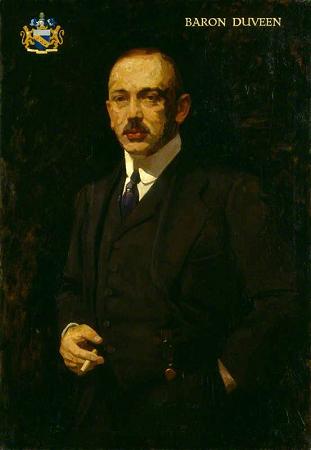

Joseph Duveen (1869 - 1939). Joseph Duveen, 1st Baron Duveen, known as Sir Joseph Duveen, Bt., between 1927 and 1933, was a British art dealer, considered one of the most influential art dealers of all time. Joseph Duveen was British by birth, the eldest of thirteen children of Sir Joseph Joel Duveen, a Dutch-Sephardic Jewish immigrant who had set up a prosperous import business in Hull. The Duveen Brothers firm became very successful and became involved in trading antiques. Duveen Senior died in 1908; Joseph took over the business working in partnership with his late father's brother Henry J. Duveen. He had received a thorough and stimulating education at University College School. He moved the Duveen company into the risky, but lucrative, trade in paintings and quickly became one of the world's leading art dealers due to his good eye, sharpened by his reliance on Bernard Berenson, and skilled salesmanship. His success is famously attributed to noticing that Europe has a great deal of art, and America has a great deal of money. He made his fortune by buying works of art from declining European aristocrats and selling them to the millionaires of the United States. Duveen's clients included Henry Clay Frick, William Randolph Hearst, Henry E. Huntington, J.P. Morgan, Samuel H. Kress, Andrew Mellon, John D. Rockefeller, and a Canadian, Frank Porter Wood. The works that Duveen shipped across the Atlantic remain the core collections of many of the United States' most famous museums. Duveen played an important role in selling to self-made industrialists on the notion that buying art was also buying upper-class status. He greatly expanded the market, especially for Renaissance paintings; with the help of Bernard Berenson, who certified some questionable attributions, but whose ability to put an artistic personality behind paintings helped market them to purchasers whose dim perceptions of art history was as a series of biographies of masters. Duveen quickly became extremely wealthy, and made many philanthropic donations. He gave paintings to many British galleries and he donated considerable sums to repair and expand several galleries and museums. Amongst other things he built the Duveen Gallery of the British Museum to house the Elgin Marbles and a major extension to the Tate Gallery. For his philanthropy he was knighted in 1919, created a Baronet, of Millbank in the City of Westminster, in 1927 and raised to the peerage as Baron Duveen, of Millbank in the City of Westminster, on 3 February 1933. Duveen married Elsie, daughter of Gustav Salomon, of New York, on 31 July 1899. They had one daughter, Dorothy Rose. She married, firstly, Sir William Francis Cuthbert Garthwaite, DSC 2nd Bt., on 23 July 1931, and secondly, in 1938, Bryan Hartop Burns, B.A., B.Ch., F.R.C.S., Orthopedic Surgeon to St. George's Hospital, of Upper Wimpole Street, London. In 1921 Duveen was sued by Andre Hahn for $500,000 following his comments questioning the authenticity of a version of the Leonardo painting La belle ferronniere that she owned and had planned to sell. The court case took seven years to come to trial and after the first jury returned an open verdict, Duveen agreed to settle, paying Hahn $60,000 plus court costs. In recent years, Duveen's reputation has suffered considerably. Restorers working under his guidance damaged Old Master panel paintings by scraping off old varnish and giving the paintings a glossy finish. He was also personally responsible for the damaging restoration work done to the Elgin Marbles. A number of the paintings he sold have turned out to be fakes; it is uncertain whether he knew this when they were sold. Duveen greatly increased the trade in bringing great works of art from Europe to America. He eventually became the art dealer, through shrewd planning and his insight into human behavior. If a great painting came onto the market he had to have it no matter what. He always outbid the opposition and eventually acquired the finest collections. He went to great lengths to purchase great works of art and his network went well beyond American millionaires, English royalty, and art critics. He also relied heavily on valets, maids and butlers of his own household and those of his clients. Because he was capable of making potentially generous payments to top-flight servants, he was often rewarded with information to which other art dealers never had access. One incident from Behrman's biography, Duveen, illustrates this. When Duveen was still a young man in his father's employment, a well-to-do couple came into the store to buy tapestries. As the lady was choosing and picking up pieces generously, Duveen's father discreetly asked him to find out who these people were. Duveen went outside to the horseman and was told that the couple were Mr and Mrs. Guinness.

more...