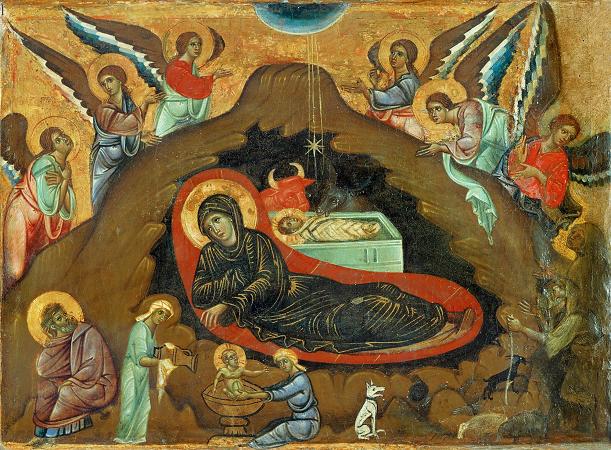

Byzantine Art. Byzantine art refers to the body of Christian Greek artistic products of the Eastern Roman Empire, as well as the nations and states that inherited culturally from the empire. Though the empire itself emerged from the decline of Rome and lasted until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, the start date of the Byzantine period is rather clearer in art history than in political history, if still imprecise. Many Eastern Orthodox states in Eastern Europe, as well as to some degree the Muslim states of the eastern Mediterranean, preserved many aspects of the empire's culture and art for centuries afterward. A number of states contemporary with the Byzantine Empire were culturally influenced by it, without actually being part of it. These included the Rus, as well as some non-Orthodox states like the Republic of Venice, which separated from the Byzantine empire in the 10th century, and the Kingdom of Sicily, which had close ties to the Byzantine Empire and had also been a Byzantine possession until the 10th century with a large Greek-speaking population persisting into the 12th century. Other states having a Byzantine artistic tradition had oscillated throughout the Middle Ages between being part of the Byzantine empire and having periods of independence, such as Serbia and Bulgaria. After the fall of the Byzantine capital of Constantinople in 1453, art produced by Eastern Orthodox Christians living in the Ottoman Empire was often called post-Byzantine. Certain artistic traditions that originated in the Byzantine Empire, particularly in regard to icon painting and church architecture, are maintained in Greece, Cyprus, Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania, Russia and other Eastern Orthodox countries to the present day. Byzantine art originated and evolved from the Christianized Greek culture of the Eastern Roman Empire; content from both Christianity and classical Greek mythology were artistically expressed through Hellenistic modes of style and iconography. The art of Byzantium never lost sight of its classical heritage; the Byzantine capital, Constantinople, was adorned with a large number of classical sculptures, although they eventually became an object of some puzzlement for its inhabitants. The basis of Byzantine art is a fundamental artistic attitude held by the Byzantine Greeks who, like their ancient Greek predecessors, were never satisfied with a play of forms alone, but stimulated by an innate rationalism, endowed forms with life by associating them with a meaningful content. Although the art produced in the Byzantine Empire was marked by periodic revivals of a classical aesthetic, it was above all marked by the development of a new aesthetic defined by its salient abstract, or anti-naturalistic character. If classical art was marked by the attempt to create representations that mimicked reality as closely as possible, Byzantine art seems to have abandoned this attempt in favor of a more symbolic approach. The nature and causes of this transformation, which largely took place during late antiquity, have been a subject of scholarly debate for centuries. Giorgio Vasari attributed it to a decline in artistic skills and standards, which had in turn been revived by his contemporaries in the Italian Renaissance. Although this point of view has been occasionally revived, most notably by Bernard Berenson, modern scholars tend to take a more positive view of the Byzantine aesthetic. Alois Riegl and Josef Strzygowski, writing in the early 20th century, were above all responsible for the revaluation of late antique art. Riegl saw it as a natural development of pre-existing tendencies in Roman art, whereas Strzygowski viewed it as a product of oriental influences. Notable recent contributions to the debate include those of Ernst Kitzinger, who traced a dialectic between abstract and Hellenistic tendencies in late antiquity, and John Onians, who saw an increase in visual response in late antiquity, through which a viewer could look at something which was in twentieth-century terms purely abstract and find it representational. In any case, the debate is purely modern: it is clear that most Byzantine viewers did not consider their art to be abstract or unnaturalistic. As Cyril Mango has observed, our own appreciation of Byzantine art stems largely from the fact that this art is not naturalistic; yet the Byzantines themselves, judging by their extant statements, regarded it as being highly naturalistic and as being directly in the tradition of Phidias, Apelles, and Zeuxis.

more...