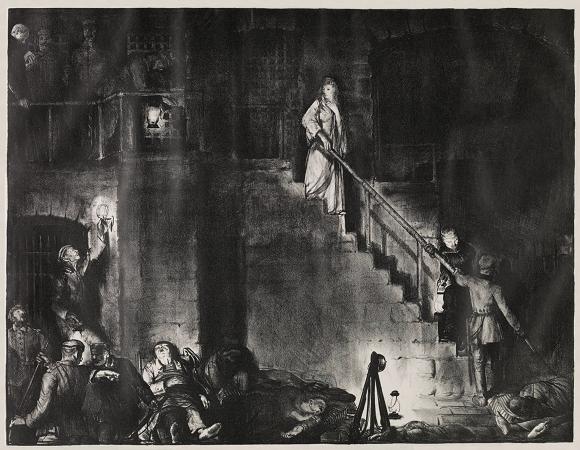

Murder of Edith Cavell (1918). Lithograph. 48 x 63. Edith Louisa Cavell was a British nurse. She is celebrated for saving the lives of soldiers from both sides without discrimination and in helping some 200 Triple Entente soldiers escape from German-occupied Belgium during the First World War, for which she was arrested. She was accused of treason, found guilty by a court-martial and sentenced to death. Despite international pressure for mercy, she was shot by a German firing squad. Her execution received worldwide condemnation and extensive press coverage. The night before her execution, she said, Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone. These words were later inscribed on a memorial to her near Trafalgar Square. Her strong Anglican beliefs propelled her to help all those who needed it, both German and Allied soldiers. She was quoted as saying, I can't stop while there are lives to be saved. The Church of England commemorates her in its Calendar of Saints on 12 October. Cavell, who was 49 at the time of her execution, was already notable as a pioneer of modern nursing in Belgium. Cavell was born on 4 December 1865 in Swardeston, a village near Norwich, where her father was vicar for 45 years. She was the eldest of the four children of the Reverend Frederick Cavell and his wife Louisa Sophia Warming. Edith's siblings were; Florence Mary, Mary Lilian and John Frederick S. She was educated at Norwich High School for Girls, then boarding schools in Clevedon, Somerset and Peterborough. After a period as a governess, including for a family in Brussels from 1890 to 1895, she returned home to care for her father during a serious illness. The experience led her to become a nurse after her father's recovery. In April 1896, at the age of 30, Cavell applied to become a nurse probationer at the London Hospital under Matron Eva Luckes. She worked in various hospitals in England, including Shoreditch Infirmary. As a private travelling nurse treating patients in their homes, Cavell travelled to tend patients with cancer, gout, pneumonia, pleurisy, eye issues and appendicitis. In 1907, Cavell was recruited by Dr Antoine Depage to be matron of a newly established nursing school, L'Ecole Belge d'Infirmieres Diplomees on the Rue de la Culture, in Ixelles, Brussels. By 1910, Miss Cavell 'felt that the profession of nursing had gained sufficient foothold in Belgium to warrant the publishing of a professional journal' and, therefore, launched the nursing journal, L'infirmiere. Within a year, she was training nurses for three hospitals, twenty-four schools, and thirteen kindergartens in Belgium. When the First World War broke out, she was visiting her widowed mother in Norfolk. She returned to Brussels, where her clinic and nursing school were taken over by the Red Cross. Cavell had been offered a position as matron in a Brussels clinic. She worked closely with Dr Depage who was part of a growing body of people in the medical profession in Belgium. He realised that the care that was being provided by the religious institutions had not been keeping up with medical advances. In 1910 Cavell was asked if she would be the matron for the new secular hospital at St Gilles. In November 1914, after the German occupation of Brussels, Cavell began sheltering British soldiers and funnelling them out of occupied Belgium to the neutral Netherlands. Wounded British and French soldiers as well as Belgian and French civilians of military age were hidden from the Germans and provided with false papers by Prince Reginald de Croi at his chateau of Bellignies near Mons. From there, they were conducted by various guides to the houses of Cavell, Louis Severin, and others in Brussels, where their hosts would furnish them with money to reach the Dutch frontier, and provide them with guides obtained through Philippe Baucq. This placed Cavell in violation of German military law. German authorities became increasingly suspicious of the nurse's actions, which were further fuelled by her outspokenness. She was arrested on 3 August 1915 and charged with harbouring Allied soldiers. She had been betrayed by Gaston Quien, who was later convicted by a French court as a collaborator. She was held in Saint-Gilles prison for ten weeks, the last two of which were spent in solitary confinement. She made three depositions to the German police, admitting that she had been instrumental in conveying about 60 British and 15 French soldiers, as well as about 100 French and Belgian civilians of military age, to the frontier and had sheltered most of them in her house. In her court-martial she was prosecuted for aiding British and French soldiers, in addition to young Belgian men, to cross the Dutch border and eventually enter Britain.

more...