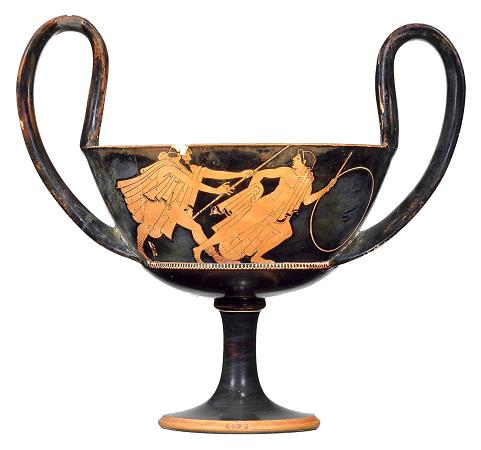

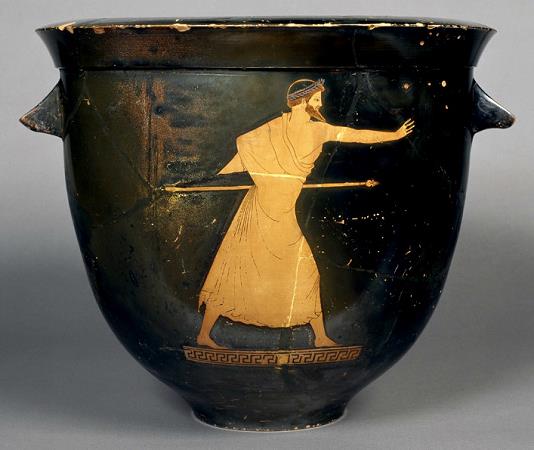

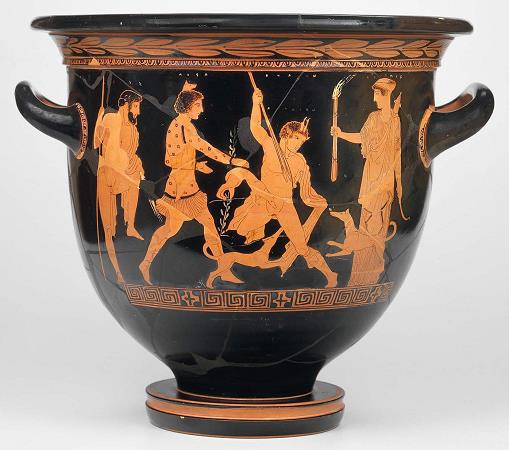

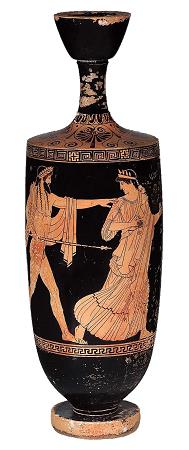

Jupiter / Zeus. Jupiter, also known as Jove, is the god of the sky and thunder and king of the gods in Ancient Roman religion and mythology. In art, he is typically shown with attributes that symbolize his authority, such as a thunderbolt, scepter, or eagle. One of Jupiter's most distinctive attributes is the thunderbolt, which symbolizes his power over the weather and his ability to hurl lightning bolts at his enemies. He may be shown holding a thunderbolt in his hand, or with one resting at his feet. The eagle is another common attribute of Jupiter, representing his sovereignty and his association with the sky. He may be shown with an eagle perched on his arm or sitting nearby. Jupiter is often depicted as a powerful and majestic figure, with a muscular physique and an air of authority. He may be shown seated on a throne or standing with a commanding presence, surrounded by symbols of his power and dominion. He is often depicted as a mature, bearded man, reflecting his status as the father of the gods and the ruler of the universe. He may be shown with a regal bearing and a stern expression, emphasizing his authority and wisdom. He may depicted in scenes from Roman mythology, such as the abduction of Europa, the rape of Ganymede, or the punishment of Prometheus. These scenes may show Jupiter in action, using his powers to achieve his goals or assert his dominance. Jupiter may also be depicted in allegorical scenes, representing concepts such as justice, wisdom, or power. For example, he may be shown holding a set of scales, representing his role as a judge, or surrounded by symbols of knowledge and learning. Some famous works of art featuring Jupiter include the Jupiter and Io by Antonio da Correggio, the Rape of Ganymede by Rembrandt, and the Jupiter and Thetis by Peter Paul Rubens. Jupiter's Greek equivalent is Zeus, and he is often depicted in a similar manner in Greek art. He was the chief deity of Roman state religion throughout the Republican and Imperial eras, until Christianity became the dominant religion of the Empire. In Roman mythology, he negotiates with Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome, to establish principles of Roman religion such as offering, or sacrifice. Jupiter is usually thought to have originated as an aerial god. His identifying implement is the thunderbolt and his primary sacred animal is the eagle, which held precedence over other birds in the taking of auspices and became one of the most common symbols of the Roman army. The two emblems were often combined to represent the god in the form of an eagle holding in its claws a thunderbolt, frequently seen on Greek and Roman coins. As the sky-god, he was a divine witness to oaths, the sacred trust on which justice and good government depend. Many of his functions were focused on the Capitoline Hill, where the citadel was located. In the Capitoline Triad, he was the central guardian of the state with Juno and Minerva. His sacred tree was the oak. The Romans regarded Jupiter as the equivalent of the Greek Zeus, and in Latin literature and Roman art, the myths and iconography of Zeus are adapted under the name Iuppiter. In the Greek-influenced tradition, Jupiter was the brother of Neptune and Pluto, the Roman equivalents of Poseidon and Hades respectively. Each presided over one of the three realms of the universe: sky, the waters, and the underworld. The Italic Diespiter was also a sky god who manifested himself in the daylight, usually identified with Jupiter. Tinia is usually regarded as his Etruscan counterpart. The Romans believed that Jupiter granted them supremacy because they had honoured him more than any other people had. Jupiter was the fount of the auspices upon which the relationship of the city with the gods rested. He personified the divine authority of Rome's highest offices, internal organization, and external relations. His image in the Republican and Imperial Capitol bore regalia associated with Rome's ancient kings and the highest consular and Imperial honours. Bas-relief of Roman driver in four-horse chariot, facing left. The consuls swore their oath of office in Jupiter's name, and honoured him on the annual feriae of the Capitol in September. To thank him for his help, they offered him a white ox with gilded horns.

more...