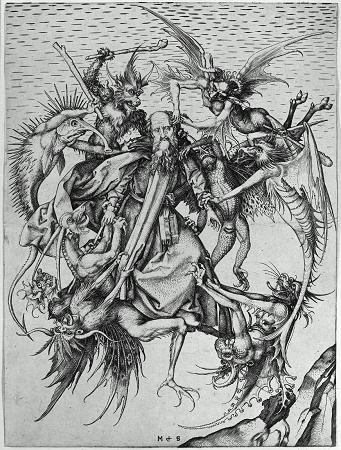

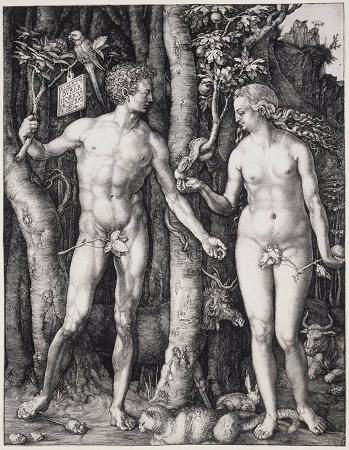

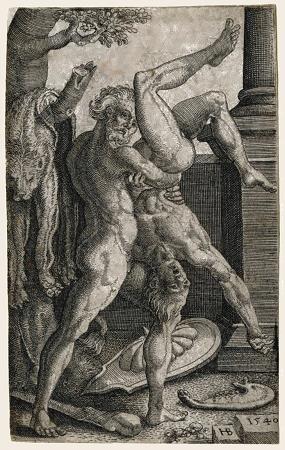

Germany Artist. German art has had a diverse range of influences. In the 10th to the 12th centuries, German Romanesque art emphasized religious themes, often in murals on church walls. In the 13th through the 15th centuries, the Gothic style with vibrant colors was dominant in church architecture and stained glass windows. In the 15th and 16th centuries, the German Renaissance explored religious themes with emotional intensity. In the 16th century, the Mannerist style explored elongated figures and dramatic lighting effects. By the 17th century, German Baroque paintings aimed to evoke religious awe. In the 18th century, the more playful Rococo style incorporated lighter themes, delicate details, and an emphasis on nature and leisure. A reaction to the emphasis on reason occured in the 19th century. Romanticism celebrated emotions, imagination, and the natural world. Realism emerged, focusing on depicting everyday life. The 20th century saw a vast array of styles in German art. Expressionism, with its distorted forms and intense emotions, flourished through artists Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. The Bauhaus movement, with its focus on functionality and clean lines, had a major impact on design and architecture. Dada and Surrealism also found expression in Germany. After World War II, German art explored themes of memory, identity, and the political division of the country. Neo-Expressionism, with its raw emotions and bold brushstrokes, became prominent. Today, German art continues to be diverse, with artists engaging in a global dialogue and exploring new forms of expression. One of the earliest and most significant influences on German art was the Roman Empire, which brought new artistic techniques and styles to the region. Following the fall of the Roman Empire, German art was heavily influenced by Celtic and Christian traditions, as well as by the artistic movements of neighboring countries such as Italy and the Netherlands. In the 15th and 16th centuries, German art entered its Renaissance period, characterized by its focus on humanism, naturalism, and the revival of classical ideals. Artists such as Albrecht Dürer and Lucas Cranach the Elder produced works that reflected the growing interest in individualism, the natural world, and the human experience. In the 18th and 19th centuries, German art was influenced by the social and political upheavals of the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution. Artists such as Caspar David Friedrich and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe produced works that reflected the changing nature of German society and the influence of international artistic movements. Friedrich's landscapes, in particular, had a profound impact on the development of Romanticism, inspiring artists from across Europe and beyond with their moody and atmospheric depictions of the natural world. In the 20th century, German art continued to evolve and diversify, reflecting the country's rich cultural heritage and its engagement with global artistic trends. Artists such as Max Ernst and Joseph Beuys produced works that challenged traditional notions of art and provoked controversy with their innovative use of materials and themes. The German Expressionist movement, led by artists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Wassily Kandinsky, also had a significant impact on the development of modern art, inspiring artists around the world with its bold use of color and form. German art has had a profound influence on the art of other regions around the world. The German Renaissance, in particular, had a significant impact on the development of Western art, inspiring artists from across Europe with its innovative techniques and themes. German artists such as Dürer and Friedrich continue to be celebrated as some of the greatest painters in the history of Western art, and their works have influenced countless artists and art movements over the centuries. Germany has only been united into a single state since the 19th century, and defining its borders has been a notoriously difficult and painful process. For earlier periods German art often effectively includes that produced in German-speaking regions including Austria, Alsace and much of Switzerland, as well as largely German-speaking cities or regions to the east of the modern German borders. The area of modern Germany is rich in finds of prehistoric art, including the Venus of Hohle Fels. This appears to be the oldest undisputed example of Upper Paleolithic art and figurative sculpture of the human form in general, from over 35,000 years BP, which was only discovered in 2008; the better-known Venus of Willendorf comes from a little way over the Austrian border. The spectacular finds of Bronze Age golden hats are centred on Germany, as was the central form of Urnfield culture, and Hallstatt culture.

more...