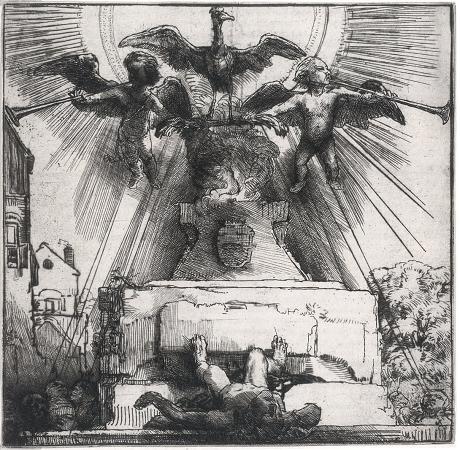

Phoenix. In Ancient Greek folklore, a phoenix is a long-lived bird that cyclically regenerates or is otherwise born again. Associated with the sun, a phoenix obtains new life by arising from the ashes of its predecessor. Some legends say it dies in a show of flames and combustion, others that it simply dies and decomposes before being born again. Most accounts say that it lived for 500 years before rebirth. Herodotus, Lucan, Pliny the Elder, Pope Clement I, Lactantius, Ovid, and Isidore of Seville are among those who have contributed to the retelling and transmission of the phoenix motif. The phoenix symbolized renewal in general, as well as entities and concepts such as the Sun, time, the Roman Empire, Christ, Mary, and virginity. The Greek word is first attested in the Mycenaean Greek po-ni-ke, which probably meant griffin, though it might have meant palm tree. That word is probably a borrowing from a West Semitic word for madder, a red dye made from Rubia tinctorum. The word Phoenician appears to be from the same root, meaning those who work with red dyes. So phoenix may mean the Phoenician bird or the purplish-red bird. The spellings phoenix and phenix are rare nowadays. Classical discourse on the subject of the phoenix points to a potential origin of the phoenix in Ancient Egypt. Herodotus, writing in the 5th century BC, gives a somewhat skeptical account of the phoenix. For example: The Egyptians have also another sacred bird called the phoenix which I myself have never seen, except in pictures. Indeed it is a great rarity, even in Egypt, only coming there once in five hundred years, when the old phoenix dies. Its size and appearance, if it is like the pictures, are as follow: The plumage is partly red, partly golden, while the general make and size are almost exactly that of the eagle. They tell a story of what this bird does, which does not seem to me to be credible: that he comes all the way from Arabia, and brings the parent bird, all plastered over with myrrh, to the temple of the Sun, and there buries the body. In order to bring him, they say, he first forms a ball of myrrh as big as he finds that he can carry; then he hollows out the ball and puts his parent inside, after which he covers over the opening with fresh myrrh, and the ball is then of exactly the same weight as at first; so he brings it to Egypt, plastered over as I have said, and deposits it in the temple of the Sun. Such is the story they tell of the doings of this bird. In the 19th century, scholastic suspicions appeared to be confirmed by the discovery that Egyptians in Heliopolis had venerated the Bennu, a solar bird similar in some respects to the Greek phoenix. However, the Egyptian sources regarding the bennu are often problematic and open to a variety of interpretations. Some of these sources may have actually been influenced by Greek notions of the phoenix, rather than the other way around. The phoenix is sometimes pictured in ancient and medieval literature and medieval art as endowed with a halo, which emphasizes the bird's connection with the Sun. In the oldest images of phoenixes on record these nimbuses often have seven rays, like Helios. Pliny the Elder also describes the bird as having a crest of feathers on its head, and Ezekiel the Dramatist compared it to a rooster. Although the phoenix was generally believed to be colorful and vibrant, sources provide no clear consensus about its coloration. Tacitus says that its color made it stand out from all other birds. Some said that the bird had peacock-like coloring, and Herodotus's claim of the Phoenix being red and yellow is popular in many versions of the story on record. Ezekiel the Dramatist declared that the phoenix had red legs and striking yellow eyes, but Lactantius said that its eyes were blue like sapphires and that its legs were covered in yellow-gold scales with rose-colored talons. Herodotus, Pliny, Solinus, and Philostratus describe the phoenix as similar in size to an eagle, but Lactantius and Ezekiel the Dramatist both claim that the phoenix was larger, with Lactantius declaring that it was even larger than an ostrich. Ideas taking the phoenix into consideration presented themselves in the Gnostic manuscript On the Origin of the World from the Nag Hammadi Library collection: Thus when Sophia Zoe saw that the rulers of darkness had laid a curse upon her counterparts, she was indignant.

more...