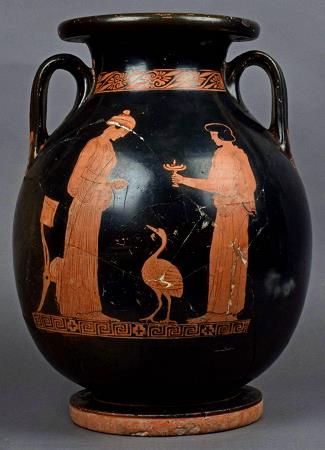

Crane. Cranes are a family, the Gruidae, of large, long-legged, and long-necked birds in the group Gruiformes. The 15 species of cranes are placed in 3 genera, Antigone, Balearica, and Grus. Unlike the similar-looking but unrelated herons, cranes fly with necks outstretched, not pulled back. Cranes live on all continents except Antarctica and South America. They are opportunistic feeders that change their diets according to the season and their own nutrient requirements. They eat a range of items from suitably sized small rodents, fish, amphibians, and insects to grain and berries. Cranes construct platform nests in shallow water, and typically lay two eggs at a time. Both parents help to rear the young, which remain with them until the next breeding season. Some species and populations of cranes migrate over long distances; others do not migrate at all. Cranes are solitary during the breeding season, occurring in pairs, but during the nonbreeding season, they are gregarious, forming large flocks where their numbers are sufficient. Most species of cranes have been affected by human activities and are at the least classified as threatened, if not critically endangered. The plight of the whooping cranes of North America inspired some of the first US legislation to protect endangered species. Cranes are very large birds, often considered the world's tallest flying birds. They range in size from the demoiselle crane, which measures 90 cm in length, to the sarus crane, which can be up to 176 cm, although the heaviest is the red-crowned crane, which can weigh 12 kg prior to migrating. They are long-legged and long-necked birds with streamlined bodies and large, rounded wings. The males and females do not vary in external appearance, but males tend to be slightly larger than females. The plumage of cranes varies by habitat. Species inhabiting vast, open wetlands tend to have more white in their plumage than do species that inhabit smaller wetlands or forested habitats, which tend to be more grey. These white species are also generally larger. The smaller size and colour of the forest species is thought to help them maintain a less conspicuous profile while nesting; two of these species also daub their feathers with mud to further hide while nesting. Most species of cranes have some areas of bare skin on their faces; the only two exceptions are the blue and demoiselle cranes. This skin is used in communication with other cranes, and can be expanded by contracting and relaxing muscles, and change the intensity of colour. Feathers on the head can be moved and erected in the blue, wattled, and demoiselle cranes for signaling, as well. Also important to communication is the position and length of the trachea. In the two crowned cranes, the trachea is shorter and only slightly impressed upon the bone of the sternum, whereas the trachea of the other species is longer and penetrates the sternum. In some species, the entire sternum is fused to the bony plates of the trachea, and this helps amplify the crane's calls, allowing them to carry for several kilometres. The fossil record of cranes leaves much to be desired. Apparently, the subfamilies were well distinct by the Late Eocene. The present genera are apparently some 20 mya old. Biogeography of known fossil and the living taxa of cranes suggests that the group is probably of Old World origin. The extant diversity at the genus level is centered on Africa, making it all the more regrettable that no decent fossil record exists from there. On the other hand, it is peculiar that numerous fossils of Ciconiiformes are documented from there; these birds presumably shared much of their habitat with cranes back then already. Cranes are sister taxa to Eogruidae, a lineage of flightless birds; as predicted by the fossil record of true cranes, eogruids were native to the Old World. A species of true crane, Grus cubensis, has similarly become flightless and ratite-like. The cranes have a cosmopolitan distribution, occurring across most of the world continents. They are absent from Antarctica and, mysteriously, South America. East Asia is the centre of crane diversity, with eight species, followed by Africa, which holds five resident species and wintering populations of a sixth. Australia, Europe, and North America have two regularly occurring species each.

more...